Mississippi Activist Fannie Lou Hamer’s Legacy: A New Film Elevates Her Voice

I first heard Sweet Honey in the Rock’s rousing song, Fannie Lou Hamer, on a car radio a summer day in 1994 when Nelson Mandela addressed the United Nations General Assembly. The song and the moment were very powerful, but not as strong as Hamer’s own voice, raised in song or to protest conditions for Black Mississippians in the 1960s and 1970s.

Monica Land, great-niece of the Mississippi activist, grew up in Chicago but visited Hamer every summer at her home in the Delta’s Sunflower County. Land always saw her great-aunt lying on a couch; she died in 1977 at age 59, when Land was 9. Like too many people in the Delta, Hamer had diabetes – along with breast cancer and permanent kidney damage from beatings she received when she was arrested in 1963 in Winona. But Land remembers Hamer as entirely welcoming, hospitable, loving: “She loved to joke and laugh, cook and eat. She was an extremely hard worker and strong-willed person.”

Land, now a prize-winning veteran journalist in Mississippi, worked for 15 years to executive produce a beautiful new documentary, Fannie Lou Hamer’s America, about her great-aunt. The documentary’s most striking part is it tells Hamer’s life story in her own voice – her singing, her interviews filmed during her lifetime – with no other narrator. On Tuesday, Feb. 22, PBS stations across the U.S. will broadcast Fannie Lou Hamer’s America.

Fannie Lou Hamer of Ruleville, Miss., speaks to Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party sympathizers outside the Capitol in Washington, Sept. 17, 1965, after the House of Representatives rejected a challenger to the 1964 election of five Mississippi representatives. Hamer and two other African American women were seated on the floor of the House while the challenge was being considered. “We'll come back year after year until we are allowed our rights as citizens,” Hamer said. The challengers claimed that African American were excluded from the election process in Mississippi. AP Photo/William J. Smith

In 1964, then-NBC newscaster David Brinkley summarized Hamer’s very direct style: “She has a gift for earthy and vivid phrases, stating her views without formality, cant or hypocrisy.” When she appeared on Irving “Kup” Kupcinet’s television talk show in Chicago, the host introduced her as “the sparkplug of the Mississippi Freedom [Democratic] Party” – one of Land’s favorite descriptions of her great-aunt. One of Hamer’s memorable phrases was “Mississippi appendectomy” – her description of being sterilized without her knowledge or consent, as more than a million Black and Latina women were from the 1920s until at least the 1980s.

Hamer didn’t look, sound or act the way male leaders of the civil rights movement thought a leader should. Because she lived in the most dire poverty all her life, she was not well-educated. She left school after sixth grade to help support her sharecropping family by picking cotton. Other civil rights leaders disdained her diction and grammar. A small, heavy-set woman who limped thanks to a broken leg weakened by a childhood bout of polio, she had to borrow dresses and handbags for public appearances.

But these apparent detriments made Hamer a successful organizer in the Delta. Along with her mentor, Ella Baker, cofounder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1960, Hamer believed grassroots organizing was the key to success. She knew local rural people in Mississippi who never could wear new clothes, would respond best to someone who looked and sounded like their mother or aunt, someone who knew her way around their communities.

Inside Convention hall: Fannie Lou Hamer and Bob Moses assess the Mississippi seating situation at the National Democratic Party Convention in Atlantic City, N.J., on Aug. 10, 1964. George Ballis /Take Stock

In Joy Davenport, Land found a director/editor who strongly agreed that the documentary should tell Hamer’s story in her own voice. They described their position during a panel discussion with actress Aunjanue Ellis, who grew up in south Mississippi and is developing a feature film about Hamer plus an outreach project, and historian Keisha N. Blain, Ph.D., author of Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message to America. Davenport explained the choice of using only Hamer’s voice for the film: “I’m a White woman. In the feminist movement, White women have had a bad reputation of speaking for Black women.”

After raising funds, the filmmaking team began serious field work in 2016. They had a difficult time finding stock footage of Hamer because films of her speeches often were labeled only as “Black woman speaking.”

Hamer couldn’t have children of her own, so she and her husband adopted four local girls, one of whom, Jacqueline, known as Cookie, survives today. Like her mentor Baker, Hamer loved working with young people, encouraging them to develop their own voices rather than following the agenda of the older men with suits, ties and degrees at the national Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

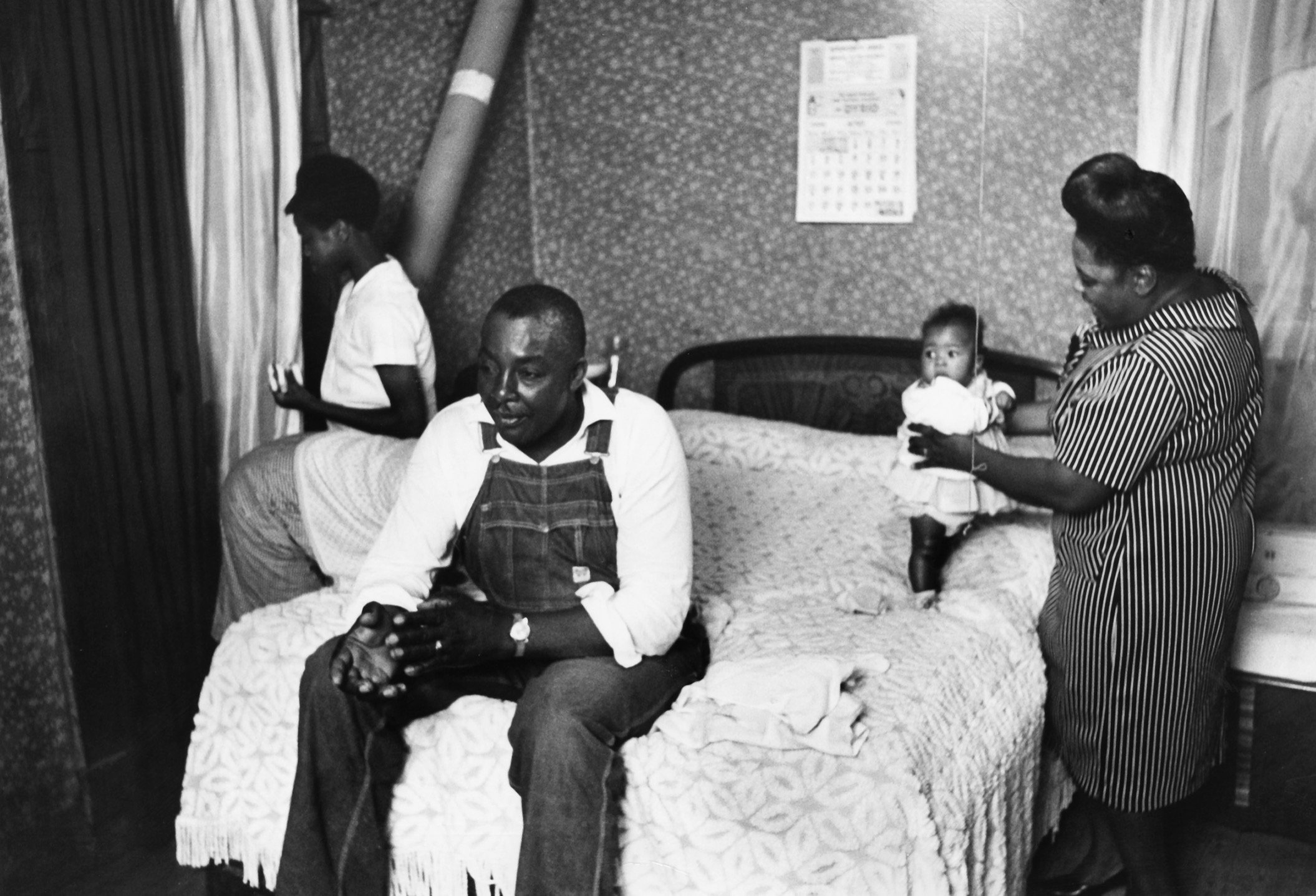

Foster mother to two children, Fannie Lou Hammer is photographed playing with 7-month-old Lenora Aretha. National Museum of African American History G. Marshall Wilson/EBONY Collection

Fannie Lou Hamer’s America is the centerpiece of Land’s larger project to educate new generations about her great-aunt’s work. “People either know all about her,” Land said, “or they’ve never heard of her” – which she has found is particularly true of younger people. During the panel, Blain and Ellis pointed out that they never heard about Hamer in a classroom until after high school. At present, Blain said, a proposed Mississippi history curriculum would mean that students would not hear about activists like Medgar Evers, James Meredith or Fannie Lou Hamer until high school. So Land is collecting a K-12 curriculum and other educational material on a website, www.fannylouhamersamerica.com.

Land is continuing Hamer’s work with young people by founding the Sunflower County Film Academy. Every summer, film professionals, including Black Hollywood producers, Davenport and Pablo Correa, videographer for Fannie Lou Hamer’s America, teach young people from the Delta to make their own films. “It wasn’t that long ago that I learned how to use a camera,” Davenport said, “or how to put pictures and sound together [in the editing suite]. I remember how powerful that makes you feel.”

In today’s America, as in Hamer’s, many are poor and hungry, and many are restricted from voting. The point of the Film Academy is to help young people document their own families’ histories, and to discover that their own voices on today’s issues could be as important as Hamer’s was.

Fannie Lou Hamer’s America will have its world premiere as a special presentation from PBS and WORLD Channel on Tuesday at 8 p.m. CT, 9 p.m. ET. Viewers will have a second chance to see the film on Thursday, Feb. 24, at 7 p.m. CT, 8 p.m. ET, 9 p.m. Pacific on WORLD Channel stations nationwide.

The film is airing as part of the documentary series America ReFramed, presented by WORLD Channel and American Documentary Inc., and its premiere marks the start of America ReFramed’s 10th season on the air.

In addition to airings on PBS and WORLD Channel, Fannie Lou Hamer’s America will be available for streaming, as of Feb. 22, on worldchannel.org, the WORLD YouTube Channel and on all station-branded PBS platforms including PBS.org and the PBS Video app.

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegates challenge Mississippi Democrats National Democratic Party Convention in Atlantic City, N.J., on Aug. 10, 1964. Fannie Lou Hamer, center, sings during a MFDP rally on the boardwalk, along with, from left, Emory Harris, Stokely Carmichael (straw hat), Sam Block, Eleanor Holmes Norton and Ella Baker. George Ballis/Take Stock

Ann Marie Cunningham is MCIR's Reporter in Residence. She holds a 2021 grant from the Domestic Violence Impact Reporting Fund at the Center for Health Journalism at the Annenberg School of Journalism at the University of Southern California. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.

.jpg)

.jpg)