Why Do Some Black Men Abuse Women?

Black women suffer from domestic violence out of proportion to their slice of the American population, a bit less than 7 percent. The problem is so striking that the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence devoted their 2020 annual meeting, held online, to violence against Black women. Most of these women know the men who beat them; they are their husbands or intimate partners. That means that these Black men are abusers. What makes them abusive towards loved ones?

Two Black authors have written acclaimed memoirs that detail abuse they suffered, mainly at the hands of their own mothers. Both were raised by single mothers. One man turned against himself, in the form of eating disorders and a gambling habit, and says he was abusive to women mainly by lying to them and stealing from them. The other man admits he has been physically and verbally violent toward women, says in another memoir that he is capable of relapsing, and works to educate other Black men about violence towards women and violence in general. Both men remain very loyal to their mothers and maternal family.

Kiese Laymon, a professor of creative writing at the University of Mississippi, wrote a 2018 memoir Heavy.

Kiese Laymon, now a professor of creative writing at the University of Mississippi, wrote his 2018 memoir, Heavy, in the form of a book-length letter to his complicated mother. Born in rural Mississippi but determined to get an education, she carried him in her backpack to her classes at historically Black Jackson State University in Jackson. She became a professor of political science at Jackson State and, Laymon writes, collected books even if the two didn’t have much to eat. “The presence of all those books...and your insistence I read, reread, write, and revise in those books, made it so I would never be intimidated or easily impressed by words, punctuation, sentences, paragraphs, chapters, and white space.”

His mother also had an abusive longterm boyfriend. In the 1980s and 1990s, beginning when Laymon was 9 or 10 years old, she beat her young son regularly with a belt for behavior she thought would disgrace him with whites. While he was at a largely Black parochial school, she did not bother to hit parts of his body where the welts would be invisible; when he transferred to a largely white school, she did.

Sometimes she beat him for listening to hip-hop. More often, she beat him for misbehaving, syncing her strokes to her words, “don’t … you … know … white … folks … don’t … care … if … you … die …” His friends knew what she did, because they were beaten, too: “We figured it was our mothers’ way of keeping us out of Black gangs, Black prisons, Black clinics, Black cemeteries.”

Mother and son kept divisive secrets from each other. Even after Laymon had become a college professor, his mother never confessed that she had a gambling habit. Until Heavy was published, he never told her he’d been sexually abused by a babysitter.

Even as a child, Laymon was a binge eater. As a professor, he starved himself and over-exercised until his body rebelled and broke down. For about six years, he gambled and lost compulsively. He has damaged himself physically and financially, and has yet to marry. He’s a professional success, who has damaged himself in a professional manner.

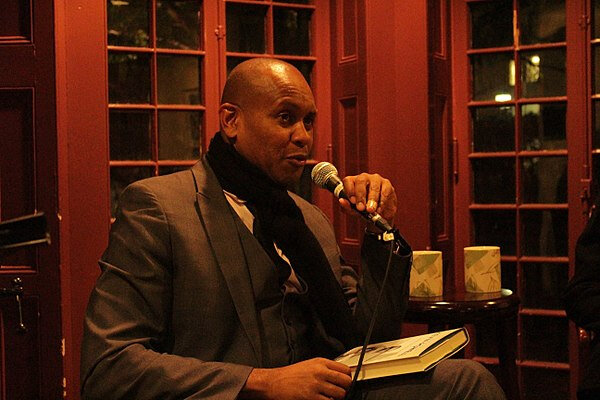

Kevin Powell, a well-known activist, speaker and author of 14 books, seen here speaking at a November 2015 event, has written an acclaimed memoir that details abuse he suffered, mainly at the hands of his single mother and how that led him to be verbally and physically abusive to his girlfriends and other women.

Eight years older than Laymon, Kevin Powell also is a well-known activist, speaker, and writer, the author of 14 books who grew up very poor in Jersey City, New Jersey. His mother, very different from Laymon’s, never pursued her own education. Burdened with rules and superstitions from rural South Carolina’s Low Country where she grew up, she never worked for more than minimum wage. Her father beat her, her siblings and her mother, sometimes with his fists, sometimes with a mule whip or a soda bottle.

When Powell was only three, his mother sat him down and told him, “You are going to college ...You have to go farther in school than I did … Get you a good education and you can get you a good job. You can be somebody.” Later she got him a public library card, and never protested his non-stop reading.

His mother told him he was “smart,” but never gave him any hugs or kisses. She did to him what had been done to her: “My mother beat me for as long as I can remember. She used her hands, one of my belts, or ‘a switch,’ a long, flexible type of wood yanked from bushes in our ‘hood” that “caused the most damage — inflamed welts would rise on my arms and legs.” Sometimes she beat him in public: in front of party guests when he was 4 because he had vomited, when he was older in a department store for wandering away and in front of a school official who said he had misbehaved. No one ever intervened.

Like Laymon’s mother, Powell’s mom had a litany “repeated as each blow landed: ‘You gonna be good? You gonna be good?’” Powell writes that her refrain “gave me nightmares that still haunt my sleep.”

Small wonder that Powell remembers often being an angry child. He went on to sabotage opportunities with his anger, to become violent and verbally abusive towards his girlfriends and other women. Today he lectures on sexism and misogyny, and in a book he edited, The Black Male Handbook, he contributed a chapter on ending violence towards women and girls.

Both of these books are terribly sad. My heart broke for 4-year old Kevin, beaten publicly for throwing up because adult party guests gave him alcohol, for 19-old Kiese, having his mother pull a gun on him and throw him out of the house for talking back. Both books make enormously clear that Laymon and Powell both grew up in households where they were taught that violence was normal. At the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence annual conference, some women talked about the importance of reversing that lesson and referring other women to anti-spanking organizations and EndHitting USA.

In Australian investigative reporter Jess Hill’s book, See What You Made Me Do, she describes a rehabilitation group for abusers that works because it focuses on the shame they feel at the bottom. Both Laymon and Powell have done a service by laying bare that shame and making it believable and understandable.

Ann Marie Cunningham is a Columbia University Lipman Fellow for 2020 who will be working with the Mississippi Center for investigative Reporting. She is a veteran journalist/producer and author of a best-seller. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Technology Review, The Nation and The New Republic. Contact her at amclissf@gmail.com.