Moses Way Down Mississippi-land: A Tribute in Jackson to an Advocate for Civil Rights and Math Education

Some historians of the civil rights movement think Bob Moses, who died in July 2021, was as influential as Martin Luther King Jr., if not more so. A brilliant organizer and tactician, Moses was a tall, quiet man -- reliably referred to as a “gentle giant.” He always sought consensus, always spoke softly and calmly, and preferred working behind the scenes to standing on a stage before a microphone. Unlike Black preachers, Moses had a mysterious air because he was always thinking.

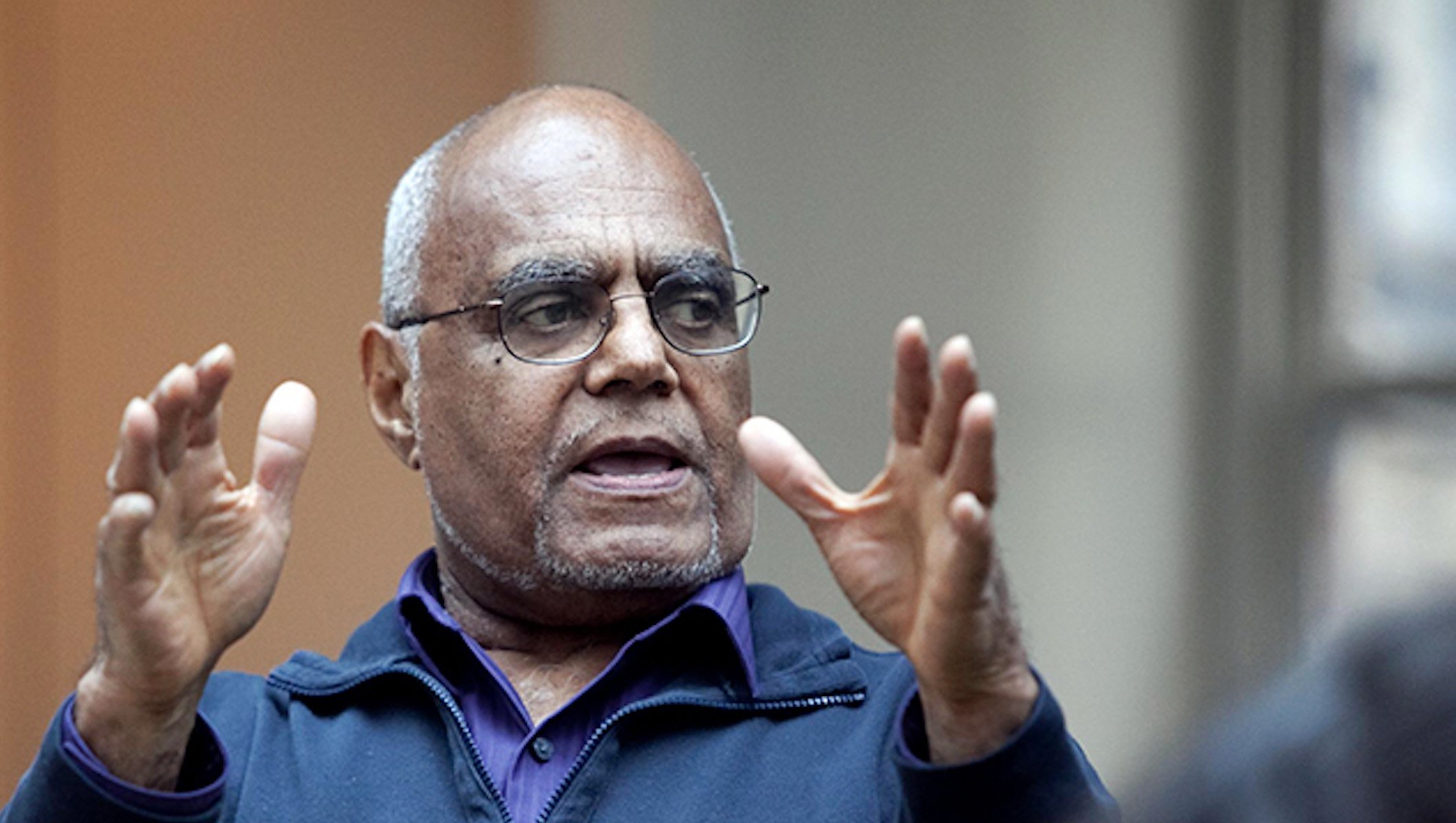

Activist and Algebra Project founder Bob Moses, who died in July 2021, is pictured here in this Polycentric University News Center photo. He spoke at CalPoly Pomona on Feb. 26, 2020, about the legacy and lineage of civil rights and the importance of educational equality and math literacy.

On Nov. 11, 2021, Tougaloo College, just outside Jackson, honored this veteran of civil rights organizing in Mississippi with a memorial in its chapel. The lofty chapel, with lamps that originally were gaslights, looks exactly as it did when Medgar Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer and King himself spoke there in the early 1960s. The gathering included audience members and speakers in wheelchairs and on walkers, poignant reminders of how few veterans who tried to “turn civil wrongs into civil rights,” as one speaker said, are still alive today.

Tougaloo is the only HBCU that is a former plantation, according to faculty member Daphne Chamberlain, Ph.D., civil rights historian. Tougaloo’s first White alumna, Joan Trumphauer, recalls in An Ordinary Hero, her son’s documentary portrait, that the 500-acre campus was “the only place in Mississippi where you could feel safe” if you were a civil rights worker in the 1960s. She remembers that Bob Moses worried when he was organizing 1964’s Freedom Summer. He was not afraid to die. But in good conscience, could he urge students from Northern states to come to Mississippi and risk their lives registering Blacks to vote?

“We knew someone would be killed,” Trumphauer recalls. Sure enough, in June 1964, James Chaney, Andy Goodman and Michael Schwerner were: The Ku Klux Klan wanted to halt Freedom Summer. “Because we weren’t killed,” Trumphauer says, “our friends were.”

Outside the historic chapel, Chamberlain pointed out Trumphauer’s dorm, where she lived across the hall from author and civil rights activist Anne Moody. In the building named for alumnus and U.S. Rep. Benny Thompson, there is a wall-sized photo of the two young women and other Tougaloo students and staff being mobbed at the violent 1963 sit-in at Woolworth’s counter in Jackson. At the pond near the campus entrance, King and other notables stopped during James Meredith’s 1966 March Against Fear from Memphis to Jackson.

In 1960, Bob Moses came to Jackson from his native New York City to work for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and later the Council of Federated Organizations, an alliance of civil rights groups that he and Medgar Evers founded to organize Freedom Summer and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. In Jackson, Chamberlain said at his memorial, you can visit his old COFO office, which is now a museum.

As a New Yorker, I feel proud that Moses grew up in Harlem and went to Stuyvesant, the very best of the city’s elite high schools. As a former French major, I feel proud that he studied French at Hamilton College and went on to earn a master’s in philosophy at Harvard. Studying Jean-Paul Sartre and other French existentialist philosophers gave him the courage to go to Mississippi in 1960. Today, I have trouble taking in what a dangerous decision that was: In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Mississippi had the most lynchings of any state. Everyone knew what had happened in 1955 to 14-year old Emmett Till in Mississippi.

At Moses’ memorial, the small stage held a single candle over a large photo of him late in life, with bulky shoulders and a broad smile. I prefer the photo behind that image on the program cover: skinny, serious young Moses of the early 1960s, thick black eyebrows level over his heavy-framed glasses. Coming from the nation’s fashion capital, Moses was aware of the messages clothing can send, so in Mississippi, he began wearing T-shirts and overalls like the sharecroppers he wanted to convince to register to vote.

In the late 1970s, after eight years living in Africa with his family, Moses went back to Cambridge, Massachusetts, for doctoral studies at Harvard. He was frustrated that his daughter Maisha’s eighth grade did not offer algebra. At the Tougaloo memorial, Maisha, the eldest of Moses’ four children, recalled her father sitting silent in his favorite chair for an entire day and simply staring into space. Once he finally stood, Maisha said, “he never stopped moving. Something had shifted in him; I could feel it. And I think that is when the Algebra Project was born.”

Moses had become convinced that access to advanced mathematics, the language of the sciences, meant for Blacks today what the right to vote had meant in the 1960s. It was their key to access, this time to economic success in the 21st century. He personally established his nonprofit Algebra Project in Jackson to introduce students of color and low income to advanced mathematics starting in middle school. With its spin-off, the Young People’s Project, the Algebra Project now reaches hundreds of thousands of students across the country.

At the memorial, Omo Moses, Moses’ son, said his father never lost his love of Mississippi. He described driving with Bob across the Delta along Mississippi Highway 24 on cruise control. (“24! That was a dangerous road,” said lawyer Isaac K. Byrd, another civil rights veteran, recalling the dense woods along it. “I did not go on that highway without my .38!”)

“You couldn’t tell him [that was dangerous],” Omo Moses recalled. “He was in his place.”

MADDRAMA Performance Troupe, a student theater group from Jackson State University, illustrated Bob Moses’ belief in the power of young people. Not only are most of the members from places like Chicago and Los Angeles, but several are studying science. Moses’ work is not done, they told memorial attendees: “The murder rate is higher than the graduation rate. Girls are carrying babies, not school books.”

To learn more about Moses and his projects, read his book, Radical Equations, written with Charles E. Cobb.

Ann Marie Cunningham is MCIR's Reporter in Residence. She holds a 2021 grant from the Domestic Violence Impact Reporting Fund at the Center for Health Journalism at the Annenberg School of Journalism at the University of Southern California. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.