Will the Violence Against Women Act Go On Saving Lives?

The Violence Against Women Act, first passed in 1994, makes possible local advocates’ ability to prevent and respond to domestic violence, sexual assault, dating violence and stalking. Up for reauthorization in 2021 is an updated, stronger VAWA, with important improvements based on feedback from service providers and program beneficiaries.

As intimate-partner violence and child abuse have spiked during the pandemic, VAWA and other advocates for victims also worked for more funding for culturally specific resources. The new, improved VAWA already got the House’s thumbs-up in 2019. Small wonder: The House has a Bipartisan Task Force to End Sexual Violence that also deals with domestic violence. The co-founder and co-chair, Rep. Ann McLane Kuster, R-N.H., has been open about her own history of sexual assault.

The House also has a Bipartisan Working Group to End Domestic Violence. Two of the three cofounders, Working Group leaders Reps. Debbie Dingell, D-Mich., and Gwen Moore, D-Wis., have been public about their experiences with domestic violence and in Moore’s case, sexual assault.

Another member of Congress, Rep. Lizzie Fletcher, D-Texas, recalled the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on the Capitol in an interesting way: “The idea that we should just ‘move on’ remains the most terrifying to me. Many, many years ago, I volunteered at a domestic abuse shelter, and it felt like people kept saying, ‘Don’t impeach the president or it (assault on the Capitol) might happen again.’ That’s just the language of abuse.”

After the House had reauthorized VAWA and passed it to the Senate, said Capitol Hill staff who spoke on background, this essential legislation was interred in “Mitch McConnell’s graveyard” for bills he and President Trump did not like.

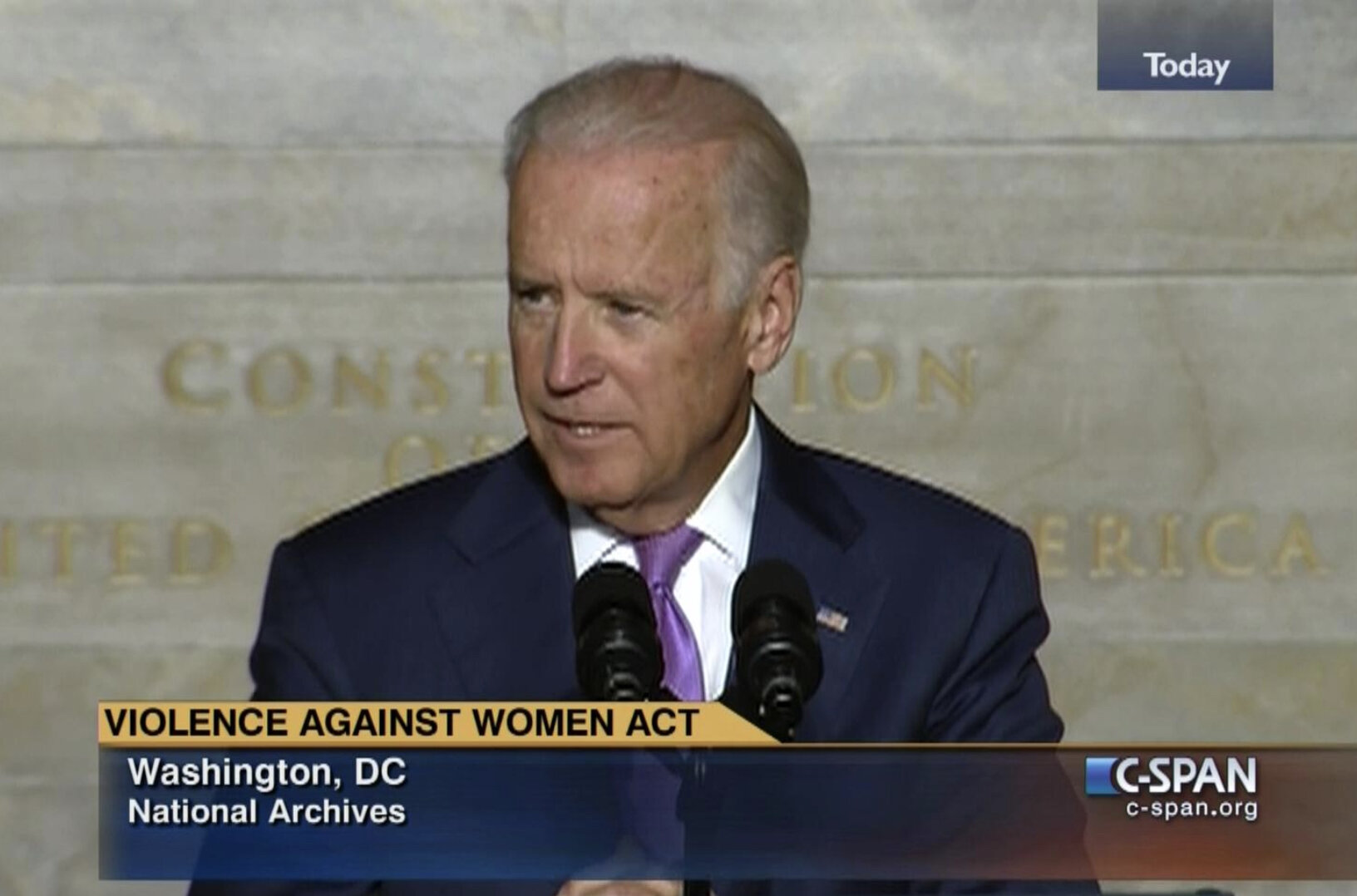

During the 2020 presidential election, VAWA reauthorization was a plank in the Democratic Party platform. Now President Biden, who was one of VAWA’s original co-sponsors when he was a senator from Delaware back in 1994, has included Senate reauthorization in his agenda for his first 100 days in office.

Then Vice President Joe Biden, a primary sponsor of the Violence Against Women Act when he was a U.S. senator, speaks at the National Archives in 2014 honoring the act's 20th anniversary. C-SPAN

How has VAWA changed? Rep. Moore noted that when Congress reviewed the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act, she and other members found there weren't adequate protections for LGBTQ women, women of immigrant status and Native American women. Alaskan indigenous women were ignored completely, despite Alaska’s high rate of domestic violence.

In Oakland, California, lawyer Grace Huang, policy director of the Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence who co-chairs the Alliance for Immigrant Survivors, worked with Rep. Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., to strengthen protections for immigrants from Pacific islands and Asian countries. Often abusers use the threat of deportation to control victims. Many victims aren’t married to their abusers, but have been forced into sex work or labor without pay. Huang and other advocates also worked for more funding for culturally specific advocates for victims

During reauthorization in 2013, Moore championed a very important change in VAWA, according to lawyer Mary Kathryn Nagle of the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center. In 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Oliphant Decision had determined Native American nations didn't have criminal jurisdiction over non-Indian perpetrators. Non-Indian men who raped or abused Indian women were not subject to tribal courts, and hence could act with impunity on tribal land. Subsequently, Chief Justice William Rehnquist left the issue up to Congress.

Moore made sure that amendments added to VAWA strengthened protections for Native American women as well as Alaskan Native, Eskimo and Aleut women, who had been overlooked completely. Now any non-indigenous individual who abuses an indigenous woman on tribal land would be held accountable in tribal court. Conservatives concerned about tribal courts’ overreaching their authority asked Moore to cut these additions. But she maintained, “We're not giving up Native women in order to pass this bill.”

Now that VAWA’s reauthorization is up to the Senate, will Moore —and Biden — get their way? Will the Senate pass the new, stronger VAWA? Both of Mississippi’s senators are Republicans. Senior Sen. Roger Wicker voted for reauthorization in 2013. The first woman to represent Mississippi in Washington, D.C., Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith has been in Congress only since 2018.

Since Biden is one of the two original authors of VAWA, the bill is his baby. Today marks the 43rd day of his administration. According to Hill staff, few senators understand the issues that VAWA is meant to address. Sen. Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, who said in 2019 that she is a survivor of rape and domestic violence and who has advocated for sexual assault victims in the military, has tried to introduce her own version of VAWA. Sen. Hyde-Smith did not support it because of “concerns from constituents.”

However, Hill staffers doubt McConnell will spend any political capital calling a filibuster to block VAWA. Filibustering against women’s safety from intimate-partner violence? How unflattering does that sound?

Ann Marie Cunningham is a Columbia University Lipman Fellow for 2020 who will be working with the Mississippi Center for investigative Reporting. She is a veteran journalist/producer and author of a best-seller. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Technology Review, The Nation and The New Republic. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.