When Young Love Stops Being Romantic

Tenaj Moody, 27, is a striking and stylish young woman who has earned a master’s in criminal justice and behavior, as well as her license. Starting in 2014, when she was a college freshman, she began speaking publicly about abuse she suffered from her high school boyfriend. She was in demand because 50 percent of college women are subjected to some form of dating abuse. Moody launched her own small consulting business, Light to Life LLC, whose mission is to stop dating abuse as well as domestic violence. Today, she frequently speaks at high schools, colleges and universities, juvenile justice facilities and elsewhere, and she has two podcasts on which she talks to young women.

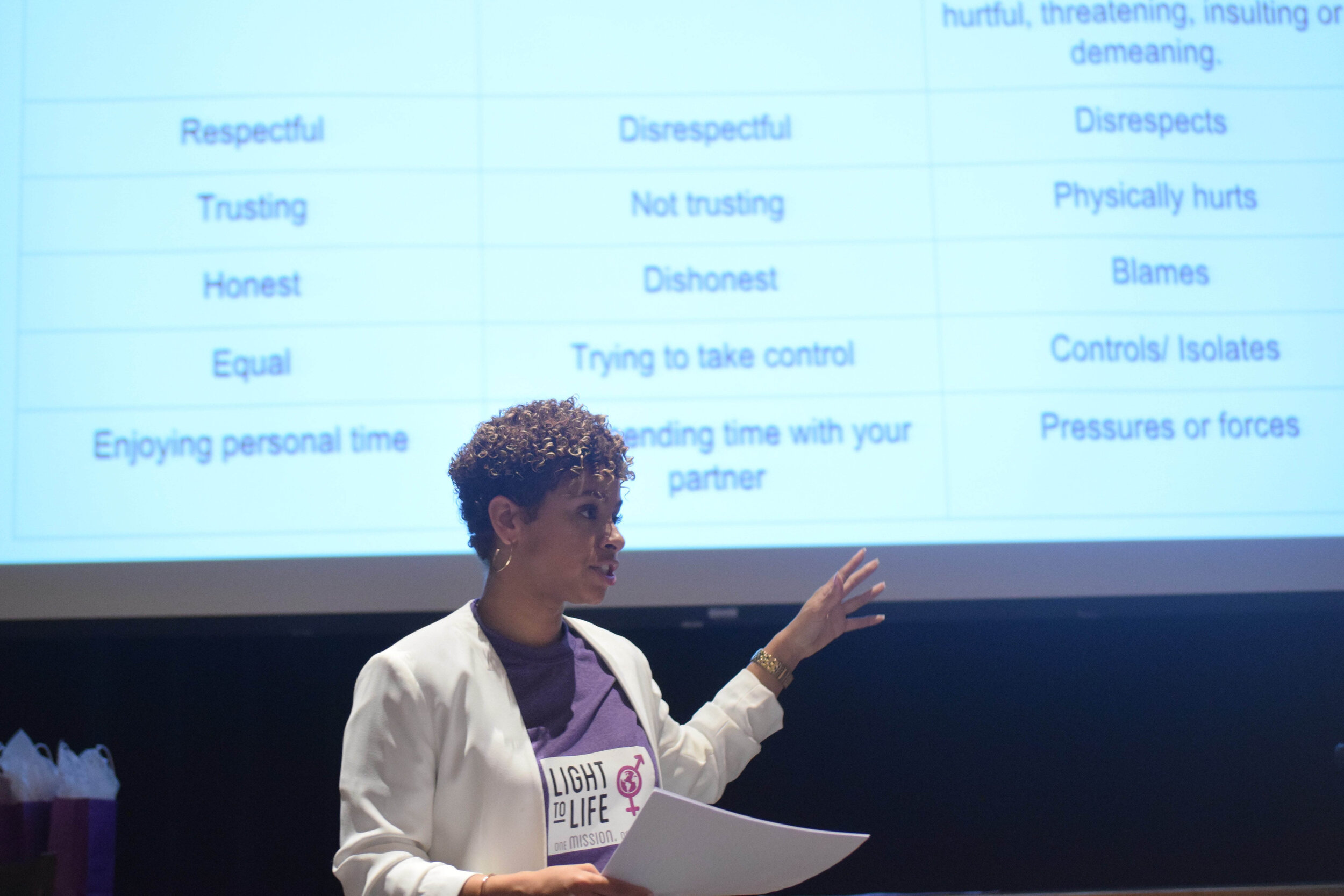

Tenaj Moody, seen here during a recent public presentation, founded the small consulting firm Light To Life LLC to stop the kind of dating abuse and domestic abuse she fell prey to in high school. She frequently speaks to high school and college students to inform young, inexperienced women about warning signs of future trouble. Photo courtesy of Tenaj Moody

To inform young, inexperienced women about warning signs of future trouble with someone they’re dating, Moody likes to tell her own story. She grew up in north Philadelphia, the daughter of a single mother who was incarcerated 18 times while Moody was growing up. Besides poverty and sometimes homelessness, Moody became acquainted with her mother’s abusive partners. Exposure to domestic violence can mean that a young girl is likely to become a victim herself, while a boy may become an abuser. They begin playing those parts in what they believe are normal human relations.

In high school, as a 16-year old freshman, Moody met “an older man,” an 18-year old junior. She fell hard: “I thought he was the love of my life. You know that feeling when you get excited because you hear his name?”

The relationship continued for three years, until the end of Moody’s senior year, when she found herself in court. Her boyfriend had charged her with assaulting him; she says she was protecting herself against his attempts to kill her. Moody’s mother paid a fine for her, and she had to do community service: “It was a classic case of blaming the victim.”

Those three years certainly were not non-stop abuse, Moody emphasizes. “I loved him, but I reached a breaking point.” There were plenty of red flags, but they started quite small. At first, her boyfriend didn’t want her texting male friends. He didn’t want her in touch with men he didn’t know; he didn’t even want one of his good friends putting his arm around Moody. Soon he was forbidding her to wear shorts to school; she had to return home and put on sweatpants. He began telling her “who I could and could not hang with, and he didn’t want me spending time with my family.” All this monitoring, Moody points out, erodes a victim’s self-esteem and confidence.

“Watch for a pattern of behavior like this,” Moody advised. “If you get upset, he apologizes, and then the cycle starts all over again.” Love Labyrinth, a short video, illustrates what Moody describes. It was produced by One Love Foundation, a nonprofit founded in honor of a 22-year old college student beaten to death by her ex-boyfriend, just three weeks before her graduation.

Throughout the abuse, Moody did have someone at her back: her mother, an activist and survivor, who recognized that something was wrong. Her mother made an appointment for her daughter with a therapist. Moody’s boyfriend came to pick her up and grilled her about the session. As she maintained that she had told the therapist nothing about him, he punched her hard in the left side of her head. Even as her face swelled, he was apologizing: “I don’t want this woman to break us up.”

After another physical assault, Moody and her mother had to go to court. By that time, Moody couldn’t speak; her mother did all the talking.

Moody is working hard to prevent things going this far for other young women. “Trust your gut. It will let you know if something he does is not right.” She especially warns about digital abuse, to which her younger audiences are particularly susceptible. For more about apps that can help fight back, see the National Network to End Domestic Violence’s resources.

Ann Marie Cunningham is a Columbia University Lipman Fellow for 2020 who will be working with the Mississippi Center for investigative Reporting. She is a veteran journalist/producer and author of a best-seller. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Technology Review, The Nation and The New Republic. Contact her at amclissf@gmail.com.