MCIR LIVE Explores 1963 Bombing in Birmingham: ‘It Is Never Too Late for a Man To Be Held Accountable For His Crimes.’

Four people who contributed to a major chapter in civil rights history joined MCIR founder Jerry Mitchell last week to talk about justice achieved after almost 40 years. Two lawyers who had refused to allow Ku Klux Klan members to get away with a truly terrible crime, a ground-breaking jury consultant who had volunteered to help, and the younger sister of one of the four victims joined in an extraordinary conversation with Mitchell, whose reporting helped the prosecution convict the killers. None of them has ever forgotten a Sunday in September in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963 — even though one of them had yet to be born.

On Sept. 15, 1963, a bomb planted by the Ku Klux Klan detonated in Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church. The church was the Klan’s target because it had been the focal point of the Children’s Crusade. All summer, Black girls and boys in Birmingham had been marching for civil rights, defying Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor’s fire hoses and attack dogs.

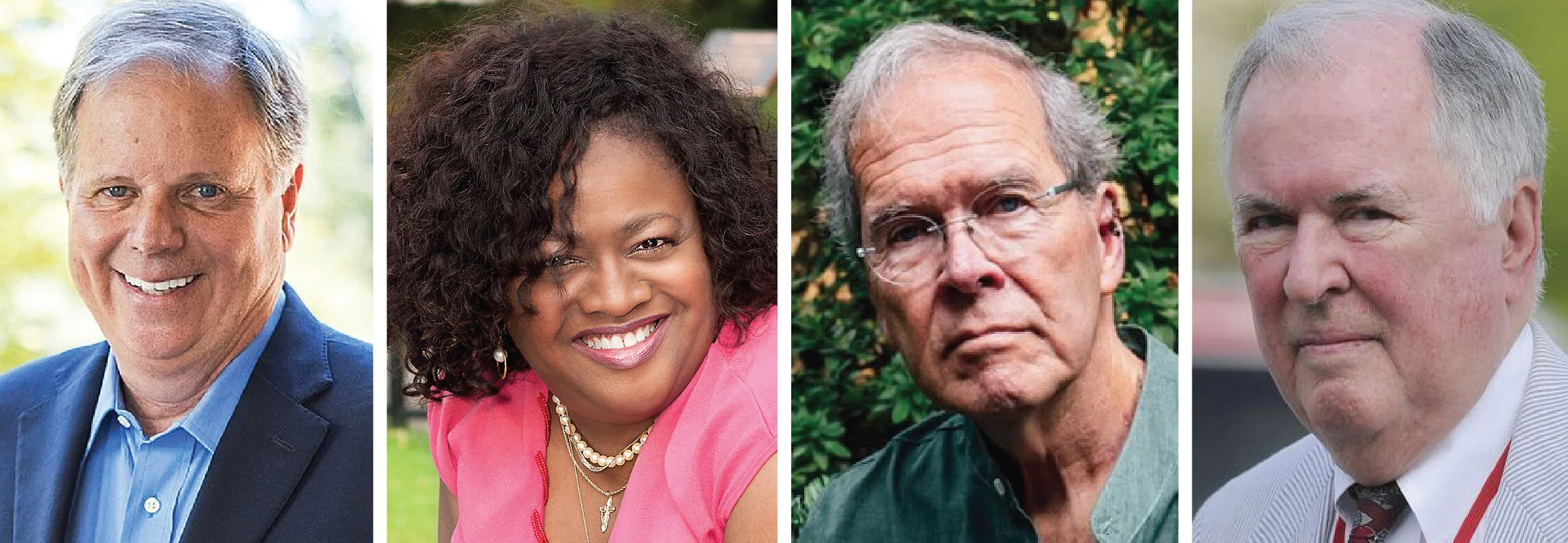

The MCIR LIVE event, "Confronting Domestic Terrorism," featured former U.S. Sen. Doug Jones, who won convictions against two Klansmen involved in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing that killed four girls; Lisa McNair, whose older sister Denise was killed in the blast; jury consultant Andy Sheldon, who worked on the prosecution team; and former Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley, who won the first conviction in the case.

The Klan’s bomb went off just before the Sunday church service. It tore out the ladies’ lounge in the church basement, where five young girls were primping in their Sunday best before the service. Four of them were killed. The last thing the lone survivor remembers is seeing her older sister, 14-year old Addie Mae Collins, tie a dress sash for the youngest, 11-year old Denise McNair. Denise’s father was a photographer, and his favorite picture of her showed her hugging her white, blonde Chatty Cathy doll.

McNair’s sister Lisa was born “a year to the day after my sister was killed.” Today, Lisa McNair frequently speaks to high school students about 1963, and has a book coming out next year, Dear Denise: Letters to the Sister I Never Knew. The memory of Denise’s awful loss permeated her parents’ lives, Lisa’s own childhood and Black Birmingham. People rarely talked about that Sunday — at least not until 1997, when Spike Lee’s documentary, Four Little Girls, prompted conversations.

In 1963, Bill Baxley, whose family roots in Alabama go back to the 1700s and whose four great-grandfathers fought for the Confederacy, was in his last year of law school. That Sunday, after Baxley heard about the bombing, “I couldn’t eat. I felt ill all day.” The FBI came to Birmingham to investigate the bombing. Baxley was prepared to take time off from law school to help the FBI any way he could: “I’d have fetched coffee, hot dogs, law books.” The FBI fingered four suspects, but never made a case; no one went to trial. Klan members boasted to friends and family that they had gotten away with murder.

Then, in 1970, Baxley was elected the youngest attorney general in Alabama history. He was given a government-issued phone card, which he carried everywhere. “I wrote each name of the girls on the four corners of my card.” For five years, he got no cooperation from the FBI until journalist friend Jack Nelson, a fellow Alabamian, intervened. Baxley persevered with his conviction of “Dynamite Bob” Chambliss, who had built and set so many bombs in Black neighborhoods that Birmingham became known as “Bombingham.” When Chambliss’ wife was told he was going to prison for life, she rejoiced: Chambliss and other Klansmen involved in the bombing were domestic abusers.

Despite Chambliss’ conviction, Baxley was frustrated that three other Klansmen were still free. “I didn’t know there was a kid sitting in the gallery of the courtroom” who would change that, Baxley said during the April 8 MCIR LIVE event. Birmingham law student Doug Jones wanted to be a trial lawyer. Associate Justice of the Supreme Court William O. Douglas had told Jones, “If you want to be a good lawyer, go watch good lawyers.” So Jones cut his law school classes to watch Baxley “give a master class” in his courtroom: “Bill’s closing argument instilled in me a sense of history … a sense of purpose.”

In 1997, as Lee’s Four Little Girls focused national attention on Birmingham, then-President Bill Clinton appointed Jones U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Alabama. Finally in a position to do something for the victims’ families and community, Jones was determined that “justice delayed doesn’t have to be justice denied, even though there was injustice in the delay.”

Ground-breaking jury consultant Andy Sheldon volunteered to help Jones, joining his self-described team of “inside agitators.” Sheldon had helped prosecutors choose the Mississippi jury that in 1994 convicted the killer of Medgar Evers, and went on to help select the jurors that in 2005 convicted the Klan leader who orchestrated the slayings of three young civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Every day, Sheldon carried into the courtroom a box containing “a young girl’s black patent leather dress shoes” and Denise McNair’s father’s photo of her with her doll. “The Klan was so good at instilling fear,” he said, “and they were remorseless.” Jones added that they had “ice water in their veins.”

One Klansman involved in the bombing had died. But in the same courtroom where Baxley had convicted Chambliss, Jones was able to put the two others behind bars for the rest of their days. Lisa and her parents were in the front row daily, as they had been during Baxley’s prosecution. When Jones’ second verdict came down, Lisa said, “everyone cried — the prosecution, too. It was justice for all of us.”

Today Sheldon paints scenes from the civil rights cases he’s worked on, and has an upcoming show at Emory University School of Law. Sheldon pointed out that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently stated that “racism is a serious public health problem.” The Klan is still around in some modern groups, he said. MCIR LIVE participants agreed that recent rhetoric from elected officials encouraged violence in the same way as then Alabama Gov. George Wallace’s 1963 statement that to stop integration, Alabama needed “a few first-class funerals.”

“Anti-racism works for me,” Sheldon said. “It’s over; I’ve had enough.”

In his Klan cases, Jones said, “reporters and prosecutors needed each other. Reporters were there to support the truth.” Jerry Mitchell closed the conversation by noting that “these cases are evidence of what journalism can do.”

May MCIR LIVE’s historic conversation inspire a new generation of civil rights lawyers and reporters.

For more about 1963’s “Birmingham Sunday,” see Doug Jones’ book, Bending Toward Justice: The Birmingham Church Bombing That Changed the Course of Civil Rights. During the second trial, Jones prepared his closing argument by rereading Jackson, Mississippi, district attorney Bobby DeLaughter’s Never Too Late: A Prosecutor’s Story of Justice in the Medgar Evers Case. Birmingham native and reporter Diane McWhorter witnessed Jones’ trials and wrote about them in Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama, The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution. So did Jerry Mitchell in Race Against Time: A Reporter Reopens the Unsolved Murder Cases of the Civil Rights Era.

Ann Marie Cunningham is a Columbia University Lipman Fellow for 2020 who will be working with the Mississippi Center for investigative Reporting. She is a veteran journalist/producer and author of a best-seller. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Technology Review, The Nation and The New Republic. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.