The journalist who concealed the lynchers in the Emmett Till case got away with his crime

Jill Collen Jefferson

By Jill Collen Jefferson

Books, documentaries and an FBI investigation detail the abduction, torture and murder of Emmett Till 66 years ago, but one person who should have been charged in the case has never been identified.

On the night of Emmett Till’s abduction, torture, and murder, men and a woman took him from his Uncle Moses Wright’s home. At least two Black men kept him from jumping off the back of the 1955 green and white Chevy pickup that transported him. At least four white men beat, pistol whipped, and shot him point blank in the head, killing him. They then tied a cotton gin fan to his neck with barbed wire and threw his naked body into a muddy bayou that spilled into the Tallahatchie River.

Most of us believe a different narrative—a lie—created by the late journalist William Bradford Huie. In 1955, over a year after Brown had overturned separate but equal and just two months before Rosa Parks would change civil rights forever on a Montgomery bus, Huie sat in the law office of J.J. Breland and John Whitten, two of the five defense counsel for two of Till’s killers—J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant. The two had already been tried and acquitted of Till’s murder. Now, Huie and their attorneys negotiated a deal where the killers would tell him details of their crimes. It would be the first time any of them had done so publicly, and what a sensation it would be. But there was a problem.

As Dave Tell points out in his book, Remembering Emmett Till, Huie needed releases from the murderers to indemnify Look magazine from litigation. But he couldn’t get four. He could only get two. So, he made his story fit his resources. He shrank the kidnapping and murder party to two and moved the murder scene as a consequence. So, instead of telling readers the truth—that Till’s lynchers killed him in a barn on a plantation run by Leslie Milam, a member of the killing party whom Huie concealed—he claimed J.W. Milam and Bryant beat Till near J.W. Milam’s home and shot him to death on the Tallahatchie River’s bank.

Like others, I first noticed Huie’s deception when I compared letters he’d written to different people over the course of 11 days. In a letter to NAACP leader Roy Wilkins on Oct. 12, 1955, he wrote, “Two other men are involved: there were four in the torture-and-murder party. And if I name them I must have their releases—or no publisher will touch it. I know who these men are: they are important to the story; but I have to pay them because of their ‘risks.’” Here, he admits that there were four in the killing party. He says so again in an Oct. 17 letter to Look magazine editor Daniel Mich. “My effort will begin with a secret deal among four ‘Southern Gentlemen:’ me, Breland, Whitten, and one of the four murderers.”

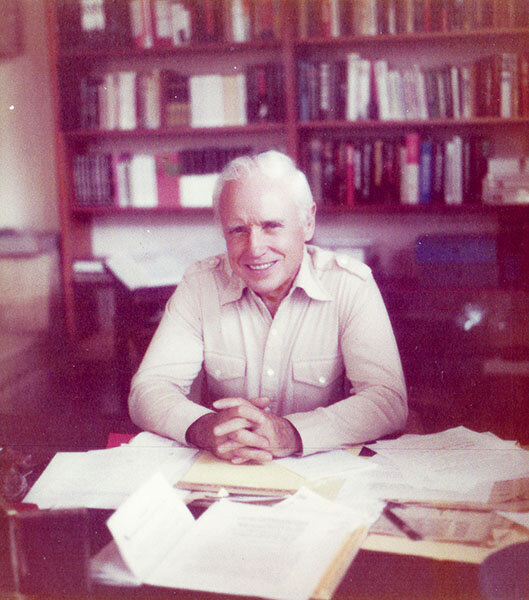

William Bradford Huie Encyclopedia of Alabama

Five days later, however, he does an about face, now claiming that there were only two murderers, and conveniently, the two were the same ones who’d signed releases. “Of this I am now certain,” he declared. “[T]here were not, after all, four men involved in the abduction-and-murder: there were only two. So when we have these releases from Bryant and Milam and the woman, we are completely safe.”

This single passage where Huie changes his story and puts the fabrication in writing evidences that he concocted and subsequently disseminated a fiction where he concealed the identities of other killers—Leslie Milam, Elmer Kimbrell, Melvin Campbell, Hubert Clark—so that he wouldn’t have to obtain their releases. With that single, solitary line, he opened the door to what could have been a charge of accessory after the fact to kidnapping and to murder.

He also conceals their accomplices by omitting and later trying to discredit the testimony of sharecropper Willie Reed, who saw Black men holding Till in the back of a pickup, men later identified as Levi “Too Tight” Collins, Henry Lee Loggins and Johnny B. Washington.

In the 19th century and at least the first half of the 20th, there were very few decisions in Mississippi that interpreted the state’s accessory statute. The first case dealing with the question is Harrel v. State, 39 Miss. 702 (1861), where the Mississippi Supreme Court held that an accessory after the fact is one who gives aid and assistance after a felony is fully completed.

Huie met this element of the offense when he concealed the identities of Till’s other murderers, first in his Oct. 23 letter to Dan Mich, where he lied about Till being killed by two men instead of four, and again in his published article where he disseminated that lie. Plus, Till’s kidnapping and murder — both felonies — had been completed by the time he fabricated his story.

Emmett Till National Museum of African-American History and Culture

In a 1937 case, Crosby v. State, where appellant Crosby was charged with being an accessory after the fact to murder, the court found that “[i]n order to convict [Crosby], the State must prove (1) that Williams feloniously killed Lizzie Marsh, and (2) thereafter the appellant, with knowledge thereof, committed specific acts with intent thereby to enable Williams to escape, or to avoid arrest, trial, conviction, or punishment.” Crosby v. State, 179 Miss. 149, 175 So. 180 (1937).

If we apply the court’s ruling to Huie’s acts, we see that during Till’s trial, the state proved that Milam and Bryant had feloniously killed Till. Even counsel for the defendants themselves admitted the half-brothers had killed him. Huie knew they’d killed him. That’s the very reason why he wanted to interview them, so he satisfies the “knowledge” requirement. Then, he committed the specific act of making up a lie, which concealed key details of their crime, including other killers who had not yet been charged. It’s clear that part of his intent was to help them escape prosecution because:

1) He’s deliberate in his telling of events, making sure not to implicate anyone. He says as much in his Oct. 12 letter to Wilkins. Explaining how he would approach his agreement with Milam and Bryant’s attorneys, he wrote:

“I would have to give my personal work to Breland & Whitten that I would not claim that Milam and Bryant had ‘confessed;’ that I would write the facts of the crime without ever stating that either of the defendants ‘told’ me anything.”

2) As mentioned above, he only obtains releases for two of the killers and massages the story’s facts to make them fit his resources after he’d already admitted to knowing there were at least four killers in his letter to Wilkins and in his Oct. 17 letter to Mich. The natural inference from these facts is Huie’s intent was to enable the others involved to escape prosecution. He could not have made the decisions he made without forming that intent.

3) Had that not been his intent, he would have opened himself and the magazine to suit. Had Huie named the other killers, they could have sued him and Look magazine for libel because they had not released their stories to Huie, confessed or been tried.

Moreover, the Mississippi Supreme Court had found as early as 1950 that “even an acquittal of a supposed principal” in a crime doesn’t bar an accessory from being prosecuted “where the fact of crime is clearly established.” Till’s murder had been clearly established before and during Milam and Bryant’s trial. So, even though they were acquitted and no one else had been charged in his death, Huie still could have been charged as an accessory.

Emmett Till poses with his mother. National Museum of African-American History and Culture

It’s notable that of all the care Huie took to ensure he was safe from civil litigation he overlooked such a blaring criminal violation. More than likely though, he simply ignored it because he knew he wouldn’t be charged. The state of Mississippi had just acquitted two of Till’s killers and were every day failing to charge others. It would embarrass the state to charge a journalist when they wouldn’t even charge the killers. Huie likely considered this fact and assumed he was safe. So, seemingly without remorse, he devised one of the most infamous lies of civil rights history. And its effects haunt Mississippi and the nation still.

When I was growing up in Mississippi decades after Emmett’s death, older Blacks would become quiet when I asked them about Till. I remember asking my hair dresser while I balanced on a rickety chair in her kitchen one afternoon. We’d been chatting for almost an hour while her hot comb sizzled through my hair. As I sat there, holding down one ear so she wouldn’t burn it, my question stopped the conversation and the comb at a dead halt. I turned around and looked up at her. From her eyes and the look on her face, it was fear that shut her up — not just fear of harm but fear from such horrific violence being perpetrated by only two people. Huie’s lie elevated Black fear in Mississippi just as it catalyzed Blacks in other places like Montgomery, Alabama. According to him, just two white people, outnumbered by your own family, could take you from your bed, torture you to the point where you’re unrecognizable and get away with it. It didn’t take a pack. It could happen more easily than that. It could happen to you.

Due in part to Huie’s story, the other killers and kidnappers were never charged, and Carolyn Bryant Donham, Roy Bryant’s wife who accused Till of accosting her, remains free. So, in many ways, Huie fulfilled the powerful myth he created of Bryant and Milam: One white man, outnumbered by witnesses, court records,and the truth, concealed the most infamous lynchers in this nation’s history. And he should have been charged for it.

Jill Collen Jefferson is a civil rights and international human rights attorney who grew up in the racism and de facto segregation of rural Mississippi. Prior to her legal career, she researched civil rights cold cases, was one of four speechwriters on President Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign, and served in various roles on Capitol Hill, The White House, national and state political campaigns, think-tanks and advocacy nonprofits. She is the founder of Julian, a civil rights and international human rights organization, providing legal services to victims and survivors of discrimination. She earned her bachelor’s degree with distinction in English and History along with a minor in French at the University of Virginia and her J.D. from Harvard Law School. She hails from a farm in southeastern Mississippi.

The Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting is a nonprofit news organization that seeks to inform, educate and empower Mississippians in their communities through the use of investigative journalism.

Sign up for our newsletter.