Missing the 2021 Mississippi Book Festival? Try Visiting the Home of Jackson's Most Famous Writer

Eudora Welty, supreme 20th-century master of the short story, author of novels and essays, and winner of a Pulitzer Prize, spent almost all of her writing life in her family home in Jackson’s Belhaven neighborhood. When I first learned about her, I imagined her sitting on the front steps of a modest house like the Finch family’s in the film version of To Kill A Mockingbird. I was very wrong.

The front of Welty's house at 1119 Pinehurst in Jackson faces Belhaven University across the street. Welty scholar Michael Pickard calls it "a tether to identity" for Welty and "a companion to her late autobiographical works, The Optimist's Daughter and A Writer's Beginnings." Photo by Tom Beck courtesy of MDAH

If you’re exploring Belhaven on foot, tourists are likely to ask you for directions to the 1925 Welty house and gardens on Pinehurst Street. Welty’s father built the house across from Belhaven University, so the views always would be green. The house’s broad, tall, impressive stucco and wood Tudor facade is nothing like anything you glimpsed in To Kill A Mockingbird. Neither is the three-level garden, including Welty’s mother’s beds of roses on the second level, and at the bottom, what Welty called a “penthouse,” a small cabin where she and her two brothers played records, entertained friends and took joke photographs. They show that in the 1920s, Welty was a tall, attractive teenage flapper.

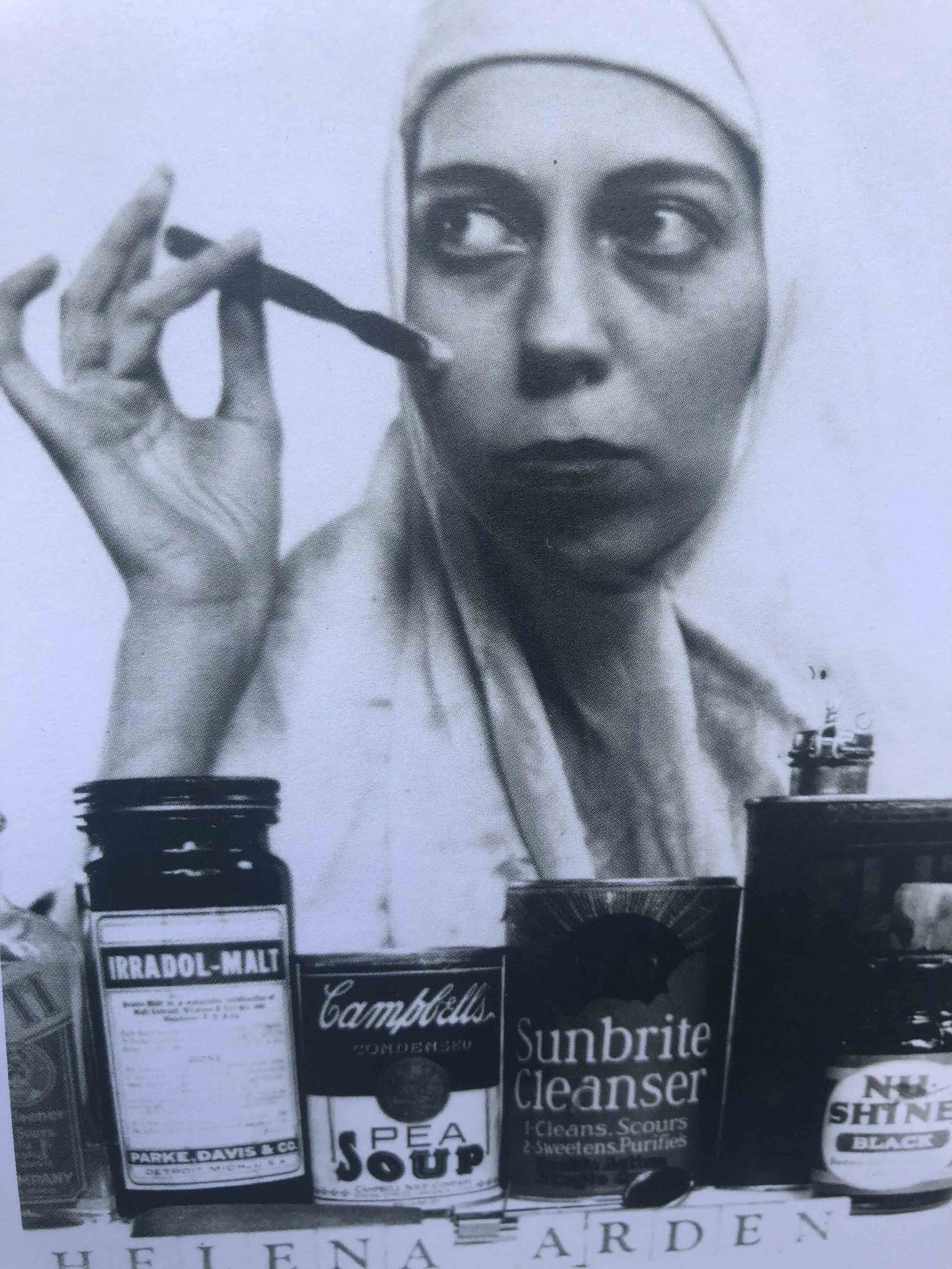

Welty loved photography, from either side of the camera. Here is a photo of a photo, produced in the small hideaway behind her family house, of Welty posing for a “Helena Arden” cosmetics ad.

My favorite photo is Welty as a makeup model, spoofing beauty ads by using household cleaning products and a toothbrush for application. I have used a postcard of this photo as a writing prompt, and when students leave my classroom, that postcard always disappears with one of them.

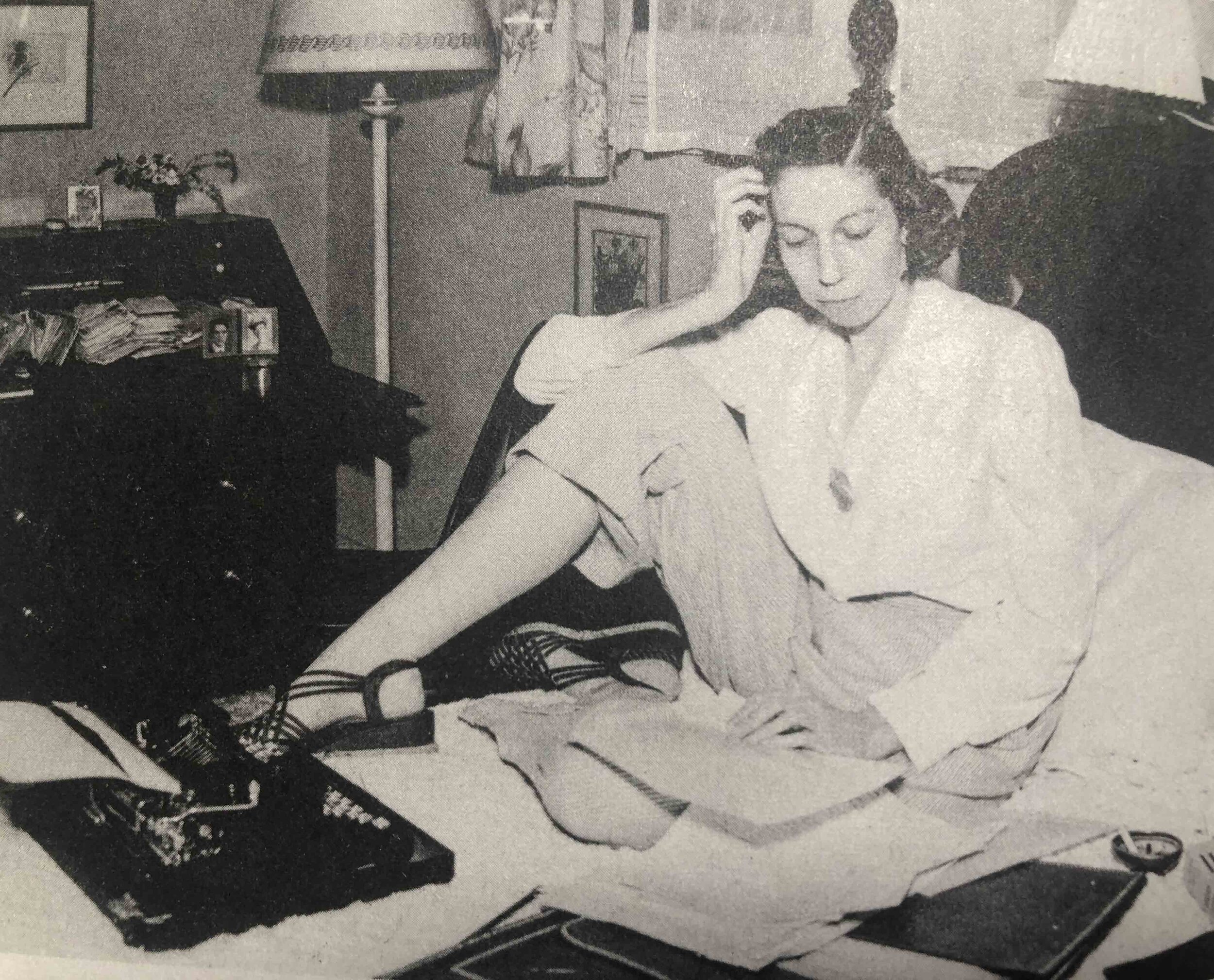

Another popular photo from the 1940s shows Welty writing on her bed, wearing slacks and sandals and hedged in by a full ashtray, books and notebooks, and a typewriter. That bed still stands in her bedroom. She had the most spacious and well-lit bedroom in the house, because she was the family’s only daughter. Today, the bedspread shows no tracks from the soles of those sandals or burn holes from those cigarettes.

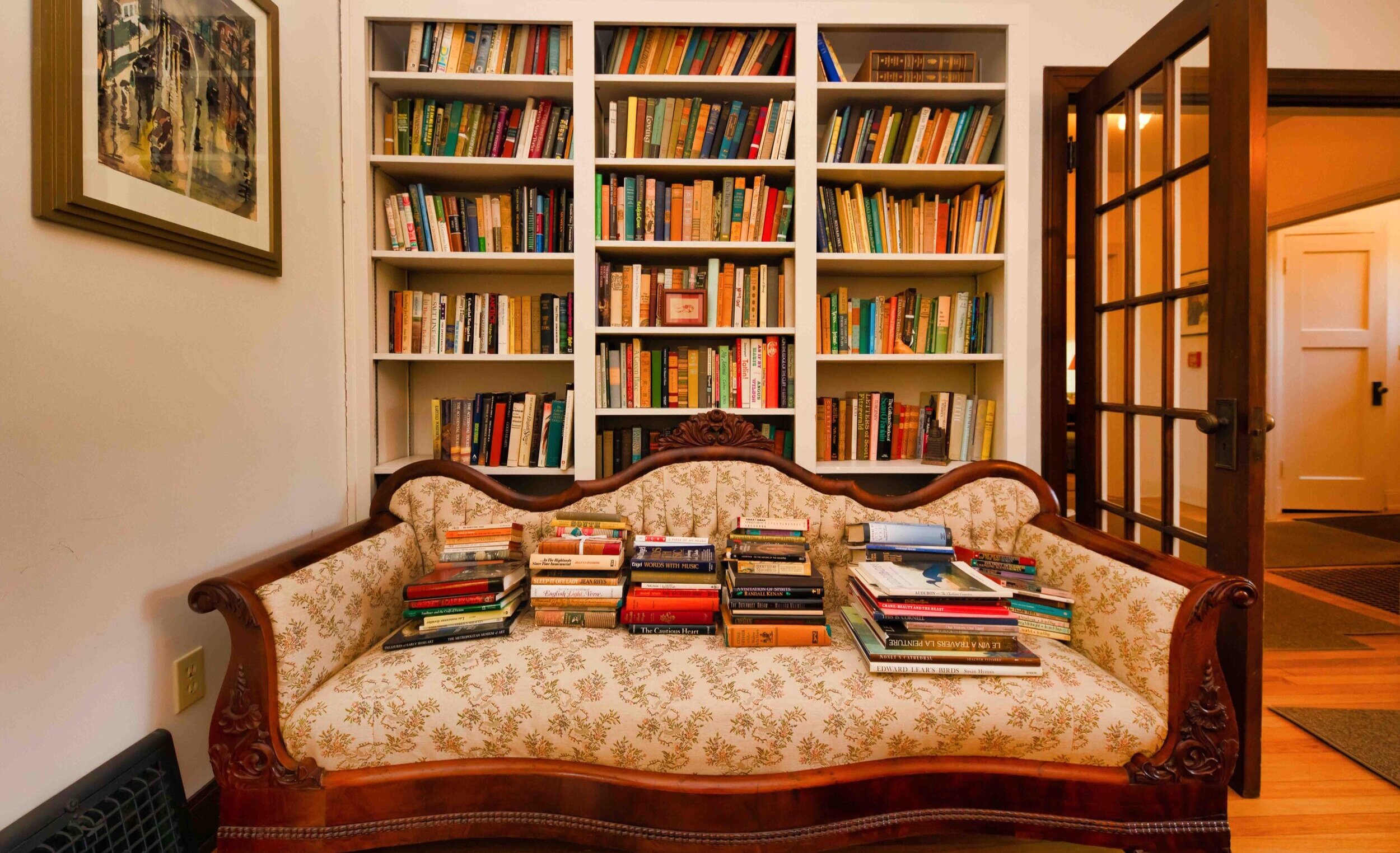

This is obviously a writer’s house, with books in every room. I looked for books turned upside down, left where Welty stopped reading. I didn’t find any, but upstairs is her collection of well-worn mysteries, even dime store paperbacks with garish noir covers, that she loved. For years, she and the Canadian-American mystery writer Ross MacDonald carried on a correspondence.

In Welty’s large living room, she left a drinks bar with a full shelf of bourbon and whiskey bottles. She enjoyed entertaining and, having worked briefly as a journalist, liked hanging out with reporters. Certainly the famous photographs she took for the Works Progress Administration of daily life in rural Mississippi in the 1930s can be considered photojournalism.

Every room in Welty's house features piles of books. Michael Pickard, professor of English at Millsaps, points out, "Surrounded by books, she lived without a washing machine, a dishwasher, a microwave, or central air conditioning." Photo by Tom Beck courtesy of MDAH

Dixie, Curtis Wilkie’s 2001 collection of essays on his life and career covering the South, begins with a description of a Belhaven dinner party whose guests included Willie Morris and Welty, then almost 85. Wilkie recalls that when he offered to refill Welty’s whiskey glass, she asked him to “make the next one a bit stronger.”

This photo of a photo from One Writer’s Beginnings shows Welty at work on her bed in the 1940s. Simon and Schuster, Scribner Books

Wilkie asked “a question I’m sure Miss Welty had answered many times: How was she able to write the short story ‘Where Is The Voice Coming From?’ so quickly, and with such prescience?” This story is “a cold-blooded, first-person account of a racial murder” that The New Yorker had published shortly after Medgar Evers was murdered in June 1963. In summer 2019, during Black Lives Matter protests around the country, The New Yorker republished Welty’s story.

To mark the 50th anniversary of Evers’ death in 2003, reporter Jerry Mitchell, with help from Welty scholar and friend Suzanne Marrs, persuaded the Jackson Clarion Ledger to publish the original, unedited version, which named Jackson and Evers, and included many local spots with names long familiar to Jackson residents. The draft shows that Welty considered calling the story “It Ain’t Even July Yet,” a title which would have foreshadowed the murder of the four little girls in the bombing of a Birmingham church on September 15, 1963.

When Welty finished her story, Evers’ assassin, Byron De La Beckwith, hadn’t been arrested, so The New Yorker changed names for fear of libel. Yet, Wilkie writes, “The narrator’s hate resembled Beckwith’s. The physical description a reader could infer matched Beckwith. Even the monologue sounded like Beckwith.”

To Wilkie, Welty “dismissed the notion that she had been remarkably foresighted.” At the dinner party -- as she wrote in her memoir, One Writer’s Beginnings -- Welty explained that she had written the story in a heated fury, hours after learning what had happened to Evers. “We all knew who did it because we all knew Beckwiths,” she told Wilkie. “It wasn’t necessary to know that man, Beckwith.”

Welty used her typewriter on her bed as well as on her desk on the opposite side of her bedroom. Photo by Tom Beck courtesy of MDAH

Welty told Jerry Mitchell that the story was the only one she’d ever written in anger. In One Writer’s Beginnings, she writes, “I don’t believe that my anger showed me anything about human character that my sympathy and rapport never had.” Readers may feel differently.

Wilkie, Mitchell and other authors are following Welty’s example of making Mississippi a wonderful place to write. Marrs and Michael Pickard, professor of English at Jackson’s Millsaps College, where Welty sometimes taught, are at work on a book about the connection between Welty’s house and gardens and her work. Pickard points out that Welty called her “most significant choice” the one “to do my writing in a familiar world.” If you’re in Jackson, be sure to visit Welty’s house and gardens, which bloom all year, and allow them to inspire you.

Ann Marie Cunningham is a Columbia University Lipman Fellow for 2020 who will be working with the Mississippi Center for investigative Reporting. She is a veteran journalist/producer and author of a best-seller. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Technology Review, The Nation and The New Republic. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.