Elected coroners lacking needed medical training make life and death decisions

Scott County, Kentucky, is like many counties in America that rely on elected coroners who have to meet few requirements, and little or no medical training, to serve. Emma Keady/University of Missouri and MCIR

By Emma Keady and Teghan Simonton

From the University of Missouri School of Journalism Investigative Reporting Project in collaboration with MCIR

SCOTT COUNTY, Kentucky – Storing guns stolen from police headquarters in the basement of his government building.

Stealing drugs from death scenes.

Falsifying death records.

Using a county vehicle to transport moonshine — and human eyeballs.

Sorry crime-thriller junkies, this is not a teaser for the newest Netflix original.

Rather, these are all allegations against John Goble, the coroner of this suburban county, many of which were contained in state and federal indictments handed down earlier this year.

But none of them stopped Goble — serving his 20th year in office – from continuing in his capacity as the ultimate authority on why and how residents of this central Kentucky county die.

In Kentucky, a coroner is the highest elected law enforcement official in the county. Yet, the requirements for the position are minimal: a high school degree and being at least 24 years old.

Coroners answer to the people who elect them but more times than not, the majority of voters have no idea who they are and how powerful they are under a system that gives them expansive authority over questions of life and death.

Lana Pennington, a volunteer deputy coroner of Scott County, worked for Goble and is now running to replace him. She concedes that the system has flaws.

“There’s no accountability,” Pennington said.

A Medieval Legacy

America’s coroner system is deeply flawed. Many states have structures like Scott County, where someone can be elected with little to no expertise or training. The results are often as predictable as they are devastating: botched investigations, wrongful arrests and convictions and, in some cases, exoneration of criminals freed through sloppy, biased or corrupt probes.

In some California counties, the sheriff also serves as coroner – with no special requirements. That means that in death investigations involving law enforcement officers, the person making the final call often not only has limited or no expertise but possibly a vested interest in the outcome.

In 2020 in one Colorado county, the man entrusted with determining suspicious or unresolved deaths ran funeral homes that were raided by the FBI following multiple complaints involving the mishandling of human remains. Among the findings: unrefrigerated bodies and a baby’s corpse stored in a casket.

A Georgia coroner’s testimony in 2015 helped convict a mother who had lost her baby because he told jurors that her reaction “was not how a grieving mother sounds,” according to a former prosecutor who now regrets using the testimony.

And in Scott County, a bedroom community north of Lexington of about 60,000 residents, assistants in the office said Goble often ruled the causes of deaths to be heart attacks – because no matter what else might have caused a death, the heart stopped beating.

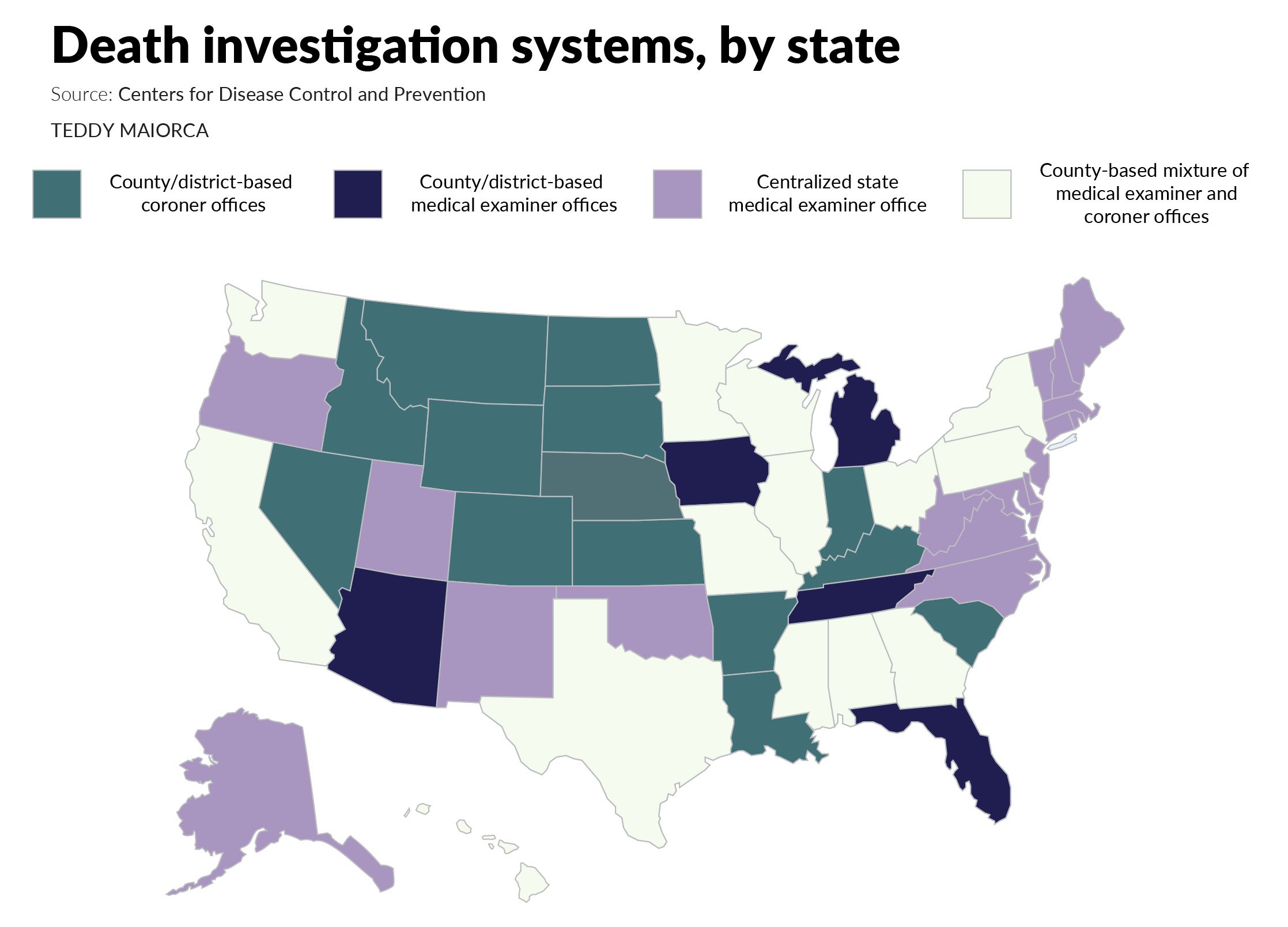

Nationwide, there are generally two options for handling death investigations: medical examiners, who by law must have specific training and in some cases medical degrees, or coroners, whose training often is limited to short courses they are required to take once they are elected. In many states, the system varies by county, with coroners handling cases in small or rural locales where recruiting someone with medical expertise is difficult.

The coroner system dates back to medieval times when the job was to determine how and when people died in order to collect taxes. A movement to replace the system rose up in the 1960s and ‘70s when several states converted to a medical examiner system. A 2009 report by the National Academy of Sciences recommended abolishing the position of coroners and establishing new offices run by medical examiners, with national standards for accreditation.

But the movement foundered on a demographic reality: the increasing shortage of physicians and medical services in rural areas. According to the National Rural Health Association, there are 13 doctors for every 10,000 rural residents in the U.S.; in urban areas there are 30. “It is irrational to think that the U.S. could ever completely abolish the coroner system,” said Kathryn Pinneri, president of the National Association of Medical Examiners. “The best thing to do is to make whatever system exists the best it can be.”

California: The ‘Nature of the Beast’

In California, 48 of 58 counties use combination sheriff-coroners, a position that melds the head law enforcement official with the ultimate authority in autopsies.

The state legislature tried to change the system in 2018, when both chambers passed a bill to establish medical examiner’s offices in every county with a population over 500,000. But it was ultimately vetoed by then-Gov. Jerry Brown. In his veto message, he said the decision to reform the system should be up to local elected officials.

But the arrangement has sometimes caused tension – particularly when deaths occur in police custody.

The sheriff-coroner position is “ripe for conflict,” said David Cohn, an attorney in Kern County, Ca. “How can anyone claim this is truly objective?”

Cohn in 2013 represented the family of David Silva, who died in a struggle with police. His cause of death was listed as “excited delirium,” a cause once common among deaths by law enforcement when drugs were involved.

Silva had been using methamphetamines at the time. But Cohn argued a number of the officers’ actions were aggressive and unethical: he said Silva was hobbled and that officers collected onlookers’ cell phones, which Cohn believes allowed police to conceal evidence of possible misconduct. Council for the county later claimed authorities were justified in securing the phones because they were evidence in an in-custody death, according to past news coverage.

Cohn said the coroner report seemed to be heavily predicated on what police investigators had told the pathologist. In other words, the report was influenced by the officers’ narrative. The case was ultimately settled with a payout of $3.4 million to Silva’s family — though officials maintained that officers handled the situation appropriately. But the “excited delirium” cause of death has been called baseless by independent research, with “racist and unscientific origins,” according to Physicians for Human Rights, an activist group, in a report the organization filed in March 2022.

California is one of only three states that uses sheriff-coroners. Cases like Silva’s have emerged repeatedly, and there have been numerous attempts in the state legislature to separate the sheriff and coroner offices.

The 2018 bill had been inspired by a high-profile scandal in San Joaquin County, California. Two pathologists resigned from the coroner’s office in 2017 after accusing the sheriff-coroner, Steve Moore, of interfering with their work. Their deluge of allegations included intentionally delaying autopsies for homicides, misidentifying manner of death, bullying of staff and more.

“When law enforcement has the ability to assert any level of control or influence over the practice of forensic medicine, we as physicians are failing not only our community, but also our pledge of the Hippocratic Oath and professional ethical standards and practice.” The statement came from Dr. Susan Parson, one of the pathologists, in a 54-page memo released after her resignation.

Dr. Bennet Omalu, the chief medical examiner, resigned two days after Parson. Describing one case of a death that occurred in an altercation with police, Omalu alleged Moore asked him to modify the autopsy report. Omalu refused, and said he later learned changes were made to the coroner’s report without the advice of any pathologist in the office.

“I became frigidly afraid that in continuing to work under the circumstances Sheriff Steve Moore has created in his office, that I may be aiding and abetting the unlicensed practice of medicine,” Omalu wrote in his resignation letter.

Later, an independent audit reviewed five cases where the deceased died in police custody, and found that in several of the cases, the cause of death identified by the pathologist did not match the coroner’s final report. The pathologist would rule the death a homicide, but the coroner would certify the manner of death as an accident.

Moore denied all the allegations and later retired. He couldn’t be reached for comment. But the scandal still led the county’s Board of Supervisors to abolish the sheriff-coroner system altogether, separating the offices and establishing an independent medical examiner office in a unanimous vote in April 2018.

Absent a state law change, Cohn hopes the citizens of Kern County will one day vote to separate the offices. But even that wouldn’t solve everything.

“Let’s not be naïve,” he said. “When the coroner’s office was separate, did they work hand in hand with the law enforcement agencies? Of course they did.”

Even with an independent coroner and independent law enforcement, there will be a “closeness,” Cohn said, because of how often the two work together. He said that’s why attorneys so often order second autopsies by private pathologists.

Cohn doubts a perfect system exists.

“As long as the coroner is going to be a public official tied to the government, working closely with law enforcement,” he said, “you’re always going to have a conflict. It’s just the nature of the beast.”

Guns, Ammo And Moonshine

In the heart of Scott County, Kentucky, government buildings line Main Street in the small town of Georgetown. On one red brick building, the windows framing the front door read, “Scott County Coroner,” and for about 20 years, underneath was the name “John P. Goble.”

The community in Georgetown knew Goble’s name long before it was displayed on those windows. Goble did not venture far from his birthplace after attending Scott County High School and Eastern Kentucky University. He served in the U.S. Marine Corps before beginning his 20 years as an officer of the Kentucky State Police, where he spent most of his career as a state trooper. He made his debut in local politics in 2001, when he was elected to the Georgetown City Council. After a two-year term, he returned to the law enforcement arena and won the Scott County coroner election in 2002.

Goble is a popular man in the small town, with nearly 5,000 Facebook friends. But he received unwanted attention in 2018 when he was criminally indicted in state and federal courts on seven counts, including receiving stolen property, abuse of public trust and possession of a controlled substance.

The Scott County coroner's office sat empty most days in the latter days of Goble’s time in office. According to staff, there was no formal on-call schedule for the office. Deputies and volunteers waited for a call from Goble, headed over to a scene to conduct their work and then handed off their material to Goble, who independently produced death certificates and accompanying paperwork.

In 2017, three former coroner deputies who had worked under Goble sued him for retaliation after they told officials that they’d seen him take drugs from a death scene, allegations mirrored in an indictment that says Goble was in illegal possession of 90 tablets of Oxycodone.

In their lawsuit, filed in Scott County Circuit Court, they alleged that Goble would label most causes of death as heart attacks as a way to reduce paperwork.

Goble’s legal troubles centered in part on allegations that he stored more than $40,000 in ammunition, three M1A rifles and 10 Remington shotguns that had been illegally obtained from Kentucky State Police, according to an indictment in U.S. District Court.

The property was obtained through falsified money orders for the guns and ammunition from the Kentucky State Police supply office using the name of a Kentucky State Police officer, according to court records.

Goble told investigators he was unaware of the unlawful nature of the weapons and ammo. He said he thought he was simply doing a favor for the commander of the supply office.

But investigators were led to believe Goble knew differently. In an interview with investigators he gave in 2018 he had told them a story of when he worked for the state police and got his lieutenant a $300 jacket normally reserved for members of the troopers’ “special reaction team.” He said he had a connection and that as state policemen, “we did what we wanted.”

After investigators began looking into the stolen property in November 2017, the ammunition disappeared from the office basement and was placed in the home of a man who began receiving $500 monthly checks as a deputy coroner, even though investigators determined he performed no duties for the office, according to court records in the case.

Investigators also alleged Goble was misusing state vehicles. According to a grand jury indictment of Goble, he profited from using a county vehicle to transport and make deliveries from the Kentucky Eye Bank. He and the eye bank have said that Goble was not paid. He also had a side business selling moonshine — legal in Kentucky. Investigators determined he was using the coroner’s vehicle to transport the liquor.

All this time, and through four years of legal wrangling, Goble continued as coroner.

‘I Just Wanted My Baby’s Ashes’

Shannon Kent’s funeral homes in Colorado had an abhorrent record.

Sheriff’s investigators, acting on complaints, found unrefrigerated bodies, unlabeled remains and an abandoned still-born infant. A lawsuit filed in Eagle County District Court in 2020 claimed parents whose stillborn babies were supposed to be cremated were given the wrong remains.

But until he resigned last year facing more charges, Kent was the longtime coroner for Lake County.

“I was a grieving mother and I just wanted my baby's ashes,” said Chantal Reh, a mother from Avon, Colorado, who gave birth to a stillborn daughter in 2018 and was recommended to Kent by the hospital.

After a series of delays, Reh came to the conclusion she was given the wrong urn filled with ashes that came with no identifying paperwork. Her case mirrored that of another family who had the same results from the funeral home.

Kent also had legal trouble in his role as coroner, being convicted in district court in September 2021 for sending his wife, Staci, out on calls despite the fact she was not part of the coroner’s office.

Randy Keller, president of the Colorado Coroners Association, said each county elects a coroner who is required to undergo 40 hours of association training and take yearly refresher courses. But there are little to no background requirements to run for office and no official regulatory body to oversee county coroners. Coroners and funeral directors would only be inspected if “complaints were filed by the public,” he said.

The Kent case is “particularly challenging because not only does Mr. Kent run the funeral homes in the area and the crematory, but he's also the elected coroner," said Karen McGovern, Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies deputy director of legal affairs.

Keller said that “oftentimes in these rural counties, the coroner also owns the funeral home, because they’re the only ones in the community comfortable around corpses.”

Kent, according to documents filed in state court, now faces 14 criminal charges including four felony counts of abuse of a corpse; one misdemeanor count of abuse of a corpse; two counts of unlawful acts related to cremation; one count of first-degree official misconduct; two counts of second-degree official misconduct; three counts of falsifying health information; and one count of unlawful acts related to a mortuary.

He and his wife were acquitted in June in a case involving an unrefrigerated body and charges of corpse abuse, with jurors determining they’d done all they could in that instance. Kent declined to comment for this story but he told local media, in an interview on June 8, “We have maintained our honesty throughout all of this process and will continue to do so.”

Shannon Kent was convicted in September of second-degree official misconduct related to sending his wife out on death calls. Staci Kent reached a plea deal on the same charge.Both were sentenced to six months unsupervised probation.

Former Lake County, Colo., coroner Shannon Kent, left, was convicted in September of second-degree official misconduct for sending his wife, Staci Kent, to several death scenes despite her not being a deputy coroner. Staci Kent reached a plea deal on the same charge. Photo courtesy of Summitt County, Colo., Sheriff's Office

That lack of regulation plays out in similar ways across the country.

In Howard County, Missouri, the case of Jayke Minor was almost enough to lead to reform in the coroner system.

Minor’s suspicious death in 2011 was initially ruled a drug overdose by a county coroner, based on no evidence other than information that Minor, 27, had been a drug user. Ultimately, a much-delayed toxicology report conducted by the Missouri State Highway Patrol proved that was impossible — the only drug Minor had in his system was marijuana. The ruling was changed to cardiac dysrhythmia; basically his heart stopped.

There were other red flags. According to previous reporting comparing various official documents, the death report initially had someone else’s name on it and had several key details of the death scene wrong, including the location and temperature of the body. But because Minor had been cremated, no further investigation was possible. And no autopsy was performed, apparently to save money.

“Not to do an autopsy on somebody that age when you don't have a clear cause of death, it's just insane,” said Bob Smith, coroner of another Missouri county who was brought in by Minor’s family to try to get answers about his case.

Jay Minor, who has fought unsuccessfully for years to learn the truth about how his son died, testified at legislative hearings for a bill that would have created new standards for Missouri coroners. The bill was approved in 2019 and sent to Gov. Michael Parsons, who vetoed it because it contained an odd provision to allow open-air “Viking” style funerals. The governor said he felt the provision might allow disposal of loved ones’ remains in a manner not keeping with “utmost care and respect.”

Lawmakers tried again the next year, and a Coroner Standards and Training Commission was approved. However, two years later, it has yet to meet because the governor has been slow to appoint enough members to fill a quorum on the eight-person board. The board now has five members.

Jayke Minor left behind three children who will never know why their father died.

“I knew at some point they were going to ask me what happened. I didn't have that answer,” Jay Minor said. “How do you, how do you tell a kid, I don't know what happened to your daddy?”

Jay Minor has fought for years to determine how his son died after a faulty ruling by a coroner in Missouri blamed a drug overdose.Credit: KOMU-TV

‘Not a Murder Case At All’

A Georgia case echoes how the coroner’s system produces rulings that spur controversy and lead to accusations of wrongful convictions.

An 18-year-old man was given a life sentence for murdering his friend following a coroner’s bullet-wound analysis in 1996. Now, the Georgia Innocence Project is investigating it as a wrongful conviction.

Innocence Project attorneys argue that Darrell Lee Clark was playing Russian Roulette with his friend, 15-year-old Brian Bowling, when Bowling shot himself.

“This is actually not a murder case at all,” Project senior attorney Christina Cribbs, said. “He accidentally shot himself in the head, and he died, unfortunately.”

In Clark’s trial, the deputy county coroner, Craig Burns, who had no medical expertise, said there were no visible powder marks on the victim, which meant the fatal shot was not a close-contact wound. Such a finding would negate the idea that it was a self-inflicted injury.

“The coroner's decision and observation in this case was one of the critical things that even got the case moving to a murder,” Cribbs said.

The trial court allowed the coroner to give his lay opinion, but he was not certified as an expert witness because, among other things, he admitted that examination by microscope would have been necessary to provide a scientific opinion of whether gunpowder was present, according to an appeal made to the Supreme Court of Georgia in 1999. (The testimony was allowed by the appellate court because it matched that of a surgeon who treated Bowling after the incident).

The coroner’s determination served to validate the version of events that prosecutors presented to the jury — Brian’s best friend conspired with Clark to murder Brian.

“It became a situation where the family was not willing to believe that this could’ve been a suicide or an accidental shooting, and they encouraged the police very strongly to go back to the drawing board,” Cribbs said. “It kind of got spun to a murder case.”

The distance between the shot fired and the gunshot is usually determined during an autopsy by a medical examiner to help distinguish between suicide, a self-defense killing, manslaughter or homicide.

No autopsy was performed in this case. Under current Georgia Law, an autopsy is required in deaths occurring as a result of violence or by suicide or causality, among other reasons.

When a medical examiner of a neighboring county reviewed Burns' report, including photos of the wound, he disagreed with the conclusions.

For the medical examiner, “it was obvious and not even a close question that this was a close contact or contact gunshot wound, which fits in perfectly with the fact that he accidentally shot himself while he was playing with the gun,” Cribbs said.

The medical examiner testified as a witness for the defense at the trial, but the jury still found Clark guilty.

The Georgia Innocence Project is planning on challenging the conviction in court in the upcoming months.

To become a coroner in Georgia a person must have a high school diploma or equivalent and complete basic training at the police academy. Medical examiners are required to have a medical degree, be licensed to practice medicine, be eligible for certification by the American Board of Pathology; and have at least one year of medico-legal training or one year of active experience in a scientific field in which legal or judicial procedures are involved at the county, state, or federal level.

Cribbs and Meagan Hurley, another attorney with the Project, agree that abolishing the coroner's system and replacing it with medical examiners can reduce errors in determining the cause of death.

“I think there should be a medical examiner making these decisions, as opposed to coroners,” said Hurley.

The ‘Not So Good Ones’

John Goble was re-elected as Scott County coroner in 2018 — several months after he was indicted.

The office of then-Scott County, Kentucky coroner John Goble, who served in office for about 20 years despite multiple allegations of misconduct. Emma Keady/University of Missouri and MCIR

The legal process was mired in a series of delays, one of the last of which was Goble’s defense team asking the court to run mental competency tests to determine if Goble was competent to stand trial. They found that he was.

However, Goble’s confidence in his mental capacity for the courtroom seemingly did not apply to his job performance. According to court records, Goble stated he would retire from his position as coroner of Scott County on March 11, 2022, but according to staff, he was still at work as the legal proceedings wore on.

Finally, in May, Goble pleaded guilty in federal court to conspiracy to commit theft of weapons and ammunition belonging to Kentucky State Police. Goble, now 68, resigned from office and announced he would not seek re-election. He declined comment for this story through his attorney.

On Sept. 23, he was sentenced to a year of home detention with two years probation and a $10,000 fine. U.S. District Judge Gregory Van Tatehove said he considered Goble’s health and the fact he took responsibility for his actions.

Goble also pleaded guilty in August to a state-lever perjury charge related to the weapons and ammunition case. On Oct. 3, he was sentenced in Scott County Court to one year probated to five years.

Jimmy Pollard, liaison for the Kentucky Coroners Association and retired Henry County coroner, said his organization doesn’t have much authority over coroners.

“We’re not a governing body. I can’t call this coroner and say, ‘Hey, this is the way you got to do it,’” Pollard said. “I can suggest to them, and ask them to do it. But that doesn't mean they have to. I can't tell them how to run their own department.”

Kenya Brumfield, assistant professor in criminology and criminal justice at St. Louis University, says there’s only one real solution to improving the quality of coroners in America.

“The coroner needs to be a medical professional,” she said. “They need to be a doctor, they need to have at least held a medical license.”

But with entrenched systems in place, healthcare professionals in short supply in rural areas and the electorate in charge in many states, Pollard takes a more pragmatic view.

“You know, just like corners and sheriffs and everybody, you'd have good ones and you got not so good,” Pollard said. “And you just hope these not so good ones don't abuse it, and you just have to keep stressing that.”

Reporters Claudia Rivera Cotto, Ashley Arneson and Sam Olsen contributed to this report. Additional research was conducted by Yasmeen Saadi and Dylan Schwartz.

This story was produced by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting and funded in part by the Fund for Investigative Journalism. It was also produced in partnership with the Community Foundation for Mississippi’s local news collaborative, which is independently funded in part by Microsoft Corp. The collaborative includes MCIR, the Clarion Ledger, the Jackson Advocate, Jackson State University, Mississippi Public Broadcasting and Mississippi Today.