Carolyn Bryant lied about Emmett Till. Did author Tim Tyson lie, too?

By Jerry Mitchell

Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting

The Justice Department has closed the books on the lynching of Emmett Till, whose face — young and unblemished, then swollen and monstrous — has come to symbolize the unpunished killings of Black Americans.

Whatever hope there was for justice was dashed this week when the department pinned the blame on its inability to confirm a book’s explosive 2017 claim that the White woman at the center of the case recanted her story about Till’s actions that fateful day in Money, Mississippi.

The decision hardly surprised me. What author Tim Tyson has shared with me has never added up.

When I first met him in 2008, he told me he was going to talk with Carolyn Bryant Donham, the woman at the center of the Till case. I congratulated him on landing such a coveted interview.

The next time we met for lunch at Hal & Mal’s in Jackson, Mississippi, he shared that he had finished talking with her.

I asked if she had changed the story she had testified to in 1955 when she claimed that Till had attacked her. He said no, she had stuck to her story.

“You know she lied, don’t you?” I asked.

He seemed surprised and said he didn’t know that. Afterward, I mailed him a copy of the statement she had made to a lawyer for her husband, Roy, one of Till’s abductors and killers, shortly after his arrest.

In that Sept. 2, 1955, statement, she painted a picture of a 14-year-old boy from Chicago grabbing her hand, asking for a date and saying, “What’s the matter, baby, can’t you take it?” before walking out the door.

Seventeen days later, her husband’s attorney, Sidney Carlton, announced to reporters that Till had all but raped her — a lie she repeated from the witness stand. In this version, Till was the predator, attacking her, grabbing her by the waist, refusing to let her go and telling her that she didn’t need to be afraid because he had “f---ed” white women before.

Till’s cousins, Wheeler Parker and Simeon Wright, told me they never saw Till say or do anything to Donham — then Carolyn Bryant — inside the store on that evening of Aug. 24, 1955.

Parker said when they emerged from the store, Till wolf-whistled at her. When someone said she had a gun, Parker said the cousins jumped into a car and sped away.

Four nights later, it was “as dark as a thousand midnights” when he said he awoke to the sound of men with guns. He shook with fear, he recalled. “It was pure hell. It was pure terror.”

The men warned Wright’s father, Moses, that if he talked, he would be killed.

But Moses Wright did talk. He told authorities what these men had done, and Till’s body was found floating in the Tallahatchie River three days later.

At the 1955 trial, Wright identified Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam as the men who abducted Till, but the all-white, all-male jury acquitted them.

Months later, Bryant and Milam confessed to Look magazine they had killed Till, and the journalist who wrote the article helped conceal the names of the other killers.

In the decades that followed, the case grew cold.

***

I began investigating unpunished killings from the Civil Rights Era in 1989. A year later, a Mississippi grand jury indicted Byron De La Beckwith for the 1963 murder of Medgar Evers.

Months later, I interviewed Till’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley. She told me that she left her son’s casket open because “I wanted the world to see what I had seen.”

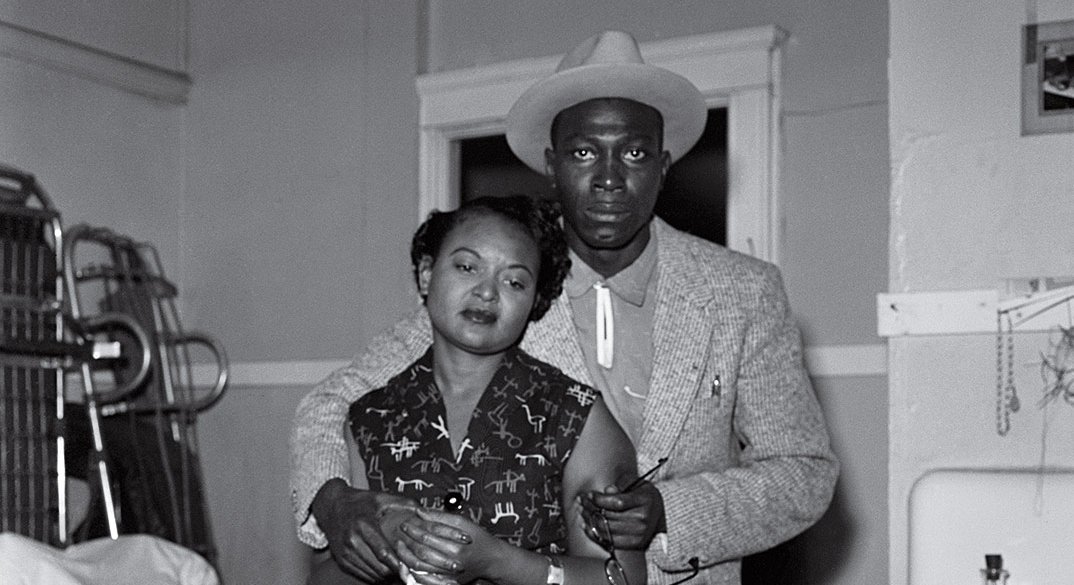

Mamie Till looks at the brutalized body of her son, Emmett Till. She is comforted by Gene Mobley, whom she would later marry. Photo by David Jackson

His killing galvanized the civil rights movement and opened the eyes of people to injustices, she said. “His death was the opening of the gates.”

When I telephoned Bryant, he expressed surprise at the city of Chicago for naming a street after Till. When I asked him for a sit-down interview, he demanded cash. I refused.

Double jeopardy bars retrial after acquittal, but the killers had never been tried for kidnapping.

That meant the killers could be charged with kidnapping. But when I reached out to a legal expert, he told me that Mississippi’s kidnapping statute at the time carried only a two-year statute of limitations, barring any such prosecution.

This has been the story of the pursuit of justice in this case: a few rays of hope, followed by disappointment.

***

In 2004, the FBI reopened the Till case after meeting with his cousin, Simeon Wright, Keith Beauchamp, the director of the documentary, The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till, and Alvin Sykes, who inspired the Emmett Till Cold Case Investigations Program.

By this time, Bryant and Milam had both died of cancer. (Donham, the only living suspect, is now 87 and reported to be in poor health.)

The FBI assigned agent Dale Killinger to the case, and he dove deep into the case, finding a trial transcript and new evidence, including the possible murder weapon, previously unknown witnesses and an autopsy that confirmed Till was killed by gunshot (disproving the ridiculous defense claim that the body wasn’t Till’s).

Killinger interviewed Donham, who repeated the lie and even augmented it, saying Till had “accosted” her and that “as soon as he touched me I started screaming for (Milam’s wife) Juanita.”

Donham also told Killinger that she didn’t initially tell her husband, Roy, what had happened because she feared what he might do to Till. After he did find out, she said he “asked me didn’t I have something I wanted to tell him and I told him no … he was really mad at me.”

That remark conflicts with her original statement that she told Roy as soon as he arrived back home.

Donham denied she went to Moses Wright’s home with her husband, Roy Bryant, and Milam.

Wright testified he heard a light voice identify Till as the one. Wright’s son, Simeon, told me his father later told him it was a woman’s voice.

A different witness told Killinger that he, too, had been picked up by Milam and Bryant that night and that Donham had told them he wasn’t the one. The witness said he was tossed out of the truck, suffering broken teeth as a result.

Donham told Killinger that Milam and Bryant had brought Till to her at the store. Although she recognized Till, she said she told them that he wasn’t the one. The men left with Till, and she didn’t see her husband until much later.

In 2007, a majority-black grand jury in the Mississippi Delta decided against indicting Donham on manslaughter charges.

But what the grand jury failed to hear was Donham’s original statement to her husband’s lawyer — a statement contained in the William Bradford Huie papers.

In 2017, Tyson published his book, The Blood of Emmett Till, which said that Donham’s memoir “recounts the story she told at the trial using imagery from the classic Southern racist horror movie of the ‘Black Beast’ rapist. But about her testimony that Till had grabbed her around the waist and uttered obscenities, she now told me, ‘That part’s not true.’”

That bombshell revelation shot the book onto The New York Times Bestseller List. Ads in The Hollywood Reporter offered the film and television rights for sale.

This ad ran in The Hollywood Reporter, offering the film and television rights of the book, The Blood of Emmett Till.

In response to public outrage, the FBI began to investigate the case again.

Tyson’s claim that Donham had supposedly recanted surprised me since he had told me she had stuck to her story. A year later, I heard that Donham’s family was denying that she recanted.

When I reached her daughter-in-law, Marsha Bryant, she said Tyson had interviewed Donham for the purpose of helping her edit and publish her memoir, More Than a Wolf Whistle: The Story of Carolyn Bryant Donham.

Tyson called Bryant’s claim that he was editor of the book “bullsh--.”

Bryant told me that she had been present during the entire time that Tyson spoke with Donham and that she had never heard the words that Tyson quoted. They weren’t in the tape transcripts either, she said.

When I reached Tyson, he confirmed the quote wasn’t on tape, insisting he was setting up the recorder at the time.

Are you kidding me? If someone delivered that kind of bombshell, I’d get them to talk about it again on tape. And I’d have other questions, too.

Tyson said when Donham began to mutter something about “they’re all dead now anyway,” he snatched up his notebook and began taking notes.

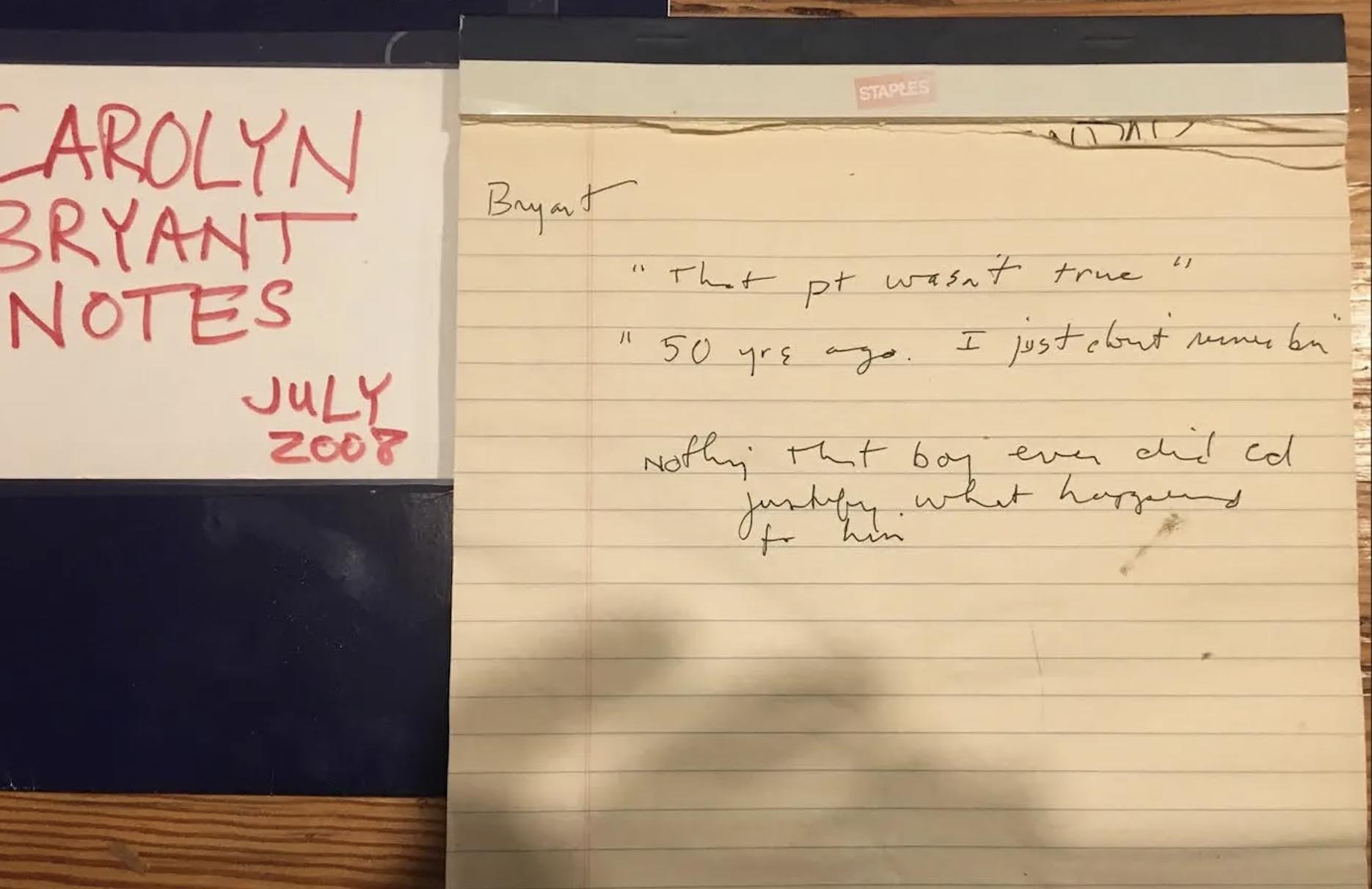

He then shared a photo of the handwritten notes, which read, “That pt wasn’t true. … 50 yrs ago. I just don’t remember. … Nothing that boy ever did could justify what happened to him.”

Those notes were translated into these words in the book: “Honestly, I just don’t remember. It was 50 years ago. You tell these stories for so long that they seem true, but that part is not true. … Nothing that boy ever did could justify what happened to him.”

When he shared his handwritten notes with me, my heart sank. These are his only notes? You land one of the most coveted interviews in recent history and you write down less than a few dozen words? Really?

Even when I tape interviews, I take extensive notes. I scribble down the date, the correct spellings of names and as many details as I can gather from looks to clothing to gestures.

Author Tim Tyson shared these notes with me as proof that he wrote down the bombshell quote he attributed to Carolyn Bryant Donham. She and her family have denied that she ever recanted.

Bryant said the family knew nothing about Tyson’s book until it was released, but Tyson said he told the family years ago he might do a book.

He said the family took no exception to the facts in the book, only the media scrutiny that resulted, but emails from Bryant show she asked Tyson why people were quoting him as saying Donham had lied.

On Monday, the Justice Department made public that it had closed the Till case without any charges.

“Today is a day that we’ll never forget,” Till’s cousin, Parker, said at a press conference. “For 66 years, we have suffered pain for his loss, and I suffered tremendously because of the way that they painted him.”

In its report closing the case, the Justice Department concluded there were “numerous inconsistencies” in what Tyson said.

His book’s first footnote says the bombshell quote came from a Sept. 8, 2008, interview, but he told me he had gotten the quote in July 2008.

He told investigators that the two 2008 interviews “kind of blur together” and that the footnote was in error.

Even more bizarre, he once published a different version online of Donham’s purported bombshell quote.

The date he gave for that quote? 2010.

He told investigators that was a mistake, too.

Asked how he knew what Donham was referring to when she said “that part wasn’t true,” Tyson said if the connection was not in his notes, “then he must have other written notes,” the report said. “Tyson, however, has not identified or provided investigators with any additional notes.”

What Tyson’s assistant told investigators is even more puzzling. “She recalled hearing the confessional comments in the first recorded interview while transcribing the statements,” according to the report. “She later told investigators she heard them in the recording of the second interview. In any event, after claiming to have heard the statements in one of the recordings, she had no explanation for why they are not included in either of her transcriptions.”

Tyson could only provide investigators with one of the taped interviews, but did have transcripts of the two interviews.

Asked why he didn’t get Donham to repeat her bombshell statement, Tyson told investigators that he “did not want to interrupt the flow of conversation,” the report said. “At other points in his interviews …, however, he asked her to repeat something or clarify her account. Tyson later told investigators that it was not until well after the interviews that he realized he did not have her recantation on tape.”

Wait a minute. Tyson told me he didn’t have his recorder set up. Isn’t this why he took the notes in the first place? And if he didn’t realize that until later, why would he have taken the notes to start with? There were no other notes.

After Tyson claimed Donham recanted, she continued to make statements consistent with her 1955 testimony, but Tyson “failed to challenge” her, the report said. “Moreover, the recording does not reflect that Tyson expressed surprise at this account or that he asked questions about why (Donham) was giving a different version of events than what she had told him previously.”

When investigators asked Tyson why he never reported Donham’s statement to authorities, he “explained that he did not consider her recantation to be particularly significant because he never credited her testimony in the first place,” the report said. “Tyson admitted, however, that (Donham’s) reported recantation was significant in marketing his book.”

In his book, Tyson wrote that Donham handed him a copy of both the 1955 trial transcript and the memoir she wrote. He promised to deliver both documents to “the appropriate archive, where future scholars would be able to use them.”

He placed her memoir in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill library archives, but investigators found no trial transcript there.

When FBI agents interviewed Tyson, “rather than obtaining other corroborating evidence to support Tyson’s claim that (Donham) offered a recantation,” the report said, “investigators instead identified numerous inconsistencies in Tyson’s account that raised questions about the credibility of his account of the interviews.”

Tyson has defended his actions, telling The New York Times that he took detailed notes: “Carolyn started spilling the beans before I got the recorder going. I documented her words carefully. My reporting is rock solid.”

In an email, Marsha Bryant disputed Tyson’s words: “Why would she ‘spill the beans’ to a stranger when she won’t even talk about it to family????”

Jerry Mitchell is the founder of the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting and the author of Race Against Time, which tells the stories of courageous families continuing to pursue justice for their loved ones in some of the nation’s most notorious racial killings.

The Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting is a nonprofit news organization that seeks to inform, educate and empower Mississippians in their communities through the use of investigative journalism.

Sign up for our newsletter.