After Roe, Pregnancy in Mississippi Could Be Criminalized More Often

Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Mississippi’s sole remaining abortion clinic, will go out of business on July 7, pending its lawyers’ appeal to the Mississippi Supreme Court. But the scene out front on the last day that the clinic is open remains very lively: A young woman who supports the Pink House, as JWHO is called, holds up a neon pink poster proclaiming abortion is protected under the right to privacy.

Across the street, a regular antiabortion demonstrator, a middle-aged man, gets a loud, long honk of support from a passing car.

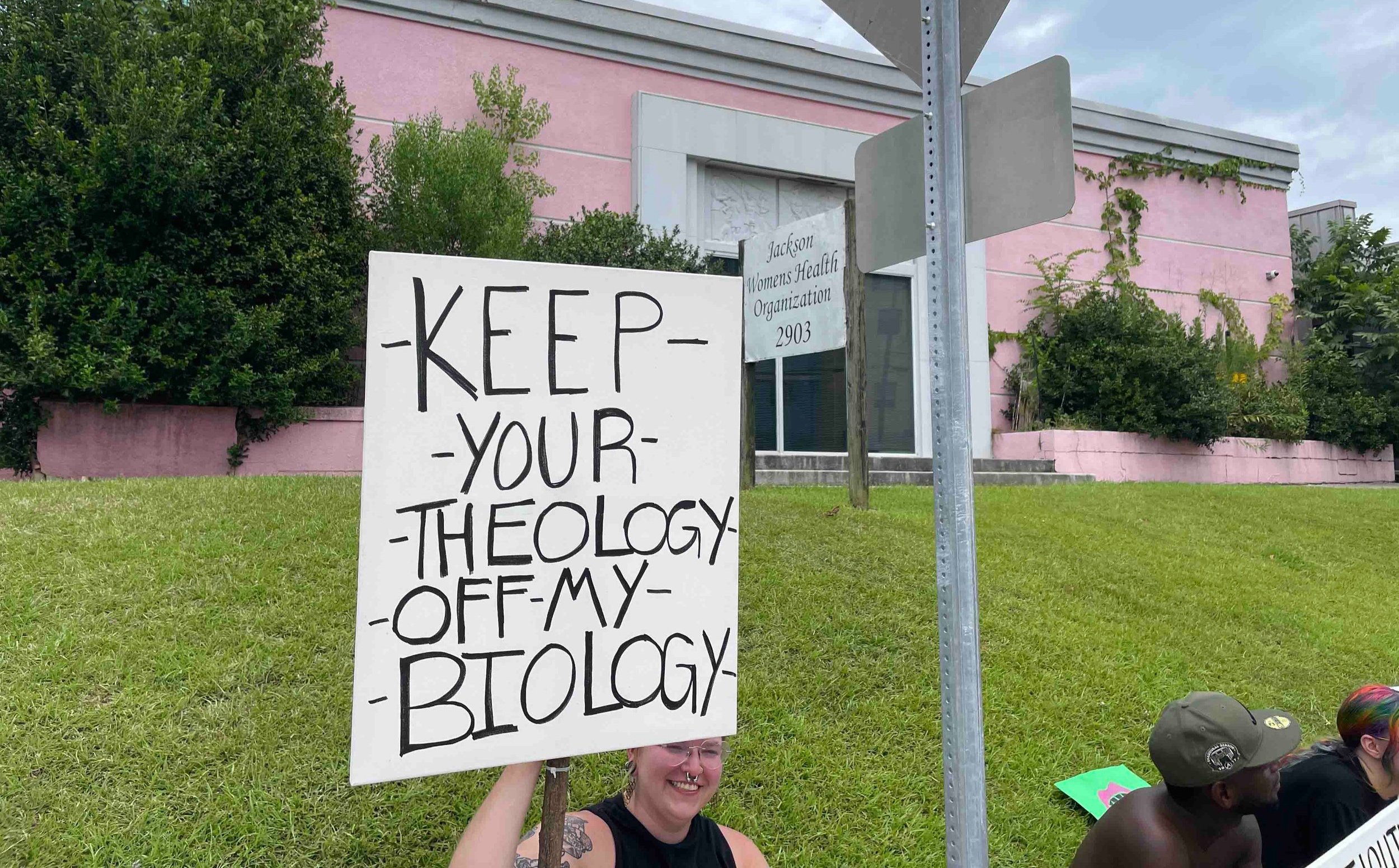

Pro-choice supporters hold signs July 2, 2022, in front of Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which Is still offering abortions. Ann Marie Cunningham/MCIR

“Incoming!” shout the Pink House Defenders, the clinic escorts, as a client’s car turns into their parking lot.

On July 5, in Hinds County Chancery Court, Judge Debbra K. Halford heard arguments from the Mississippi Center for Justice, the Center for Reproductive Rights, whose lawyers represented JWHO before the Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, and New York law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. This legal team filed for a restraining order for JWHO on the basis of a 1998 decision by the Mississippi Supreme Court that ruled that abortion was legal according to the Mississippi state constitution.

Halford denied the clinic’s request for a temporary restraining order, so JWHO’s legal team will appeal immediately to the Mississippi Supreme Court. Nevertheless, the Pink House will close, and the organization will open the Pink House West in Las Cruces, New Mexico’s second largest city whose residents are more than 60 percent Latino. Diane Derzis, the clinic’s executive editor, said the new clinic is likely to be painted in colorful stripes, like a box of crayons.

In states like Mississippi without abortion clinics, women are expected to turn to medical abortions. Internet searches for information about abortifacients have soared since January, when a preliminary opinion overturning Roe v. Wade was leaked from the Supreme Court. In Mississippi, that means that women may become vulnerable to conservative prosecutors who can charge them with homicide. Prosecutors here have already trained spotlights on mothers whose infants are stillborn or who die shortly after birth.

At the Pink House abortion clinic in Jackson, Miss., a supportor holds a sign that draws a link between the overturning of Roe v. Wade to a violation of the First Amendment’s separation of church and state. Ann Marie Cunningham/MCIR

For example, in 2006, in Lowndes County on the eastern state line of central Mississippi, 16-year old Rennie Gibbs gave birth to a baby girl who was stillborn. She arrived a month premature with her umbilical cord wrapped around her neck. The late Steven Hayne, who was Mississippi’s controversial state pathologist until 2008, found a cocaine byproduct in the baby’s blood and decided it had been the cause of her death. Prosecutors linked Gibbs’ daughter’s death to her use of cocaine.

Other experts, who examined the medical record later, ruled the most likely cause of the baby’s death was her umbilical cord. Gibbs is Black, and African-American mothers are more likely to suffer stillbirths. Black women have 2.2 fold increased risk of stillbirth compared to White women, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Early in 2007, a Lowndes County grand jury indicted Gibbs for murder of her daughter. Gibbs had to spend the next seven years fighting the charges, which were finally dropped in 2014. She was represented by Robert McDuff of the Mississippi Center for Justice, a member of JWHO’s legal team that filed for a restraining order.

Gibbs escaped becoming the first Mississippi mother to face life imprisonment for killing her child before birth. In 2017, three years after Gibbs was exonerated, another Black mother, Latice Fisher, a police dispatcher in Starkville, gave birth to a premature stillborn baby boy at home in Oktibbeha County, just east of Lowndes County. Fisher, 32, already had three children. Because she had researched medical abortion online, an Oktibbeha County grand jury charged her with second-degree murder.

Earlier this year, prosecutor Scott Colom dropped charges against Fisher. But one of her lawyers, Emma Roth at the nonprofit National Advocates for Pregnant Women in New York, is sure that, as medical abortions become more and more popular, more women like Fisher are likely to be indicted.

Eventually, in one of these cases in Mississippi, a murder charge may stick.

Ann Marie Cunningham is MCIR’s Reporter in Residence. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.