Two New Documentaries Made By Women: A Lot to Learn About Racism in America

If you don’t know much about Black history, or not as much as you’d like, all you have to do is watch two documentaries in February, Black History Month. Women with distinguished civil rights forebears made both these documentaries, and both films use innovative techniques.

Documentarians, Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler, based in New York City, are the daughters of the late William Kunstler, the criminal defense and civil rights lawyer best known for defending the Chicago Seven from 1969 to 1970. In the early 1960s, Kunstler came to Mississippi to defend the Freedom Riders. In fact, a third Kunstler daughter, Karin, who was attending Tougaloo College near Jackson, was among them. In 1970, William Kunstler returned to Mississippi for a case that went all the way to the Supreme Court, an attempt to prevent Jackson from closing its swimming pools to avoid desegregating them.

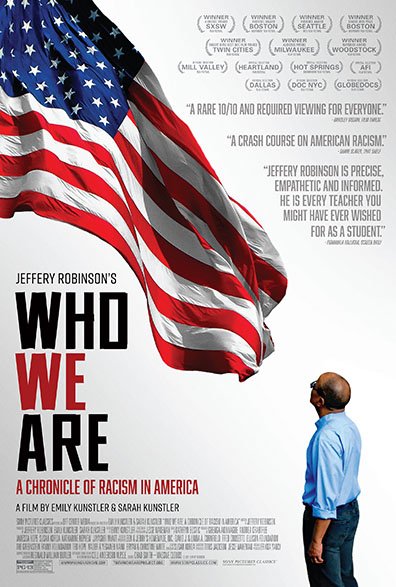

New York-based documentarians Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler, daughters of the late civil rights attorney William Kuntsler, filmed criminal defense lawyer Jeffrey Robinson in locations across the country as he discussed the role of white supremacy in America for the film Who We Are. Photos courtesy of Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler

Like her father, Sarah Kunstler is a criminal defense lawyer, as well as a filmmaker. Three years ago, she attended a continuing education course in a New York City courthouse’s bare bones conference room. Jeffrey Robinson, a criminal defense lawyer for the ACLU, presented the course. For the past seven years, Robinson had been traveling around the country giving his own lecture, presenting the case for the racism underlying America’s history. It was only a PowerPoint presentation, but Sarah was struck by Robinson’s graceful and eloquent approach, the power of his argument, and the effect of seeing him present his case in others’ company.

Sarah immediately told her sister Emily that they had to turn Robinson’s work into a film. They filmed Robinson in New York on stage at The Town Hall, talking to a live audience. The sisters worked as field producers, filming Robinson talking to locals in Memphis, where he grew up, and in other locations for the documentary Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America.

“We wanted to make sure every scene was a conversation,” Sarah said. “No talking heads.”

At the beginning of the film, Robinson says, “Don’t believe a word I say” about America’s roots in white supremacy. His point is you don’t have to take his word for it. Today the original documents are available on the Internet to anyone who wants to read them. You can see for yourself what the Founding Fathers wrote to each other about keeping slavery, and what the states that seceded from the Union wrote about why they did so.

At a Q&A after the film opened in New York City, Robinson was asked what surprised him the most. “The Founding Fathers’ correspondence, and how open they were about preserving slavery,” he said. “As criminal defense lawyers, Emily and I have met wonderful people who did terrible things. You could count people like James Madison among them.

“I also was struck by the bluntness of the states’ articles of succession. They were clear that they were leaving the union to keep slavery because it protected their economic interests.”

Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America opens this week in 300 AMC theaters nationwide.

Before the Civil War, Robinson points out in Who We Are, Mississippi was the most prosperous state in the union, with many millionaires. He quotes Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, for whom many Mississippi streets and a county are named, as saying, “If we aren’t fighting for slavery, what are we fighting for?”

For me, the most shocking part of Who We Are was the singing by a mixed-race choir of the racist third verse of The Star-Spangled Banner, written by Francis Scott Key, who like many slave-owners feared the British promised refuge to any enslaved Black people who escaped their enslavers would lead to a large-scale revolt:

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave

By spring 2021, the Kunstler sisters were struggling to edit and complete their documentary at their family’s house in the Catskills, despite the pandemic and their four children. “We lost three babysitters,” Emily said.

Meanwhile, Robinson left the ACLU to become executive director of The Who We Are Project, to “provide an objectively true account [of American history] that exposes the role of white supremacy and anti-Black racism” that continues today. The project’s goal is to work with partners to distribute the Kunstlers’ new documentary, Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America, as well as supplementary educational materials.

This week, Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America, opens in 300 AMC theaters all over the country. Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler hope families will see it and discuss it together.

In Who We Are, Robinson does mention the heroism of some Black women activists, including Emmett Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, and the three female founders who set up Black Lives Matter so the new civil rights movement could flourish without one single leader who could be assassinated, like Medgar Evers, Malcolm X or Martin Luther King Jr. But there is one important Black woman leader who is not in Who We Are.

That is why, besides Who We Are, you also must see Monica Land’s Fannie Lou Hamer’s America.

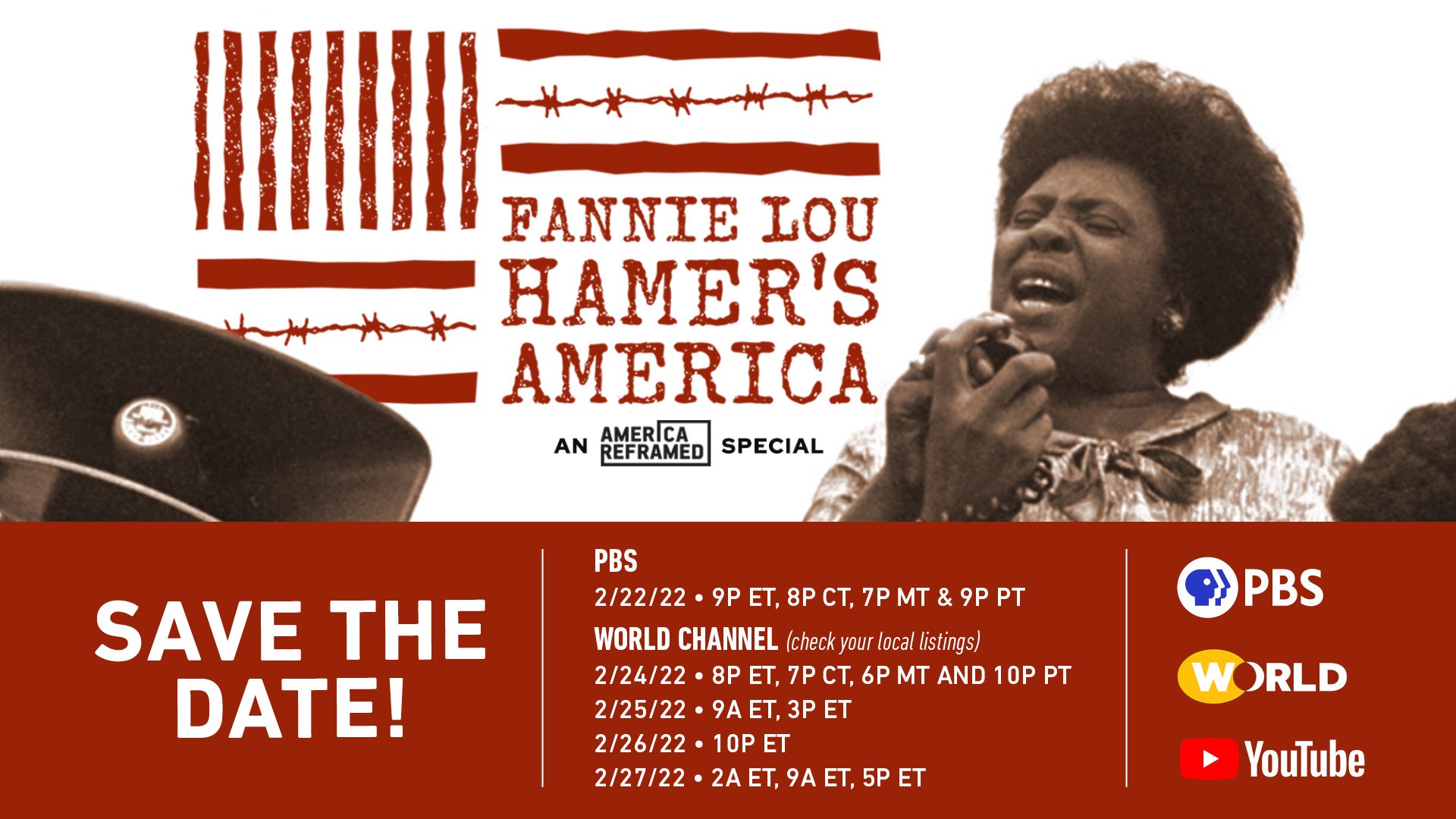

Monica Land, a veteran investigative reporter, has produced a documentary about her great aunt, civil rights icon Fannie Lou Hamer, that will air Feb. 22 on PBS. Photo courtesy of Monica Land

Land, a veteran investigative reporter living in Mississippi, is a great-niece of the redoubtable Fanny Lou Hamer. Like the Kunstler sisters, Land decided to avoid talking heads. Fannie Lou Hamer’s America uses only Hamer’s own words. Along with other members of the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Hamer demanded to replace the all-White Mississippi delegation. Her speech to the credentials committee —”I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired”--was carried on national television, terrifying President Lyndon B. Johnson that he would lose the support of the Deep South and along with it, his party’s nomination for a second term.

Well-educated civil rights leaders often did not want to appear on stage with Hamer: She was a sharecropper who had left grade school to support her family, and her diction wasn’t what others with doctorates thought it should be. But she was extremely eloquent and a talented singer.

Fannie Lou Hamer’s America, directed by Joy Davenport, is narrated entirely by Hamer, in her own words. What she had to say about hunger, endemic in the Mississippi Delta where she grew up, is especially striking.

Land has spent the last several years developing a website devoted to Hamer, educational materials, including a curriculum, and the documentary. On Feb. 22, Fannie Lou Hamer's America will be broadcast nationally on public television at 8 p.m. central time, including Mississippi Public Broadcasting, to open the 10th season of PBS’s Emmy-award winning documentary series, America Reframed. Meanwhile, enjoy a three-minute clip from the film and Hamer’s powerful voice on Land’s website.

On February 22, Fannie Lou Hamer's America will be broadcast nationally on public television.

Ann Marie Cunningham is MCIR's Reporter in Residence. She holds a 2021 grant from the Domestic Violence Impact Reporting Fund at the Center for Health Journalism at the Annenberg School of Journalism at the University of Southern California. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.