What Is It Like to Be Jewish in Mississippi?

The High Holy Days, the most sacred days in Judaism’s calendar, began at the end of September. In New York, the largest Jewish community in the world, everything stops. In Mississippi, there have never been many Jews, and recently, Jewish communities have been dwindling.

Before and after the Civil War, Mississippi had a small population of Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jewish immigrants from Europe. Many had arrived in New Orleans, and made their way up the Mississippi River. They roamed the state as peddlers, until they had enough capital to open stores and other small businesses. They were loyal to the Confederacy, their new home, and fought and died in the Confederate army.

The cover of Robert N. Rosen's book The Jewish Confederates, published in 2000. Ann Marie Cunningham/MCIR

Robert N. Rosen, a lawyer in Charleston, South Carolina, describes in his book The Jewish Confederates the era when Reb Jonathan signed up to be Johnny Reb. According to Rosen, more than 200 Jewish Mississippians fought in the Confederate States army.

One reason some Jews remained loyal to the point of wearing Confederate gray is that the Confederacy was not anti-Semitic. Judah P. Benjamin, a prominent Louisiana planter and slave owner, was elected to the U.S. Senate and held various cabinet positions in the Confederacy, including secretary of war and secretary of state.

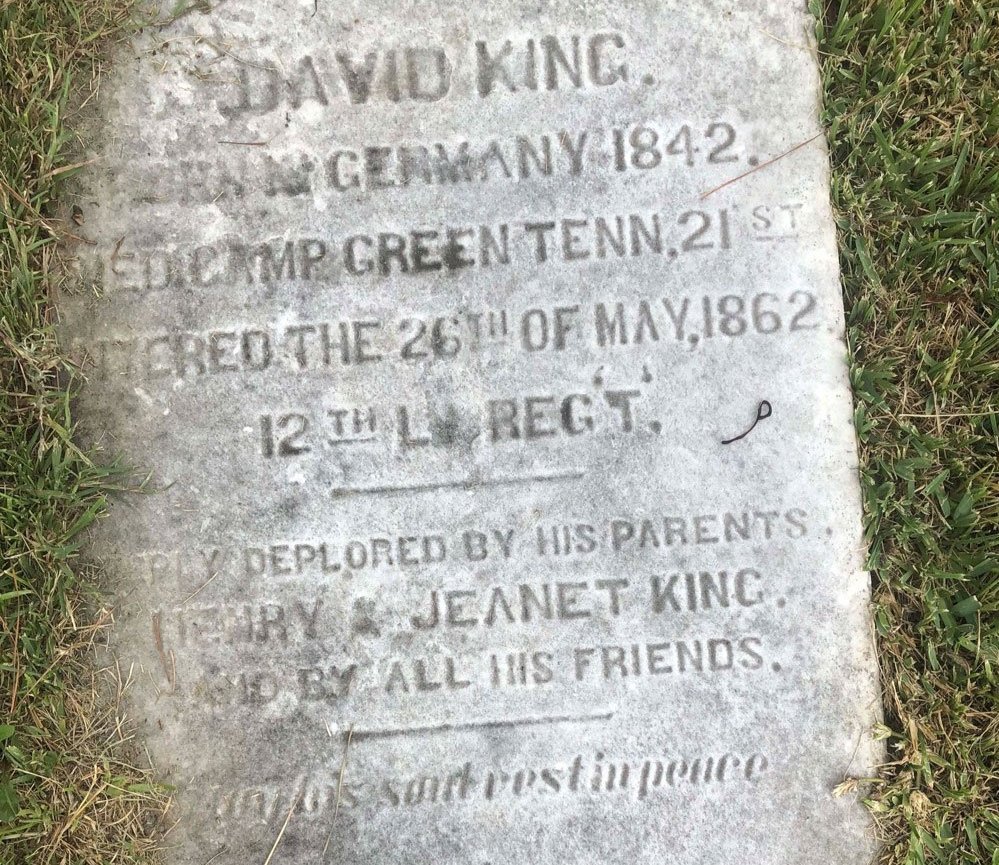

In Mississippi, Beth Israel, still the sole synagogue in Jackson, opened its cemetery on State Street in 1860. Among the graves from the Civil War is that of Confederate Pvt. David King, who died at an army camp in Tennessee. His gravestone is inscribed, “Deplored by his family and all his friends.” Some of my students think that Private King himself is being deplored, perhaps by abolitionist acquaintances and relations, for taking the Rebel stand. But it is more likely his gravestone’s inscription deplores his death, and his friends and family agreed with his loyalty to the Confederacy.

Pvt. David King of the Confederate States Army lies in Beth Israel cemetery in Jackson. Ann Marie Cunningham/MCIR

After the Civil War and the founding of the Ku Klux Klan, the atmosphere for Jews in the South changed enormously. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, White Protestants revived the Ku Klux Klan near Atlanta. In addition to Blacks and other people of color, the Klan targeted Jews and Catholic immigrants.

In Jackson at the height of the civil rights movement in the early 1960s, Rabbi Perry Nussbaum was an outspoken proponent of civil rights and antiracism. He was a chaplain for Freedom Riders who were imprisoned and helped raise money to rebuild Black churches that White supremacists burned down or bombed. In 1967, the Klan bombed Nussbaum’s house and then two months later, Beth Israel Congregation itself. The synagogue has moved several times, but the cemetery remains in its original location on State Street.

Today, Mississippi’s Jewish population is shrinking. In smaller communities like Greenville, older congregation members are slowly dying, and younger members aren’t replacing them.

But interest in Judaism remains strong in the South. Macy B. Hart is founder and president emeritus of the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, where I researched Private King. In 1986, Hart also founded the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience; a new one opened in New Orleans late last year.

Beth Israel’s congregation includes James E. Bowley, a Millsaps College professor of religious studies and department chair, who holds a shabbat service on campus every Friday at 4 p.m. At the special Rosh Hashanah shabbat on Sept. 30, most of the dozen or so attendees were not Jewish – one was Hindu and one was a Chinese Communist – but religious studies students or simply interested parties who wanted some wine, hallah, honey and apples.

Another Beth Israel member is Mindy Humphrey, who raised her two sons in Jackson. She says that as a Jewish woman, she doesn’t feel ignored. “It's just that people don’t know. They’ll say things like ‘You’re a good Christian woman.’ I’ll mention my synagogue or my temple, and they’ll reply, ‘Oh, your church.’”

Mindy’s older son, Sam, 30, runs his organic vegetable farm, Fertile Ground Farm, within Jackson’s city limits. He attended the Henry S. Jacobs Camp in Utica, Mississippi, which opened in 1970 and where Macy B. Hart was director for 30 years. Young Jewish campers like Sam can go as soon as they start school. The camp strives to instill a Jewish identity in youthful Southerners.

Mindy Humphrey helps out at her son Sam's Fertile Ground Farm booth at Jackson Farmers Market. Ann Marie Cunningham/MCIR

Sam says the camp succeeded with him: He meets his Jacobs Camp friends every New Year’s Eve to celebrate together in Denver. He and his Jacobs Camp friends also have a fantasy football league they’ve dubbed the “Jew-Tang Clan.” Ask Sam and Mindy who’s winning when you visit Fertile Ground Farm’s booth on Saturdays at Jackson Farmers Market on the state fairgrounds.

Ann Marie Cunningham is MCIR’s Reporter in Residence. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.