Junk science tilts justice against those charged with crimes

Misuse of what is regarded as "junk science" -- like bite mark evidence -- has been used to send innocent people to prison and contributed to nearly half of the exoneration cases involving DNA in the U.S., according to a recent report from the Innocence Project. Shutterstock

By Susanna Granieri

Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting

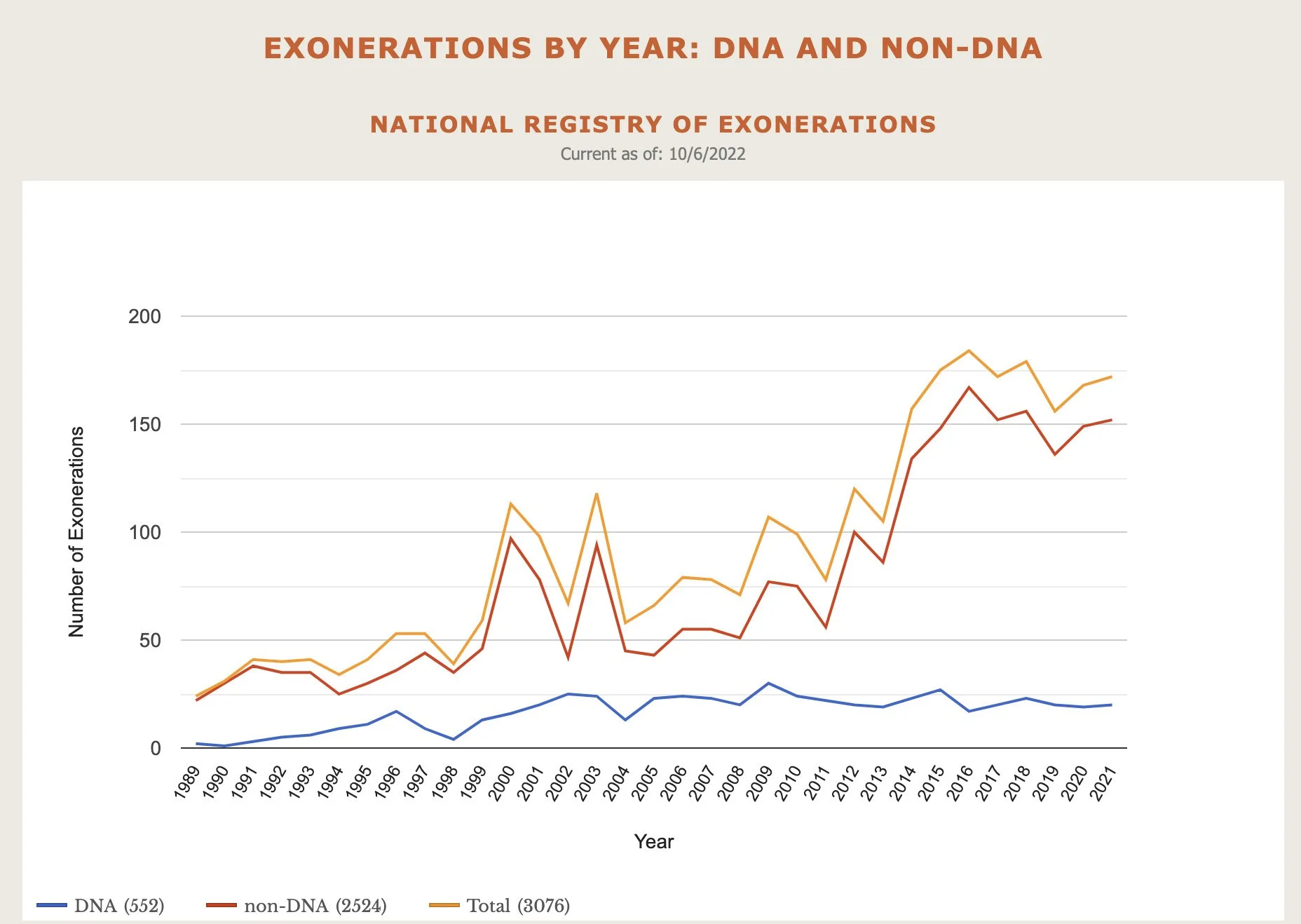

More than 3,200 Americans have been wrongfully convicted in recent decades, more than half of them because forensic science has been misapplied, or worse, the evidence is false.

The Department of Justice defines forensic science as the analysis of “evidence from crime scenes and elsewhere to develop objective findings that can assist in the investigation and prosecution of perpetrators of crime or absolve an innocent person from suspicion.”

Chris Fabricant, director of strategic litigation for the Innocence Project, said some of what passes for forensic science is nothing more than “subjective speculation masquerading as science.”

That “junk science” typically tilts in favor of the prosecution, he said. “The trouble with so many forensic tests that are done is that they're done to advance the prosecutor's case. The adversarial system is a terrible place to separate sense from nonsense.”

Fingerprints and DNA are universally accepted, but some other items, once seen by courts as proper evidence, are now regarded as junk science, such as bite-mark identification and hair analysis.

Many Americans went to prison because of shaken-baby syndrome, once believed to be absolute proof of fatal child abuse. Courts have begun to throw those convictions out because of a lack of science to back up those claims.

Through his book, Junk Science and the American Criminal Justice System, Fabricant said he is trying to create a new genre — not true crime, but “untrue crime” — showcasing misused forensic science and its impact on innocent people.

That misuse has contributed to nearly half of the exoneration cases involving DNA in the U.S., according to a recent report from the Innocence Project. They examined more than 350 DNA exonerations across the U.S., and found that 45% of these cases involved the misapplication of forensic science through unreliable methods, like bite marks.

According to data from the National Registry of Exonerations, “false or misleading forensic evidence” has contributed to “24% of all wrongful convictions nationally.” Fabricant said people of color are too often the victims of junk science.

The nation has already seen 3,261 exonerations since 1989, and Black Americans now make up more than half of them, despite the fact they comprise only 13% of the U.S. population.

“What most people don’t understand is that what we think of as scientific evidence is often not scientific at all,” said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, a national nonprofit founded in 1990 that focuses on sharing data, analysis and information on capital punishment.

“There are whole areas of forensic science that are completely junk,” he said, “or that are more art than science and are so subjective that a prosecutor will be able to find some expert somewhere to say what the prosecutor wants.”

The more heinous a homicide, Durham said, the more likely authorities are to resort to unreliable evidence in trying to solve it.

In particularly violent or emotional cases, the risk of police and prosecutors using unreliable evidence is heightened. This faulty evidence could include jailhouse informants, who may be promised freedom in exchange for testimony against suspects.

Clear examples of this are in cases where children have died and parents are charged with the murder, but it’s later found the children died from natural or accidental causes.

“Forensic science has tremendous potential for good and has been a tremendous force for injustice,” Dunham said.

Fabricant said the Innocence Project has pushed for improvements in the use of forensic evidence. The FDA regulates the safety of mouthwash or toothpaste, but there is no such oversight in forensics, he said.

Alicia Carriquiry, director of the Center for Statistics and Applications in Forensic Evidence, said subjective scientific evidence isn’t always bad, but error rates are tough to estimate.

An error rate is the likelihood an examiner is providing the correct conclusion and how different variables, like human error and biases, may impact the results. Many times, Carriquiry says, error rates have not been estimated.

“You don’t really know whether the conclusion that the examiner or the expert witness is presenting is the correct conclusion or not, and that’s of course problematic.”

Dr. Itiel Dror, senior cognitive neuroscience researcher at University College London, says these conclusions can be swayed because of conversations examiners may have with police. He calls it “suspect target bias.”

“If you come to the autopsy with a preconceived notion of what happened, that impacts what you look for, how you perceive what you see, and how you interpret it,” he said. This type of “working backward,” he says, has experts working from the suspected target to the evidence, rather than letting the forensic evidence lead the process.

“Police and forensic scientists should be independent of one another,” he said. “This is one big problem: They work as a team.”

Junk science has ‘led to countless wrongful convictions’

As of April 2022, the Mississippi State Medical Examiner’s Office was backlogged by 1,300 reports dating to 2011, according to AP. The National Association of Medical Examiners is responsible for accrediting U.S. death investigation offices; Mississippi’s medical examiner’s office has never been accredited.

Dr. James Gill, the chief medical examiner of Connecticut, said accreditation gives forensic labs and offices many advantages, such as giving confidence to stakeholders that cases are being properly and professionally handled. For example, Gill said no one would want to go to a blood bank that’s unaccredited. The same value applies to forensics organizations.

“Work can really save lives, and if we make a mistake, people can go to prison for the rest of their lives,” Gill said. “So we want to make sure that we're doing things properly and we're meeting professional standards, and so by accreditation that helps demonstrate that we are meeting those.”

Mississippi Public Safety Commissioner Sean Tindell, who stepped into his role in 2020, said the office is in the process of hiring more pathologists to complete the autopsies in a timely manner, and “anticipates having the backlog eliminated in the next year.”

The national association’s guidelines state that each pathologist should only handle approximately 325 autopsies per year (250 is the ideal maximum), and Tindell said while the medical examiner’s office is over that number, he is hopeful. Chief Medical Examiner and forensic pathologist Dr. Staci Turner says once the backlog is handled, they hope to be accredited.

Tindell believes the “[medical examiner’s] office is a very important part of the justice system, and ultimately what we want is justice to be served. If at any time there’s new information that needs to be considered, we’re certainly willing to take a look at that.”

But, while Mississippi has dealt with an uptick in exonerations, Turner says she has not been asked to review past autopsy reports or testimonies in any cases since she stepped into her position this past year.

Hattiesburg dentist and forensic odontologist Michael West is well-known in Mississippi for his application of junk science in dozens of testimonies against defendants. West, with his confident and homespun manner, repeatedly assured juries his bite-mark analysis was undeniable.

But, in 2008, his method and expert opinion was questioned after Levon Brooks and Kennedy Brewer, convicted of murder in Mississippi in separate cases, were exonerated based on DNA results — West provided crucial testimony in both of their convictions.

In September 1990, 3-year-old Courtney Smith was abducted from her Brooksville, Mississippi home, and her body was found two days later — she had been sexually assaulted.

Brooks was an immediate suspect because of his former relationship with Smith’s mother. Dr. Steven Hayne performed the autopsy on Courteny’s body, and after discovering what he thought might be bite marks, referred the case to West.

West took dental impressions of the bite marks and said they were from a human. Smith’s 5-year-old sister testified she saw the perpetrator and directed the investigation towards Brooks. West took a sample of Brooks’ teeth, and testified that two of Brooks’ teeth matched the marks on the toddler. This resulted in a capital murder conviction, and Brooks was later sentenced to life in prison.

A few months later, another 3-year-old girl, Christine Jackson, was abducted, raped and murdered in Brooksville, but this time, investigators pointed their finger at Brewer, the boyfriend of the victim’s mother.

Once again, Hayne conducted the autopsy, found what he thought might be bite marks and referred the case to West, who came up with another perfect match, and Brewer was sentenced to death.

DNA tests that were later conducted showed the real killer was Justin Albert Johnson, who had been a suspect in both investigations. When authorities interrogated him, he admitted to both murders, but denied biting either victim.

Even after the exonerations of Brewer and Brooks, West insisted to MCIR founder Jerry Mitchell that both men had bitten the girls before they were killed.

Both young girls were found near a water source — Courtney near a pond and Christine near a creek — but West ruled out the possibility of animal bites in his testimonies. It was later found that crawfish were to blame for the bite marks on the victims’ bodies.

“Everything you need to know about the history and the use of junk science can be learned through the history of bite-mark evidence,” Fabricant said. “You can see how one case gets into court one time and then it's like a virus that spreads through our system. It’s led to countless wrongful convictions.”

The exonerations of Brewer and Brooks caused investigations into Hayne and West’s practices. Hayne said he had conducted between 1,200 to 1,800 autopsies a year throughout Mississippi — six times the professional standard — and earned more than $1 million dollars per year.

The state of Mississippi soon cut ties with Hayne, who is now deceased, and West later said he no longer believed in bite-mark analysis.

Brooks spent 16 years in prison before his exoneration, and Brewer spent 13. Each was given $500,000 in relief due to their wrongful convictions, and were a crucial part of Mississippi’s pivot towards the use of reliable forensic evidence.

Levon Brooks and Kennedy Brewer, convicted of murder in Mississippi in separate cases, were exonerated based on DNA results that showed the real killer was Justin Albert Johnson. Brooks spent 16 years in prison before his exoneration, and Brewer spent 13. Mississippi Book Festival

Can ‘cold-blooded’ advanced technology eliminate bias?

Advanced technology will lead to different types of forensic science review, says Robert Thompson, senior forensic science research manager at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. He says the objective findings, though, will only be complementary to expert testimony, and will not replace it.

The technology will add to the training, research and experience of examiners, he said, and could support or contradict their subjective opinion.

“This technology is independent of where it is going to be used,” Thompson said. “Adding the value of an objective measurement helps to maybe eliminate or control biases or anything like that, because it's cold-blooded, and it tells the examiner whether [they’re] making the right opinion or not.”

But Fabricant has his doubts. Just because technology advances doesn’t mean it pushes toward justice, he said.

“What we need is a scientific agency, something like his national institute, to do validation research and demonstrate that these techniques are reliable before they can be used in any criminal case,” Fabricant said.

This would allow independent verification of wild claims sometimes accepted as evidence in criminal trials, he said.

Thompson says people are interested in the objective measurements of technology, even though he believes subjective comparisons are accurate.

“Juries are getting wiser,” he said, “and they want to hear a little bit more about what’s the basis for the examiner’s opinion.”

Dror agrees with Thompson, as technology will provide that objective lens with juries. But, biases that people who create the technology have, or how people interpret the results, may impact the accuracy of their conclusions.

“The technology may be testifying [to the accuracy of the conclusion], but the human is talking,” he said.

DNA is nearly 100% accurate when a large sample is analyzed properly, says Becky Steffen, forensic DNA scientist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. But such large samples are rarely the case.

A more sophisticated type of DNA testing, known as probabilistic genotyping now exists, enabling scientists to test mixtures that include DNA by different people.

Fabricant marvels at the advanced technology, but worries it could lead to wrongful convictions.

Expert testimony is normally paid for by the state at the request of the prosecution, and many of those experts are from the state Crime Lab. They are supposed to be “neutral, but they’re not because they work for the Department of Public Safety — the largest police organization in the state,” said Mississippi State Public Defender André de Gruy.

“The problem in most cases is the defense doesn't get anyone, and they're dependent upon the state expert to not only tell the truth, but to tell the whole truth,” de Gruy said. “If somebody's paying you and they're not asking you for the whole truth, you might not give the whole truth.”

Since the defense then cannot have the expert testimony reviewed by another scientist, it’s difficult to challenge their version of truth, de Gruy said.

Some defense lawyers don’t push for funding for experts because they’ve never received it in the past, de Gruy said. More than half the circuit judges in Mississippi are previous prosecutors.

“Judges would bristle at the idea that they’re on the same page as the prosecutor because by law they’re neutral,” he said, “but they don’t have the experience to understand why you need someone, even if it’s just a consulting expert, so that you can understand what the state’s experts are saying.”

Dror says that, while pathologists and examiners may be aware their conclusions could be subjective and subject to different biases, they don’t outright share that with the jury.

“The problem with being honest with the jurors is that they do not want to hear ambiguity,” Dror said. “They want to know definitely if the person is guilty or innocent. They want a clear conclusion and they want the scientists to take the burden off of them and give them a conclusive answer.”

Dror believes the legal system pushes scientists to not explain the complex nature of their conclusions, as they only care about an innocent or guilty verdict, not what happens in between.

With popular shows like CSI showcasing forensic science, juries may expect forensic evidence, and, when they see such evidence, combined with expert testimony of someone in a “white lab coat,” it can sway them, Dror says.

The CSI effect encourages this type of end-all, be-all mentality with juries, as an increased interest in true crime has led to an uptick in “couch detectives,” Steffen says. This distortion impacts a jury's ability to understand the intricacies of DNA and forensic evidence analysis, as crime TV makes the process look simple, fast and undeniable.

“There is so much technology out there that people are just demanding DNA. There’s no real evidence that that’s actually happening in court, but I think it helps strengthen a case,” she said. “Juries really like to see that if there's a match, then there's no arguing with it.”

The CSI effect is not the only aspect of forensic science that impacts juries, but a highly emotional case, where a baby is dead, causes desperation from police and prosecution to find the killer, said Dunham.

“They are much more likely to resort to questionable evidence, and juries are persuaded by it,” he said.

A 2014 study from the University of Denver investigated whether, as the seriousness of a crime increased, so would the use of erroneous evidence. Are crimes that have the highest stakes, like a death sentence, the ones that use the most unreliable evidence?

“If that’s true,” said Scott Phillips, professor of criminology at the University of Denver and researcher on the study, “then it suggests a problem with the death penalty that the worst crimes often attract the worst evidence.”

While it was found that the more serious crimes had a higher probability of different types of problematic evidence, such as false confessions, Phillips says it's hard to know if that translates correctly as the data sample only included known wrongful convictions.

“It's clear that as the crime gets worse, the chance of a false confession goes up. But we can't say for certain what's happening there,” Phillips said. “But what we think is happening is, [for example], the police aren't going to push as hard as they can for a stolen bicycle. But when there's a rape and murder and torture, the interrogation room probably looks really different.”

Of the 190 exonerations from death row, DNA played a central role in 29 of those cases, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Florida leads with 30 total exonerations, Illinois follows with 21, Texas with 16 and North Carolina with 11. But, over the past seven years, the number of exonerations from Mississippi’s death row has more than doubled, from three to seven.

This means that about 85% of exonerations have nothing to do with DNA, but Dunham begs the question: “So why is DNA important?”

When DNA is conclusive, Dunham said, it can exclude a defendant — there is no “he said, she said” situation, or a question of witness reliability.

“The DNA evidence isn't always conclusive. There are times in which it suggests innocence, but doesn't necessarily prove it,” Dunham said. “But when it suggests innocence, and you have other red flags of innocence, that's it. That is objective confirmation of what otherwise might be a subjective judgment.”

There were a total of 161 exonerations in the U.S. in 2021; 102 involved official misconduct, 47 involved mistaken witness identification, 107 involved false accusations or perjury, and 33 involved false or misleading forensic evidence.

Dror described his own ABCs: “assume nothing, believe nothing, check everything.”

“If forensic pathologists just followed the ABCs,” he said, “there would be less wrongful convictions, and less guilty people who may go free.”

Email Jerry.Mitchell@MississippiCIR.org. You can follow him on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

This story was produced by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting and funded in part by the Fund for Investigative Journalism. It was also produced in partnership with the Community Foundation for Mississippi’s local news collaborative, which is independently funded in part by Microsoft Corp. The collaborative includes MCIR, the Clarion Ledger, the Jackson Advocate, Jackson State University, Mississippi Public Broadcasting and Mississippi Today.