All Bundled Up During Black History Month? Remember The Black Man Who Was First At The North Pole

The Arctic has invaded the lower 48: The arrival of its cold air means that half of America is walking around dressed like the Inuit man on the tails of Alaska Airlines’ planes. During this Black History Month of record cold temperatures, let’s remember the Black member of Adm. Robert Peary’s expedition, Matthew Henson, the first man to reach the North Pole. Although the entire globe has been mapped, it’s still very exciting to read about the first men to travel anywhere unknown.

There were tragic incidents during exploration of the far North. But its history is not as bad as Antarctica’s. Arctic exploration didn’t involve spectacularly ill-fated voyages like Henson contemporary Ernest Shackleton’s, or deaths during races to the South Pole like British explorer Robert Scott’s. But it’s tragic that the first Black man to reach the North Pole, as part of Peary’s expedition in 1909, was overlooked for almost 30 years.

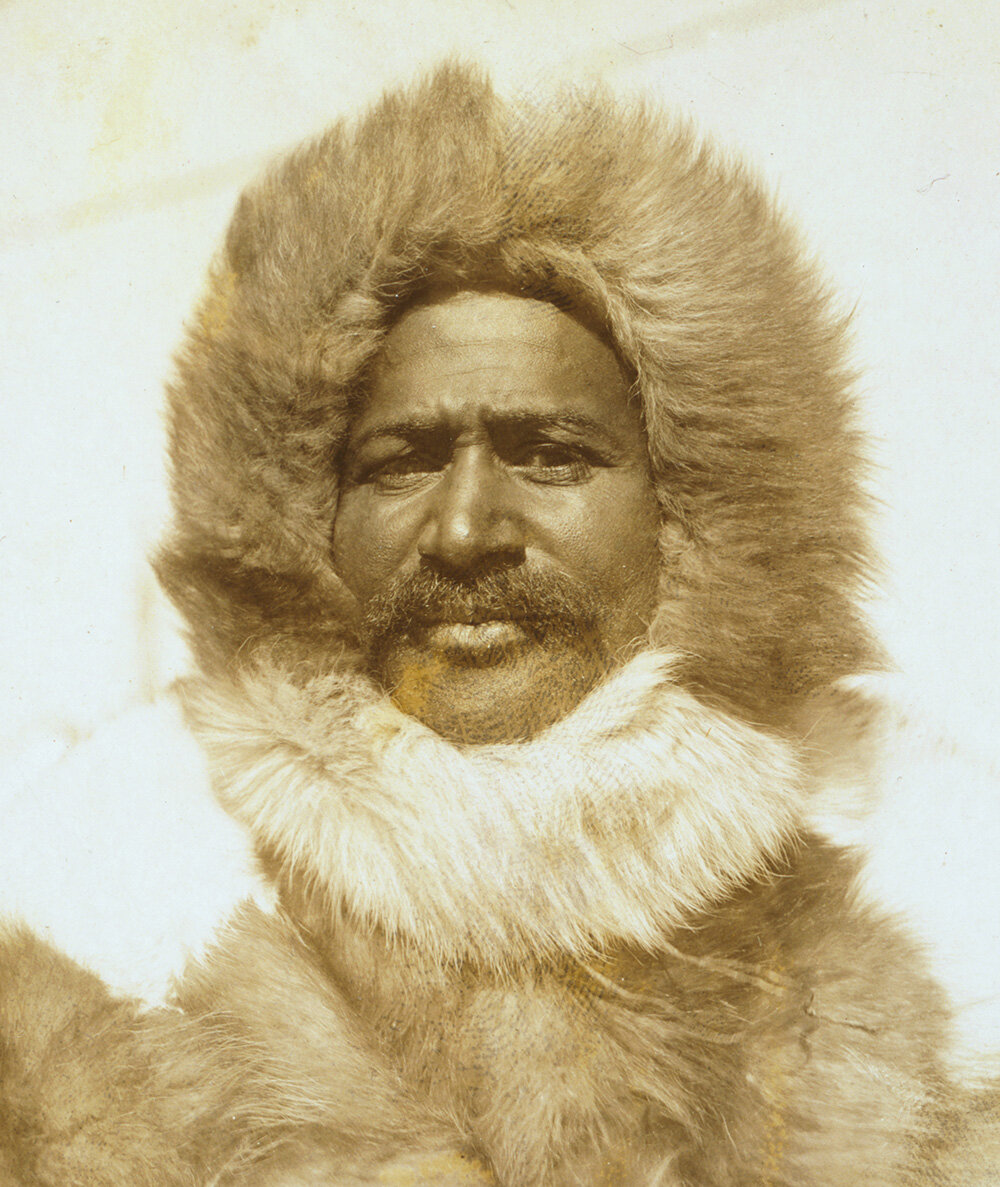

Matthew Henson was an American explorer who was among the first human beings to set foot on the North Pole. Wikipedia

Matthew Alexander Henson was born just after the Civil War, in August 1866 in Maryland, so he was very used to hot weather. His parents were free sharecroppers who were the descendants of slaves. A speech by Frederick Douglass, another Marylander, inspired Henson to seek life-long learning. Henson had an adventurous spirit: Orphaned at age 11, he walked to Baltimore and was hired as a cabin boy on a merchant ship at age 12. He went to sea for about six years, learning to read, write and navigate. He voyaged to Europe, Africa and Asia.

In November 1887, working on dry land at a Washington, D.C., clothing store, Henson met U.S. Navy Cmdr. Robert E. Peary. When Peary, a civil engineer, heard about Henson's seafaring experience, Peary hired him as an aide for his planned voyage and commission to survey Nicaragua. Fittingly, Henson was known as Peary’s “first man,” a navigator and craftsman.

From 1891 to 1909, the pair traveled and explored Greenland and the Arctic, making seven expeditions before they were able to reach the North Pole. Their first Arctic expedition was 1891 to 1892. Like Peary, Henson learned the Inuit language and studied and imitated how the Inuit survived in the icy wastes and winds. He learned to build and live in igloos, and wore a loose sealskin parka that allowed sweat to evaporate without chilling him. The Inuit remembered Henson as the only non-Inuit who could build a sledge, mush on through the snow behind dogs and train dogs to pull sleds the Inuit way.

In 1905, Peary and Henson, backed by President Theodore Roosevelt, sailed a then state-of-the-art vessel that could cut through ice. Their ship sailed within 175 miles of the North Pole. But there melted ice blocked their passage and forced them to turn back.

After six failures to reach the Pole, now-Rear Adm. Peary and Henson set out once again in 1908. Several members of the expedition turned back. Peary wrote that he would never make their goal without Henson. In April 1909, the two finally arrived at the North Pole, despite the unforgiving cold and the feeling that snowflakes on their eyelashes had frozen their eyes shut, if only momentarily. Henson said, “I think I’m the first man to sit on top of the world.”

Henson was popular with natives and with Peary’s crews. In 1912, Henson published a memoir, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole. “I have come to love these people,” Henson wrote of the Inuit. “They are my friends and regard me as theirs.” On the final page of his memoir, Henson recorded all 218 names of the Inuit from Smith Sound on Canada’s Ellesmere Island.

Peary received many honors, but his expedition was heavily criticised and dismissed because it included a Black man. How could a Black man have measured the pair’s position properly and verified that he and Peary actually had reached the North Pole? When Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen became the first man to reach the South Pole in 1911, and then the North Pole in 1926, he carefully checked and double-checked his positions to avoid the criticisms that had targeted Peary and Henson.

Henson continued to be overlooked, so much so that he and Peary had a falling out. Late in his life, in 1937, at age 70, Henson finally was inducted into the elite Explorers’ Club. In 1944, he and other members of the expedition were awarded Congressional Medals for polar exploration. Along with Peary, Henson and his wife are buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

As you stagger through the winds and blizzards afflicting half the country this week, remember Henson and Peary and be glad we’re not at the North Pole — we just look and feel as though we belong there.

Ann Marie Cunningham is a Columbia University Lipman Fellow for 2020 who will be working with the Mississippi Center for investigative Reporting. She is a veteran journalist/producer and author of a best-seller. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Technology Review, The Nation and The New Republic. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.