World shuns locking up juveniles for life. Mississippi, US embrace it.

Shutterstock

By Shirley L. Smith

Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting

Mississippi is not only out of step with most states in its harsh sentencing of youth, it is also behind the global community, which shuns life-without-parole sentences for children – a practice still acceptable in Mississippi.

America as a whole trails behind the rest of the world in its approach to juvenile offenders.

“Life sentences without the possibility of release for children are expressly prohibited by international law and treaties,” Juan Méndez, the former United Nations special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, said in a 2015 report. In the report, Méndez singled out the U.S. for being the “only (country) in the world that still sentences children to life imprisonment without the opportunity for parole for the crime of homicide.”

Every world leader, except the U.S., has ratified Article 37 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, a 30-year human rights treaty that prohibits imprisoning children under the age of 18 to life with no possibility of release.

“Life sentences or sentences of an extreme length have a disproportionate impact on children and cause physical and psychological harm that amounts to cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment,” Méndez said. He added that “children must be subject to sentences that promote rehabilitation and re-entry into society.”

Despite worldwide condemnation of extreme sentencing for children, The Sentencing Project found that at the end of 2016, nearly 12,000 individuals in the U.S. were serving life or “virtual life” sentences for crimes they committed as a juvenile. More than 2,000 of them were serving a life-without-parole sentence. Due to a U.S. Supreme Court ruling banning mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles who committed a homicide before the age of 18, hundreds of these so-called “juvenile lifers” have since been released or resentenced to a prison term with parole eligibility, but many will spend the remainder of their lives behind bars.

Ashley Nellis, senior research analyst for The Sentencing Project, described “virtual lifers” as individuals with prison terms of 50 years or more, which amounts to a life sentence because the sentence exceeds their life expectancy and virtually guarantees the offender will die in prison. States differ, however, in how they define what constitutes a virtual life sentence.

The Sentencing Project found that “although the United States represents just 4% of the world’s population, it holds 40% of the world’s life-sentenced population,” and the majority of youth who receive life sentences are Black. “In the Southern states of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and Virginia, over 80% of the youth life-sentenced population is African American.”

Researchers at the New York-based nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice said the number of people incarcerated in America has actually declined steadily in the past 10 years, but the U.S. “continues to lead the world in locking up its own people.” They estimate that 1.4 million people were incarcerated in state and federal prisons in the U.S. at the end of 2019, and the data show Mississippi has the second-highest incarceration rate in the nation.

“The reason we are the number two incarcerator in the world is because we have extreme sentencing,” said André de Gruy, the state’s public defender. De Gruy said many juveniles and adults in the state are serving virtual life prison terms, because of consecutive sentences for multiple offenses. The longest sentence he said he has seen for an adult is 120 years. Court records show that at least one juvenile in Mississippi was sentenced to a term of 95 years.

Alesha Judkins

Courtesy: fwd.us

The Washington D.C.-based nonprofit Justice Policy Institute also discovered that Mississippi has the second-largest percentage of Black men under the age of 25 serving long prison terms, surpassed only by Maryland.

“Black people and people of color are often disproportionately impacted by our sentencing structures,” said Alesha Judkins, Mississippi’s director for criminal justice reform for FWD.us, a bipartisan policy advocacy organization. FWD.us data show Black men make up 13 percent of Mississippi’s population, yet they represent 75 percent of people serving sentences of 20 years or more due to habitual penalties.

Judkins said Mississippi’s “incarceration crisis” stems from a multitude of socioeconomic and political factors such as its high poverty rate, disparities in its educational system, the mindset of elected prosecutors and judges, and its parole and habitual laws.

Under the state’s habitual laws, individuals with prior convictions can be sentenced to decades, even life in prison for minor offenses, Judkins said. Additionally, “two-thirds of people currently in custody do not have eligibility for parole. So, you are dealing with a situation essentially where the (Mississippi) Department of Corrections cannot safely house and manage the people in its care and custody,” she said.

The fallout from this has become apparent in this era of COVID-19, as the pandemic has further exposed how poor living conditions and inadequate health care inside a prison can be a lethal combination for inmates trapped in a cell with others, and how easily an outbreak in the prison can spill over into the community from infected staff.

On Oct. 30, MDOC reported that 809 inmates in Mississippi and 146 prison staff had tested positive for the coronavirus. At least one person has died, reported The Marshall Project, which is tracking COVID-19 infections in state and federal prisons. In a recent news release, MDOC Commissioner Burl Cain boasted that these numbers are relatively low in comparison to 30 other state prisons and the federal prison system. However, Paloma Wu, deputy director of Impact Litigation for the Mississippi Center for Justice, said these numbers are misleading because MDOC is “systemically under testing as compared to many other state and federal prison systems, and they are not testing people who are clearly symptomatic.” The nonprofit sued the MDOC in May, accusing the agency of failing to implement adequate safety precautions to protect inmates from COVID-19. MDOC would not comment on the suit but said on its website: “The MDOC is actively taking steps, based on CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) guidelines, to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 at its facilities, including testing based on symptoms and as a result of contact tracing.”

Sen Juan Barnett, D-Jackson, speaks at a Prayer for the Prisons Rally on Jan. 23, 2020, at Mississippi’s state Capitol. Barnett is a strong advocate for expanding parole eligibility for juveniles and adults and putting an end to the state’s mass incarceration crisis. Asia Allen/MCIR

The Justice Policy Institute’s analysis of the annual cost of youth confinement in the 50 states reveals that the cost to incarcerate one youth for a year in Mississippi is $155,125. “The resources needed to incarcerate a youth could be better allocated towards the (estimated) in-state tuition cost of $8,600 per year,” JPI experts said.

Sen. Juan Barnett, chairman of Mississippi’s Senate Corrections Committee, said if the state would invest more money in educating children rather than incarcerating them and help them develop a trade, they would be less inclined to turn to a life of crime.

“I think we would see less students dropping out of school, which means we have less children on the streets, which means we have less children committing crime,” he said. “It’s sad that an individual can go 12 years of school and never be offered a welding class or a mechanic class or any of those type of classes, but as soon as they are incarcerated we want to offer them all of these classes.

“As a country, we also have to realize that we can’t educate all of our children and expect them to be doctors, lawyers, bankers or whatever. Some of our kids really like using their hands,” Barnett said.

How did America fall so far behind?

America has a long history of treating children in the criminal justice system like adults. In the late 18th Century, children as young as 7 were prosecuted as adults and could be sent to prison and even sentenced to death, according to the National Center for Juvenile Justice.

The perceptions of juvenile offenders gradually changed. In 1899 the first juvenile justice court in the U.S. was established in Cook County, Illinois. It was founded on the principle that the state has a responsibility to protect children and with the understanding that children are not “miniature adults,” as such, they should not be punished like adults. The focus was on rehabilitation and turning delinquent youth into productive citizens. Other states soon followed suit and established their own juvenile courts.

Legal scholars said an increase in violent crime in the 1980s and 1990s combined with a baseless “super-predator” theory in the 1990s caused a seismic shift in the mindset of policymakers and many elected prosecutors and judges bent on proving to their constituency that they were cracking down on crime. As a result, juvenile justice policies reverted to the more punitive system.

Academic criminologist John Dilulio, who developed the “super-predator” theory, predicted “tens of thousands” of “super crime-prone young males,” depicted as Black teenage boys, would rise up and “commit senseless violent crimes without remorse or reason, according to a report by The Campaign For The Fair Sentencing of Youth.

This toxic rhetoric led to extreme penalties like mandatory life-without-parole sentences for children, said the campaign’s Legal Director Heather Renwick. More children were also transferred to adult court.

“In the 1990s, virtually every state in the country, with the exception of only one or two, enacted legislation that made it easier to transfer kids to the adult system and some of these involved automatic transfers,” said Jay Blitzman, the former first justice of the Massachusetts Middlesex County Juvenile Court Division.

In some states, children were automatically transferred to adult courts based on their age and offense alone, said Blitzman, who teaches juvenile law at Northeastern University School of Law. “That system most adversely affected young people of color.”

The latest data from the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention show Mississippi is one of five states that allow 13-year-olds to be prosecuted as an adult. In Mississippi, a 13-year-old is automatically prosecuted as an adult if the crime involves the use of a deadly weapon or carries a life sentence.

Three states, Colorado, Missouri and Vermont, allow 12-year-olds to be tried as adults. And, two states, Iowa and Wisconsin, allow children as young as 10 to be tried as an adult.

Dilulio later admitted his well-publicized theory was a myth, but the damage had already been done.

“Between 1980 and 1993, the rate of life without parole per homicide arrest of a child was between one and two percent. By 1999, 11 percent of children arrested for homicide were sentenced to life without parole,” the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing report said. “Seventy percent of all youth ever sentenced to life without parole are people of color -- primarily Black and Latinx.”

The fear of super-predators and escalating crime rates in the 1990s also led to the elimination of parole for a large number of people in several states including Mississippi, de Gruy said.

In the mid-1990s, Mississippi lawmakers did away with parole for anyone convicted of a violent crime, he said. No exceptions were made for children. As a consequence, juvenile offenders convicted of first-degree murder or capital murder in Mississippi, both of which carry a life sentence, were automatically sent to prison for the rest of their lives. Judges had no discretion to impose a less severe penalty regardless of the circumstances of the crime.

Over the past 15 years, Marsha Levick, chief legal officer of the Juvenile Law Center, said she believes the U.S. Supreme Court has tried to move the country away from the extremely punitive penalties against children and back to the original intent of the juvenile justice system.

In 2005, the Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty for juvenile offenders. In 2010, it banned life-without-parole sentences for children convicted of non-homicide offenses. And, in 2012, in Miller v. Alabama, the court also banned mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles convicted of a homicide they committed when they were under the age of 18.

The court stopped short of banning all life-without-parole sentences for juveniles, but it said such harsh sentences should be reserved for the “rare” juvenile offender who is “permanently incorrigible” and cannot be rehabilitated. In 2016, the court ruled in the case of Montgomery v. Louisiana that Miller should be applied retroactively.

The court emphasized in Miller that children convicted of homicide offenses are less culpable than adults because of their “transient immaturity” and underdeveloped brains.

Justice Elena Kagan, who delivered the majority opinion in Miller, said “developments in psychology and brain science continue to show fundamental differences between juvenile and adult minds,” particularly the “parts of the brain involved in behavior control.”

As a result of Miller and Montgomery, juveniles convicted of a homicide – who were automatically sentenced to life without parole before Miller was decided and those convicted afterward – are entitled to a hearing to determine whether a life-without-parole sentence is appropriate.

While advocates are pleased the court banned mandatory life-without-parole sentences, they said judicial bias and racial disparities have increased since the Miller and Montgomery decisions, because judges now have more discretion.

Most juvenile offenders facing a sentence of life without parole in Mississippi and other states are not entitled to a jury at their sentencing or resentencing hearing. A judge usually determines whether they will be eligible for parole or die in prison.

“The Mississippi Supreme Court has ruled that (only) juveniles convicted of capital murder post-Miller have a statutory right, pursuant to Mississippi's capital murder sentencing statute, to be sentenced by a jury at their initial sentencing hearings,” said Jacob Howard, legal director of the MacArthur Justice Center in Mississippi.

“Oftentimes when we see discretion in the criminal justice system, it is used to penalize children of color,” Renwick said. Many judges still have “racialized misperceptions of Black boys” and “presume that Black teenage boys are irreparably corrupt,” she said.

“Of new cases tried since Miller, approximately 72 percent of children sentenced to life without parole (nationwide) have been Black — as compared to approximately 61 percent before Miller,” the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing report said.

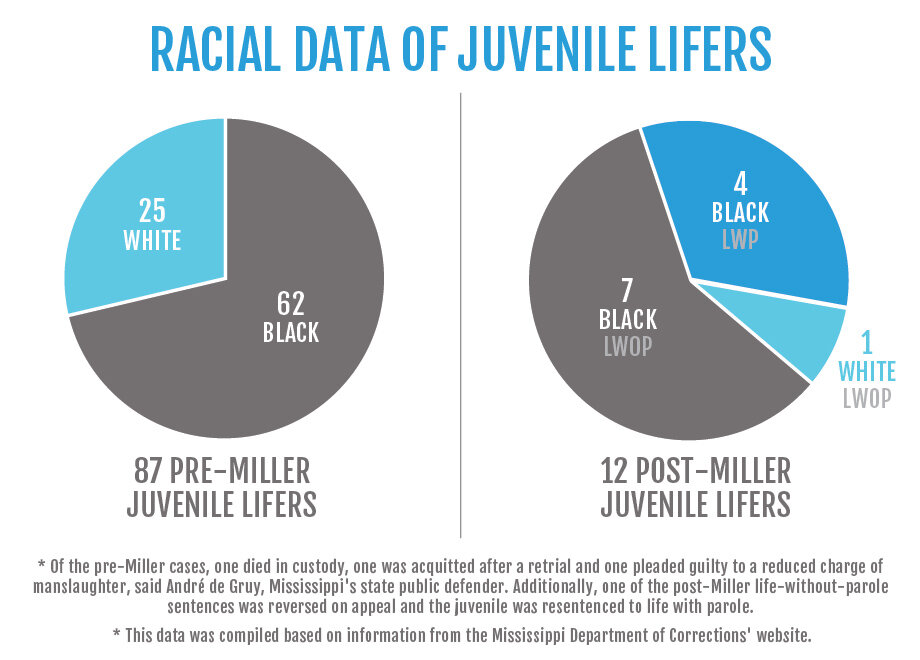

In Mississippi, eight of the 12 juveniles convicted of first-degree murder or capital murder since Miller have been sentenced to life without parole; all but one is Black. One sentence was reversed on appeal, and the juvenile was resentenced to life with parole. However, data from the state’s public defender’s office show that about an even number of Black and white juvenile lifers in Mississippi, who were serving mandatory sentences before Miller, have been resentenced to life without parole. This is largely due to the progressive treatment of juvenile offenders by district attorneys in Hinds County, which has had the most resentencings to date.

All juvenile lifers should have the benefit of a jury, Levick said, because oftentimes the judge overseeing the resentencing hearing is the same judge who presided over their trial. Thus, the judge may have difficulty “looking at these individuals for who they have become, not who they were when they committed the crime,” she said.

Blitzman, who represented youth accused of homicide during his 20-year career as a public defender before he became a judge, said every inmate should have an opportunity for parole, because “everybody changes over time. This is especially true for juveniles.”

“There is research now that shows that the more you detain, the higher the recidivism rate is going to be, and that’s just common sense,” Blitzman said, “because you are disconnecting people from the social networks that they will need. That is not to say that some people don’t have to be detained, the question is which ones and for how long.

“When you detain or incapacitate people for a long period of time, without any hope of release, you go past the point where there is any legitimate public safety purpose and the process then is purely retributive.”

This project was produced in partnership with the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Report for America corps member Shirley L. Smith is an investigative reporter for the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization that seeks to inform, educate and empower Mississippians in their communities through the use of investigative journalism. Sign up for our newsletter.

Report for America is an initiative of, and supported by, its parent Section 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization The GroundTruth Project (EIN: 46-0908502).