Mississippi ‘throws away’ juveniles, robbing them of chance for redemption, advocates say

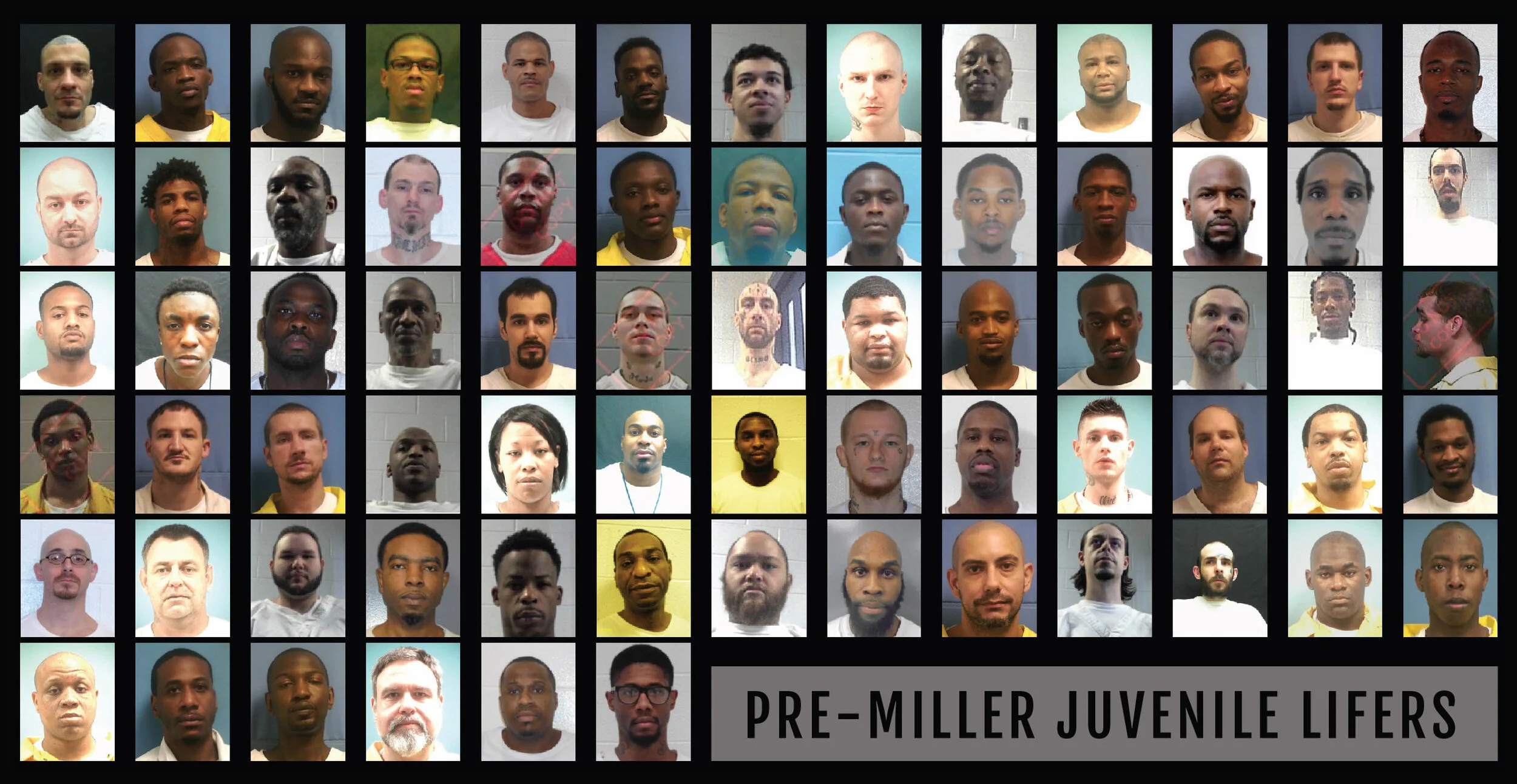

These inmates were automatically sentenced to life without parole for a homicide they committed before they were 18. In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court said such mandatory sentences for juveniles are unconstitutional, entitling them to a new sentencing hearing. Some have since been resentenced to life with parole. The Mississippi Department of Corrections reported this summer that 13 were paroled (photos not shown). Contributors: Asia Allen and Magill Grunfeld. Graphic: Katherine Mitchell. Source: MDOC

By Shirley L. Smith

Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting

Despite a nationwide trend to abolish life-without-parole sentences for minors, Mississippi continues to violate the Constitution by condemning juveniles convicted of homicide to die in prison even if they show potential to change, juvenile justice advocates said.

“Some judges in Mississippi are going through the motions of holding a hearing, but aren't asking or answering the essential question of whether the juvenile is capable of rehabilitation,” said Jacob Howard, legal director of the MacArthur Justice Center in Mississippi. “As a result, numerous juvenile offenders who have demonstrated the capacity for rehabilitation have been unconstitutionally sentenced to life without parole, and these decisions are being rubber-stamped by the state’s appellate courts.”

Stacy Ferraro, a former juvenile parole resource counsel for the Mississippi Office of State Public Defender, echoed Howard’s sentiments. “When they were 15, 16 and 17, some of them 14, the state made a decision that we will throw you away forever — and the taxpayers will pay for you forever — for a crime they committed when they were teenagers. And they were put in this violent, dangerous environment where the water is moldy and the toilets don’t flush and (that) is run by gangs.”

On Nov. 3, Mississippi’s sentencing practices will be under the microscope of the U.S. Supreme Court when it hears arguments in the appeal of Brett Jones, who was convicted of murdering his paternal grandfather when he was 15. Howard, one of Jones’ lawyers, said the now 31-year-old was unconstitutionally sentenced to life without parole — twice.

Jones’ case requires the high court to revisit two landmark rulings intended to shield juveniles, even those that commit heinous crimes, from being sentenced to life in prison without any possibility of parole except in cases where they are beyond redemption. The outcome of the case is expected to have national implications.

Between 2005 and 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court forced Mississippi and the nation to reevaluate how they treat juvenile offenders.

In 2005, the court struck down the death penalty for children in Roper v. Simmons. At the time, five juvenile offenders in Mississippi were on death row, said André de Gruy, the state’s public defender. In 2010, in Graham v. Florida, the court banned life-without-parole sentences for juveniles convicted of nonhomicide crimes. Then, in 2012, in Miller v. Alabama, it banned mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles who committed a homicide before they were 18. Four years later, the court ruled in Montgomery v. Louisiana that Miller should be applied retroactively.

These decisions have led to reforms in the sentencing of youth across the country, but ambiguities in the Miller and Montgomery rulings have caused confusion in the lower courts, leading to extensive litigation. And while hundreds of juvenile offenders destined to die in prison have become eligible for parole or been released, their journey has been an agonizing, emotional rollercoaster for their victims’ families, who have had to relive the murders of their loved ones at resentencing and parole hearings.

Victims’ families deserve legal finality so they can move on with their lives, said Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins, founder and acting president of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Murderers.

After the Miller and Montgomery rulings, Bishop-Jenkins, a resident of Illinois, said she received hundreds of calls from victims’ families who thought their cases were closed, only to find out they would be reopened and they would have to re-engage with the killer of their loved ones at resentencing hearings and repeated parole hearings. “That is torture,” she said.

“The court has to take that into account. It’s not just about the killers. It’s also about the trauma left behind in the wake of these devastating crimes,” Bishop-Jenkins said. Her sister, brother-in-law and their unborn child were murdered in Winnetka, Illinois, by a teenager, who “lived in a wealthy suburb” and came from “a great family.” Though this tragedy occurred 30 years ago, her emotions are raw. “Whenever I get close to thinking about this murder, this loss in my life, my heart races. I am already shaking. My throat is tight.”

Mississippi’s Parole Board meets with victims’ families before parole hearings, so they do not have to interact with the perpetrator, board Chairman Steven Pickett said. The hearings are conducted remotely, with the inmates attending via video from the prison. However, if family members choose to attend a resentencing hearing, they would have to re-engage with the murderer.

The Supreme Court’s Miller decision did not ban all life-without-parole sentences for juveniles, but it held that mandatory life-without-parole sentences are unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits “cruel and unusual punishment.”

The court said juveniles facing a lifetime in prison are entitled to an “individualized” sentencing hearing that considers their age, the circumstances of the crime and their participation, their family and home environment, their ability to deal with law enforcement and prosecutors and assist their attorney, and the possibility of rehabilitation.

“A state is not required to guarantee eventual freedom but must provide some meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation,” the court said. The court also emphasized that a life-without-parole sentence should be reserved for the “rare” juvenile who is “permanently incorrigible” and cannot be rehabilitated.

Permanent incorrigibility is at the heart of Jones’ case. His attorneys are asking the U.S. Supreme Court to make a definitive ruling on whether a judge or jury must determine if a juvenile offender is permanently incorrigible before imposing a life-without-parole sentence.

Howard insists such a finding is required, but the Mississippi Supreme Court has held that all a judge or jury has to do is consider the offender’s age at the time of the crime and other mitigating factors described in Miller.

Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens II agreed with Howard that the state Supreme Court’s interpretation of Miller is inaccurate, and Mississippi is not living up to the spirit of the Miller and Montgomery decisions.

When Montgomery was decided in 2016, about 2,400 people in the U.S. were serving mandatory life-without-parole sentences for a homicide they committed when they were under the age of 18, said Heather Renwick, legal director for The Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth.

The Miller and Montgomery rulings gave these so-called “juvenile lifers” the legal right to have a new hearing to determine whether their sentences were appropriate or they should have an opportunity for parole in the future. Some jurisdictions forego the costly hearing process if the prosecutor and the juvenile offender can agree on a parole-eligible sentence.

"Since Miller, about 650 of these juvenile lifers have been released as a result of judicial resentencing hearings or state legislative reforms," Renwick said. But eight years later, hundreds of juvenile lifers are still waiting for their sentences to be reviewed.

Jones is one of 87 juvenile lifers who were serving mandatory life-without-parole sentences in Mississippi before the Miller decision, de Gruy said. Of those, one died in custody, one was acquitted after a retrial and one pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of manslaughter. Though Jones is white, 71 percent of Mississippi’s juvenile lifers are Black.

Before Owens was elected in August 2019, he was the managing attorney for the Mississippi office of the Southern Poverty Law Center where he was lead counsel for many of these juvenile lifers and assisted them with getting their resentencing hearing.

Jones had his new hearing in 2015, but his attorneys said the judge resentenced him to life without parole “without meaningfully considering his positive growth and change as required by the Court in Miller and without determining that Brett is ‘permanently incorrigible.’”

In support of Jones’ appeal, several current and former federal, state and local prosecutors, Department of Justice officials, and judges said in a joint brief: “The trial court’s handling of Brett’s resentencing in this case, and its approval by the Mississippi Supreme Court over the vigorous dissent of four justices, fail to effectuate this Court’s mandate and undermine confidence in the fairness of the criminal justice system.”

Mississippi’s attorney general’s office, which is representing the state in Jones’ case, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. However, the state maintains in its opposition to Jones’ appeal that he “received precisely what the Eighth Amendment requires: an individualized sentencing hearing where the sentencing judge considered youth and its attendant characteristics before imposing a life without parole sentence.”

Families of juvenile lifers and other inmates in Mississippi attend a Prayer for Prisons Rally on Jan. 23, 2020, at the state Capitol to plead for a second chance for their loved ones. Cathy McOmber, a criminal justice advocate for inmates in Mississippi, and Pastor Rickey Scott organized the rally. Asia Allen/MCIR

The U.S. Supreme Court decisions were based on scientific evidence that children’s brains are developmentally different from adults; something the justices said, “any parent knows.” The court reasoned that children are less culpable for crimes because of their lack of maturity, vulnerability to negative influences from family and peers, their limited control over their environment, and the fact that they “lack the ability to extricate themselves from horrific, crime-producing settings.”

Unlike the perpetrator in Bishop-Jenkins’ case, many of the juvenile lifers in Mississippi are from impoverished families and experienced abuse or neglect, and many grew up in high-crime areas, Howard said. “Some have intellectual disabilities. Some have mental health issues.”

Many of them were dependent on the state’s judicially controlled, poorly funded public defender system for representation. “The state has 82 counties, but only seven counties have a full-time public defender office,” Howard said.

Across the Southeast, de Gruy said, “every state has either a state-funded or state oversight public defender system. Mississippi is the only one that has neither.”

Mississippi has a county-based public defender system that operates independently from the state and is funded by the counties, many of which have scarce resources.

In a few counties, de Gruy said, “judges appoint lawyers to handle individual cases but the vast majority of counties contract with private attorneys, also selected by judges, to handle an unlimited number of cases.”

Although de Gruy’s office is responsible for training public defenders in the state, it is only authorized to handle death penalty cases, criminal appeals for indigent individuals convicted of a felony and limited matters from Youth Court.

Some of the juveniles sentenced to life without parole did not kill anyone. Under Mississippi’s capital murder statute, Howard said individuals who participate in certain crimes are as guilty as the person who commits the crime. For instance, if a juvenile drove the getaway car to a robbery where someone was killed, that juvenile can get the same life-without-parole sentence as the person who pulled the trigger even if he never got out of the car, he said.

To look at these juvenile lifers now as fully grown adults, some with prison tattoos, it is easy to forget that they were locked up when they were children, Ferraro said. “The sadness is, they were all children, and they were raised by the Mississippi Department of Corrections. Some of them have done amazingly well, but they have all been damaged by that experience.”

Since Miller was decided in 2012, Renwick said Democratic- and Republican-controlled state legislatures in 23 states and the District of Columbia have banned life-without-parole sentences for juveniles in favor of age-appropriate penalties that hold them accountable but offer an opportunity for release. Six other states do not have any juveniles serving life-without-parole sentences even though it is permissible.

“The fact that it's still a statutorily available penalty (for juveniles) in Mississippi means that the state is not keeping up with national sentencing trends,” Renwick said.

Prosecutors and defense attorneys alike say legislators in Mississippi need to revise the state’s sentencing and parole laws to bring them into compliance with Miller, although some prosecutors oppose abolishing life without parole.

In the absence of legislative action, the Mississippi Supreme Court has developed a stopgap measure that allows prosecutors to offer two sentencing options to juveniles convicted of first-degree murder and capital murder – life without parole after an individualized sentencing hearing or life with parole eligibility after serving 10 years.

Lee County District Attorney John Weddle, who urged the court to resentence Jones to life without parole, said prosecutors need more flexibility for these serious crimes.

“There's such a gap between 10-year eligibility for parole and then no eligibility for parole,” Weddle said. “I think 10 years is too early to be considered for parole. I mean you've got some people that go to prison for an armed robbery and get 40 years and they're not eligible for parole until after they serve 20 years. I wish we had something that would make eligibility a little bit farther down the road than 10 years.”

Owens said prosecutors generally understand that Mississippi’s Parole Board will not release anyone convicted of murder after serving just 10 years. Still, he said, “I think because of the nature of the crime many prosecutors feel that they have to (give) the max time allowable under the law."

Sen. Juan Barnett, chairman of Mississippi’s Senate Corrections Committee and a champion of criminal justice reform, said more legislators from both parties are realizing “this lock them up and throw away the key mentality has to change.”

Barnett knows too well the anguish of losing a loved one to violence. When he was serving his country in Iraq in 1990, his father was murdered. “It’s something that I have to deal with daily,” he said. Nevertheless, Barnett believes in second chances and in the power of forgiveness. He said people who make an effort to rehabilitate themselves, especially juveniles from troubled backgrounds, should be given a chance to become productive citizens.

“We put (people) in a place where they are just lost forever, and I just think we just got to give individuals hope,” he said. “If you are only going to lock someone up and never give them the opportunity to redeem themselves, then what kind of environment are we creating? We just can’t keep throwing money, taxpayers dollars away, and not let some of these individuals come out, because if you look through history, you will find that there are a lot of individuals who committed crimes and are very successful now.”

‘Justice by geography is very real’

Fifty-six juvenile lifers have been resentenced to date in Mississippi, de Gruy said. Forty were resentenced to life with parole eligibility after serving 10 years, and 16 (or 29 percent) were resentenced to life without parole. “This is not rare,” de Gruy said. One of the life without parole sentences has been reversed due to ineffective assistance of counsel, and the juvenile is awaiting resentencing. The lives of 28 juvenile lifers remain in limbo, as they anxiously look forward to their long-awaited resentencing hearing.

By contrast, Pennsylvania, which had the largest number of juvenile lifers before Miller, has resentenced five of its 521 juvenile lifers to life without parole, said Marsha Levick, chief legal officer of the Juvenile Law Center. The national youth advocacy organization tracks data related to juveniles in the justice system.

Data from Mississippi’s state public defender office also show that post-Miller, 12 juveniles have been convicted of first-degree murder or capital murder. Eight of them were sentenced to life without parole. One was reversed on appeal and the juvenile was resentenced to life with parole.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court’s rulings were intended to protect children’s constitutional rights, advocates said ambiguities in the Miller and Montgomery rulings have in some ways undermined the court’s intention.

The high court did not establish any specific procedure for the resentencing and sentencing hearings, nor did it specify how the judge should determine if a juvenile offender is permanently incorrigible. So, each state had to figure out how to implement the court’s mandate, and judges were left with the “extraordinarily difficult” task of predicting a juvenile offender’s future danger to society or “inability to change for the better,” Renwick said.

“The procedure that exists in Mississippi is that we trust the moral judgment of the judge. He listens to the petition and just decides what he thinks is right,” de Gruy said. “This does not appear to be working when 29 percent of the people being resentenced are receiving the punishment that is supposed to be rare.”

The Supreme Court’s lack of clarity has not only led to different interpretations of Miller and Montgomery by the states but inconsistencies in sentencing across the country and within a state, Renwick said. She said a juvenile offender’s fate is not just dependent on the facts of the crime and the individual’s ability for rehabilitation, but what state and county the individual lives in and the judge who presides over the sentencing or resentencing hearing.

An analysis of resentencings in the state by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting revealed that five of the seven juvenile lifers who have had their resentencing hearings in Jackson County were resentenced to life without parole, whereas, all of the 11 juvenile lifers resentenced in Hinds County were given life with parole.

“Justice by geography is very real and how people view sentencing of kids is very different in all jurisdictions. In Hinds County, we prioritize treating children differently, because they are different. I think my predecessor certainly recognized that and I do, too,” Owens said. All but one of the resentencing occurred before Owens’ tenure.

Owens said juveniles convicted of violent crimes should be held accountable, “but it’s clear that their understanding and appreciation of what they did as kids is not the same as that of an adult, and as such, we shouldn’t punish them the same way we would an adult.”

Court records show the Jackson County judges considered the “Miller factors” and that most of the five juvenile lifers denied parole eligibility had planned the murders they committed. However, Ferraro said, "in each case, the judge failed to apply the proper standard.” Either the judge did not determine the juvenile offender was permanently incorrigible before reimposing life without parole or the judge incorrectly focused on the crime and ignored evidence demonstrating a capacity for rehabilitation when erroneously concluding the offender was permanently incorrigible, she said.

In one court order, Jackson County Judge Dale Harkey said: “With the Miller ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court crafted an almost-impossible standard rooted in ever-vacillating psychological constructs.”

Advocates said the disparities in sentencing will continue as long as there is no uniform procedure and no clear judicial or legislative guidance. Additionally, they said, unless the state abolishes life-without-parole sentences for juveniles, those capable of rehabilitation will continue to be at risk for being unconstitutionally sentenced to die in prison.

This project was produced in partnership with the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Report for America corps member Shirley L. Smith is an investigative reporter for the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization that seeks to inform, educate and empower Mississippians in their communities through the use of investigative journalism. Sign up for our newsletter.

Report for America is an initiative of, and supported by, its parent Section 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization The GroundTruth Project (EIN: 46-0908502).