The Art of War: Has the Time Come for Johnny Reb to Stand Down?

While covering the 1962 riots at the University of Mississippi over James Meredith’s enrollment, Philippe Guihard, a warm, friendly French journalist, became the only reporter killed during the civil rights era. He was shot in the back from a foot away. The FBI lists his murder as unsolved. Before he died, Guihard wrote in his last dispatch, “The Civil War never ended.”

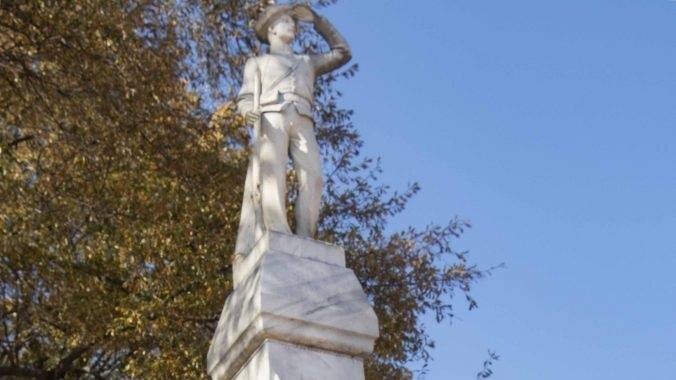

Guihard’s observation comes to mind in any of Mississippi’s cities and towns with courthouse squares where statues of Confederate soldiers stand guard. These sentinel statues face north toward the advancing Union Army or south toward home. Jackson filmmaker Philip Scarborough, who says he’s descended from at least five Confederate soldiers, has made a short film, Dear Johnny Reb, starring the statues. Using words from Mississippi’s Civil Rights Museum, Scarborough composed a letter to the statues and asked 42 other Mississippians to join him in standing in front of them and reading his letter.

The Mississippi Department of Archives and History approved plan to relocate the Confederate monument at the University of Mississippi mpbonline

Gen. Robert E. Lee is not in Scarborough’s film, although the general became the Confederate most frequently memorialized in metal and stone. Lee had written to a friend that he wanted no Confederate monuments, fearing they would keep division alive. Scarborough agrees: All the sentinel statues should come down. He feels “people go to courthouses to seek justice, and [sentinels] don’t belong on a courthouse lawn. These men actively fought against the Union.”

If the sentinels do remain at their posts, Scarborough believes each one needs a plaque that provides context.

In November 2020, the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project at Northeastern University School of Law held a conference on Lynching: Reparations as Restorative Justice. The conference opened with presentations by two artists who want to help clarify Black history. Quanda Johnson is a scholar and a stage performer whose work, she writes, disrupts “cultural archetypes about Blackness (The Angry Black Woman/Man…)” Dread Scott also presents performances, most notably his 2019 reenactment of the largest slave rebellion, which took place upriver from New Orleans in 1811.

Two weeks after the Northeastern conference, the idea of using art as a means of reconciliation had passionate support at a discussion organized by the Emmett Till Interpretive Center in Sumner, Mississippi. One participant, scholar Susan Neiman, writes in her 2019 book, Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil, that probably only a survivor can understand the pain of the Holocaust, and only a Black mother can understand “the pain of Emmett Till’s mother — or Eric Garner’s, Trayvon Martin’s, Tamir Rice’s.” But, Neiman continues, if you are neither, “you can get quite a lot, actually, if you let yourself be touched by a piece of art … The arts are the only thing that have the power to shake you up.”

Neiman spent some time as a scholar in residence at the University of Mississippi, which was in the midst of considering plaques to contextualize its campus’ Confederate monuments. She asked one member of the committee, Chuck Ross, a Black professor of African-American history, how different his life would be if he’d wound up teaching Black history in Ohio.

Ross replied, “Oh, it wouldn’t be as exciting. Here history is a living, breathing thing...You have an opportunity to live it.”

Gen. Lee summed up his wartime memories like this: “It is good that war is so horrible — or we might grow to like it.” One of his descendants told Susan Neiman, “Robert E. Lee himself said, ‘Furl the flag, boys, take it down.’” Ken Burns’ documentary series, The Civil War, makes clear that Lee remembered huge losses, on the same scale as World War I: 2 percent of the U.S. population died. Perhaps Mississippi’s sentinel statues can stand and serve as art that reminds us that regardless of why we go to war, it’s always hell. It is well that war is so terrible -- lest we should grow too fond of it.

Ann Marie Cunningham is a Columbia University Lipman Fellow for 2020 who will be working with the Mississippi Center for investigative Reporting. She is a veteran journalist/producer and author of a best-seller. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Technology Review, The Nation and The New Republic. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.