Payback for Pain and Loss: Reparations for Relatives of Lynching Victims?

In the U.S., reparations have had a rocky, uneven history. After World War II, in which American Indians served in great numbers and in key roles, Congress approved financial compensation of about $1.3 billion for 178 tribes. But much of it ended up in government-controlled trusts. In the West, Latinos were lynched and present-day Latinos want attention paid. The Carter administration compensated Japanese Americans who were interned in camps during World War II, but the monies went only to living internees, with nothing for surviving relatives of deceased internees.

What about Black victims of lynching during Jim Crow? They are memorialized in Montgomery, Alabama, at the National Museum for Peace and Justice and at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum. Between 1882 and 1968, Mississippians lynched more Blacks than citizens of any other state.

Black victims of lynching during Jim Crow are memorialized at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, as well as the National Museum for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Between 1882 and 1968, Mississippians lynched more Blacks than citizens of any other state.

Some families of those Black victims are asking for more than memorialization. Specifically, they want reparations. Last week, the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project at Northeastern University School of Law held a conference on Lynching: Reparations as Restorative Justice.

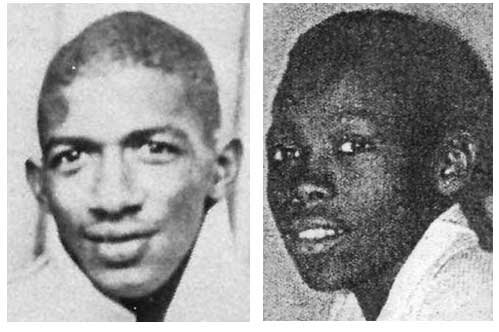

Among the voices heard were relatives or descendants of lynching victims. Thomas Moore described the death of his older brother, Charles “Eddie” Moore, a student at historically Black Alcorn University, who was abducted in the summer of 1964 while hitchhiking near Meadville, Mississippi. Members of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan tortured him and fellow hitchhiker Hezekiah Dee on suspicion of their belonging to a Black militant group smuggling guns into the state. Eventually the pair were tossed into the Mississippi River. Although the teens’ bodies were recovered amidst the search for the bodies of three young civil rights workers near Philadelphia, the case received scant attention. Thomas Moore explained, “We was nobody.” Then-district attorney of Franklin County dismissed the case.

(Thanks to the work of Moore and journalist David Ridgen, federal authorities reopened the case in 2005, and Klansman James Ford Seale went to prison two years later.)

Sheila Moss Brown is the granddaughter of Henry “Peg” Gilbert, a prosperous Georgia farmer lynched in 1947. Brown was the youngest of several children, and only 5 years old when her maternal grandfather died. She remembers her mother’s and older brothers’ grief and depression and worked hard to distract them and make them laugh. Most of the family never was able to overcome the loss. Brown herself has had the benefit of psychiatric care.

Charles “Eddie” Moore and Hezekiah Dee were abducted in the summer of 1964 while near Meadville, Mississippi. Members of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan tortured and killed them.

Because many lynchings like Gilbert’s were carried out to steal land or prosperous businesses, relatives want financial compensation. They do have support. In 2017, U.S. Rep. John Conyers Jr., D-Mich., reintroduced HR 40, which in its original version in 1989 called for a study of the possibility of reparations. Now it calls for reparations.

But what kind of chance do the families have? The Civil Rights and Restorative Justice director is Margaret Burnham, daughter of Louis E. Burnham, an activist and journalist during Jim Crow who wrote about Emmett Till’s lynching. At the conference, she said that “every reparation initiative builds” momentum, and that her organization plans to “help families organize their campaign” for reparations.

The most recent example of reparations is not encouraging. Professor Paul Watanabe, whose family was interned, closed the conference by reporting that during the Carter administration, families of the more than 100,000 Japanese Americans who were interned during World War II, asked for reparations. Eventually reparations were whittled down to a scant $20,000 per survivor, and awarded only to living citizens who had been interned. The total cost of these reparations for 82,000 living survivors came to $6 billion in federal funds.

Ann Marie Cunningham is a Columbia University Lipman Fellow for 2020 who will be working with the Mississippi Center for investigative Reporting. She is a veteran journalist/producer and author of a best-seller. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Technology Review, The Nation and The New Republic. Contact her at amclissf@gmail.com.