Back to School Special: Who First Challenged School Segregation in Mississippi?

As elementary and high school students in Mississippi head back to school this month, they may not consider themselves lucky, but they are: The landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, which desegregated public schools, did not take effect in Mississippi until 1970. But today, any Mississippi student can go to public school, regardless of race, creed or color.

In 1924, one father of a daughter about to start middle school found that was not the case. Three decades before Brown v. Board of Education, he decided to fight. Mississippi’s Asian population is growing, especially in Flowood outside Jackson, so it’s high time to honor Jeu Gong Lum – particularly given the continuing violence against Asian Americans all over the U.S.

The Gong Lum family of Rosedale, Miss., filed the first federal lawsuit to integrate schools. Ann Marie Cunningham/MCIR. Photo courtesy of the Lum family for the book,‘Water Tossing Boulders’

Gong Lum was an upstanding Chinese immigrant who owned a grocery in the Delta school district of Rosedale. In 1924, his older daughter, Martha, was ready for middle school. In her way was the 1890 Mississippi state constitution, which said “separate schools shall be maintained for children of the White and colored races.”

Gong Lum and other Chinese men arrived in Mississippi because of a labor shortage. Chinese men first began coming to the United States in the 19th century, to build railroads and mine gold. Any Chinese women usually were trafficked; Chinese laborers could not bring their families. After the Civil War ended in 1865 and railroads were completed in 1869, Mississippi plantations needed labor. Black sharecroppers were making the Great Migration in droves to cities in the North, East, and West. A Vicksburg newspaper advocated a solution: recruiting “the Coolies.”

Between 1882 and 1920, more than 17,000 Chinese men were smuggled into the U.S -- along with drugs and liquor--from Mexico and Canada. One of these men, Jeu Gong Lum, made his way over the Canadian border to the Mississippi Delta, home to about 1,200 Chinese. Illegal Chinese felt safer in the seven thousand square miles of the rural Delta than they did in crowded cities.

Chinese workers quickly became disillusioned with working conditions and pay on plantations. Most of them were sending money home to their families in China. From a culture that advocated entrepreneurship rather than working for others, Chinese men in the Delta opened grocery stores that catered to Blacks. Sharecroppers spent what little cash they had on food, so Chinese grocers prospered. Blacks liked them because they allowed customers to use their stores as social clubs, and did not require the same elaborate courtesy that Jim Crow mandated from Blacks towards Whites. In 1955, 14-year old Emmett Till was murdered because he had been considered impolite to Carolyn Bryant in her husband’s grocery in Money in the Delta.

Through other Chinese who had emigrated to the Delta, Gong Lum met and married Katherine Wong, an American citizen, in 1912. The couple opened a small grocery store in the plantation town of Benoit. They had two daughters, and then a son.

Katherine Gong Lum, photographed here about 1915, holds her daughters Martha, left, and Berda, who inspired the family’s lawsuit. Photo courtesy of the Lum family for the book, ‘Water Tossing Boulders’

When their older daughter, Martha Lum, was old enough to go to middle school in the Rosedale school district, she couldn't. Jim Crow ruled Mississippi, and Chinese were considered "colored." A very few Delta towns had set up separate schools for White, Black, and Chinese children, but Rosedale could not afford a third school.

Gong Lum was an unusually brave man. At the time, most Chinese immigrants were cynical about the legal system in their native country, and frightened of the way the law in Mississippi treated Blacks. Nevertheless, Gong Lum sued to integrate Delta schools.

In 1924, Gong Lum v. Rice went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled against them in what has been called the court’s most racist decision. The Court, which regularly struck down any desegregation cases, upheld the Mississippi state constitution and asserted that Chinese are not “White” and had to be classified as among “colored races.” One of the justices, Louis Brandeis, had been raised in Kentucky and supported segregation.

In order to educate his daughters, Gong Lum sent them to relatives in Chicago. The girls were treated badly there, even though Gong Lum had helped his cousin set up his own laundry business. His daughters were immigrants again, from the South to a Northern city where they had more in common with Blacks from the South than with Whites or Chinese students. Katherine retrieved the girls, and the family moved to Arkansas, where the children were able to go to school with Blacks.

You won't read about Gong Lum v. Rice in history books, their younger daughter Berda explained, because “we lost.” If you’d like to learn more about how one family of Chinese immigrants led the first battle to integrate American schools, you can consult Water Tossing Boulders by Adrienne Berard, and The Mississippi Chinese: Between Black and White by James W. Loewen.

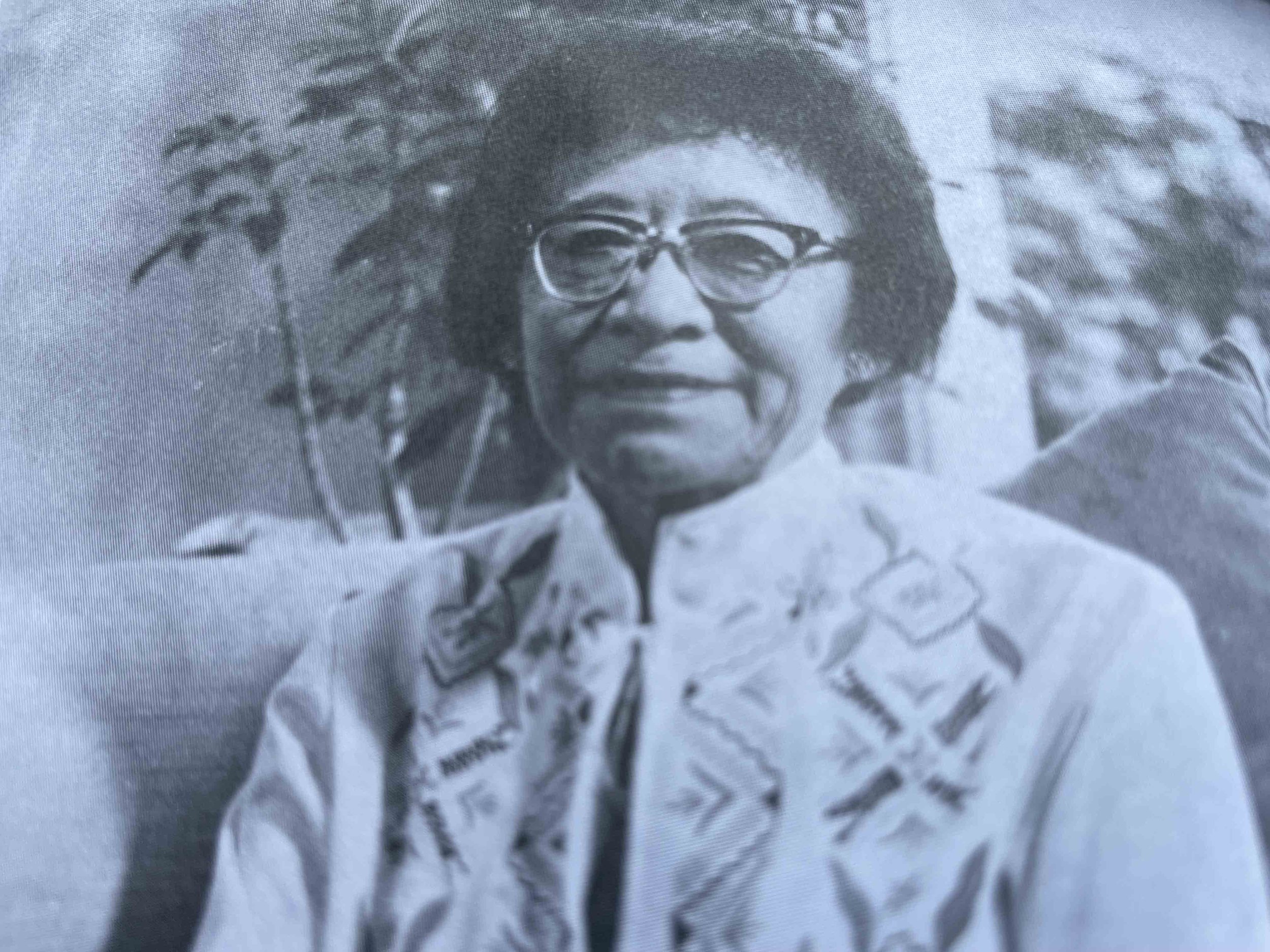

Berda Lum Chan, Gong Lum's younger daughter, is pictured in later life in Houston, Texas. She died in 1994. Third World Newsreel/National Endowment for the Humanities

Ann Marie Cunningham is MCIR’s Reporter in Residence. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.