Going Hungry and Getting Fat During the Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has left jagged tears in America’s social fabric, including losses of jobs and health insurance, and the disparities between infection rate, access to health care, and deaths among whites as opposed to those of people of color and poorer communities. But perhaps no rip is more devastating than what experts call “food insecurity” —not having enough to eat, going to bed hungry, starving—which affects millions of Americans.

The New York Times, which prides itself on being “the newspaper of record,” rarely takes note of Mississippi unless there is a new top elected official or a new flag. Then in early September 2020, its Sunday Magazine showcased some of the nearly one in eight U.S. households that don’t have enough to eat, and must rely on food banks and meals from churches and nonprofits.

The Times Magazine’s full-page photographs show these hungry Americans in 13 cities, from Oneida, New York, to San Diego, California. Jackson, Mississippi, is the only city represented by three pages of photos and reporting. One Black woman is shown wheeling home groceries from local nonprofit Stewpot Community Services. During the pandemic, Stewpot has been delivering food to older residents, but this woman told the Times Magazine that walking is good for her diabetes. A second photo shows seven Black children saying grace over their meals from Stewpot and a nearby church. A third photo shows a shirtless Black 4-year old paying for a corn dog over the counter of a convenience store, with a rack bulging with bags of chips and sweet rolls behind him.

Hungry Mississippians first entered the spotlight 53 years ago, in the spring of 1967.

That April, at the behest of young NAACP lawyer Marion Wright (the future Marion Wright Edelman, founder of the Children’s Defense Fund), Robert F. Kennedy, then the Democratic senator from New York, along with another member of the Senate subcommittee on Employment, Manpower, and Poverty, visited several very poor homes in the Delta, the poorest region in Mississippi. There was no Medicaid yet (Mississippi did not adopt the program until 1970), no free school breakfasts and lunches, no federal food aid for mothers, few jobs —and food stamps cost money, $2 per person per family. If a family received free federal commodities, they were ineligible for food stamps as well.

Kennedy was overwhelmed by what he saw: barefoot children showing the classic signs of starvation — spindly arms and legs, bloated bellies, listlessness, open sores on their faces and all over their bodies. For the remaining 14 months of his life, Kennedy spoke constantly about the suffering he had seen in Mississippi, and how he believed that children, even babies, starving along with adults was “unacceptable…simply unacceptable.”

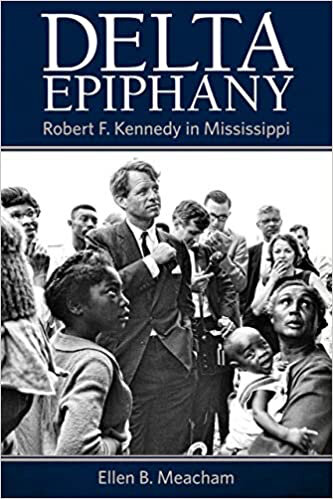

The cover of Delta Epiphany: Robert F. Kennedy in Mississippi by Ellen B. Meacham

In Delta Epiphany: Robert F. Kennedy in Mississippi, journalist Ellen B. Meacham reports that after Kennedy’s trip, he and the other senator who had visited the Delta fought for a federal nutrition survey, the first to study hunger in the U.S. It showed that in every single region of the country, pockets of citizens were as malnourished as people in underdeveloped nations.

Today, hunger is still a problem in Jackson and in the communities that Kennedy visited, though it looks very different. Although no one overweight appears in the Times Magazine photographs, Mississippi leads the United States in obesity. Much of it is caused by reliance on the cheapest food available: starches, fast food, and donations.

Before I left New York City for Mississippi, I sampled free meals given out by the city and two churches. All featured very filling bread, corn, chips, cereal, pasta, potatoes and cookies— along with one apple or orange and a handful of raw carrots. I had no problem putting on the proverbial “Quarantine 15” and more -- even though I ate only two meals a day. I’m sure these meals I got are similar to what families receive here: One of The New York Times Magazine photos shows Jackson children eating fried potatoes, fried catfish and corn, with cookies and a single mango for dessert.

I heartily thank Stewpot, the City of New York, and churches all over the country that are working hard to fight hunger during the pandemic. Here, you can see more Americans who are struggling to put food on their kitchen tables.

Ann Marie Cunningham is a Columbia University Lipman Fellow for 2020 who will be working with the Mississippi Center for investigative Reporting. She is a veteran journalist/producer and author of a best-seller. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Technology Review, The Nation and The New Republic. Contact her at amclissf@gmail.com.