Another Cold War: Documenting America’s Cold Civil War

Last week, I mentioned French journalist Paul Guilhard’s last dispatch before he was killed at Ole Miss in the fall 1962 riots over James Meredith’s admission to the university. Almost a century after the official end of the American Civil War, Guilhard wrote, “The Civil War never came to an end.”

Almost 60 years after Guilard’s last dispatch, there is plenty of evidence the Civil War is still being waged. In fact, journalist and author Connor Towne O’Neill calls it America’s “cold” Civil War.

Barbara J. Fields was the first Black woman professor to earn tenure at Columbia University. A professor of American history, especially of the American South, she agrees with Guilhard and O’Neill that “the Civil War is still going on.” She goes a step further: She says, “It is still to be fought and, regrettably, to lose.”

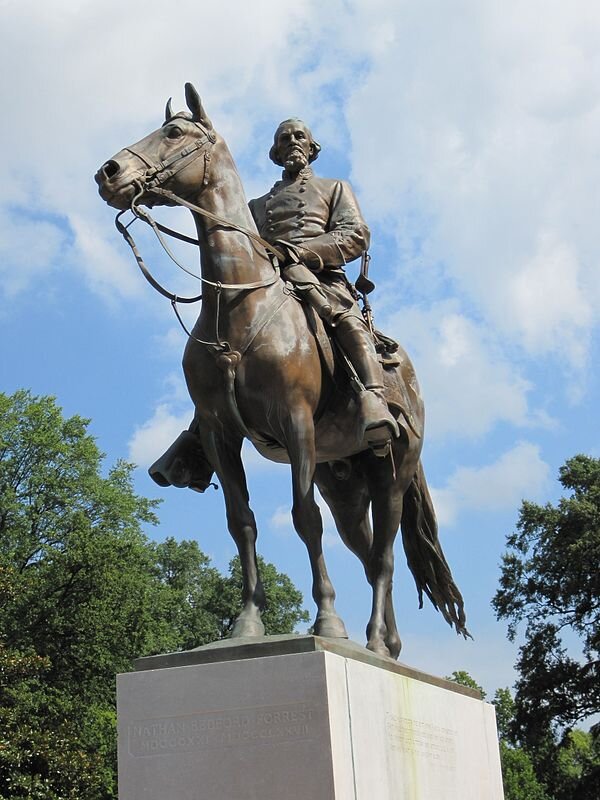

In a 2020 book, Down Along with That Devil’s Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments, Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy, O’Neill documents the cold Civil War by following battles over monuments to Confederate Gen. Nathan Beford Forrest given to the fictional character Forrest Gump and to streets and counties all over the South, but especially in Forrest’s native Tennessee. There are controversial monuments to him in Memphis and Nashville, and despite protests, his name remains on Forrest Hall at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro.

Forrest is not just any Confederate general; even during the Civil War, he was notorious. Towards his own soldiers, Forrest was pitiless and cruel. At Fort Pillow, now a state historic park in western Tennessee, he ordered a massacre of more than 300 Union soldiers, including 200 Black soldiers, who were trying to surrender. Union general William Tecumseh Sherman called Forrest “the very devil.”

The statue of Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest is seen here in its former location in Health Sciences Park (then called Forrest Park) in Memphis, Tennessee, in 2010. Wikipedia

Before the war, Forrest became one of the richest men in Tennessee as a slave trader and planter. After the war, he probably accepted an invitation to become the overall head of the new Ku Klux Klan, the first Grand Wizard. Towards the end of his life, Forrest supposedly repudiated the Klan, perhaps because of a near-deathbed embrace of Christianity, perhaps because he considered the Klan too disorganized to be effective.

O’Neill’s book quotes a protestor at Middle Tennessee State who is fighting to change Forrest Hall’s name: “How can we begin to dismantle White supremacy when we can’t even take down its symbols?... If it’s this hard to take down a symbol from the past for a war that’s lost, if it’s that hard, we got work to do.” As long as those symbols are up, they are “like a flag in a war.”

After Dylann Roof attempted to start a race war by murdering nine people at prayer in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, attacks on Confederate monuments intensified. By early 2017, campaigns to remove them had heated up. In New Orleans, when Gen. Robert E. Lee’s statue was removed from Lee Circle, Mayor Mitch Landrieu delivered a scathing speech that O’Neill quotes: “These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictionalized, sanitized Confederacy, ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for.” Removing them was “making straight what was crooked, making right what was wrong.”

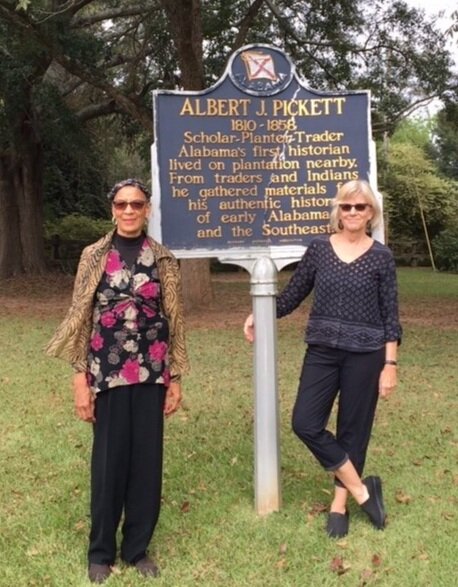

About the same time, New York-based journalist Ann Banks decided to retrieve from deep inside her office closet a foot-high pile of papers left to her by her father from his Alabama relatives. Banks knew she was a direct descendent of Alfred J. Pickett, planter and cousin to Gen. George Pickett of Pickett’s ill-fated Charge at Gettysburg and other prominent Confederates. She never had wanted to explore her ancestry. “For a long while I believed the Civil War was over,” she writes in an introductory essay on her website, Confederates in my Closet.

The great-grandfather of Karen Orozco Gutierrez, left, was enslaved at this plantation owned by the great-great-grandfather of Ann Banks, right. Click here for their story. Courtesy Ann Banks

“There are many kinds of not knowing,” Banks goes on. “There is knowing and then forgetting. There is knowing but failing to imagine. And then there is just looking away. These were all ways I did not know the stories that make up my paternal family history, populated with slaveholders and Confederate generals.”

Banks discovered that Pickett’s much younger widow, LaSalle Corbell Pickett, had spearheaded the movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to put up Confederate monuments and portray the Civil War as the South’s romantic Lost Cause. On her website, Banks documents how LaSalle Pickett went so far as to ghostwrite a book that she published as the general’s letters to her from the field.

I was horrified to learn that these fake letters were used as source material in Michael Schaara’s novel about Gettysburg, The Killer Angels, which won the 1975 Pulitzer Prize; Mississippi writer Shelby Foote’s three-volume history of the Civil War; and documentary producer Ken Burns’ series on the Civil War, which still is used in schools. Banks says that at the site of Pickett’s charge on the Gettysburg battlefield, there is a bench with a quote from Schaara’s novel.

As O’Neill wrote about the myth of the Lost Cause, “Same war. Different generals.”

Banks has dealt with her ancestry in an exemplary way. She and Karen Orozco Gutierrez, whose great-grandfather was enslaved by Banks’ great-great-grandfather, traveled together to Montgomery, Alabama, to research their shared history. They visited the site of Alfred J. Pickett’s plantation and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, informally known as the lynching museum.

Virginia’s Camp Pickett, like nine other Army bases named for Confederate generals, will be renamed. Banks is glad, and she agrees with another Pickett descendent, a surfing instructor who believes that all Confederate monuments should become artificial coral reefs, or displayed on the battlefields.

Ann Marie Cunningham is a Columbia University Lipman Fellow for 2020 who will be working with the Mississippi Center for investigative Reporting. She is a veteran journalist/producer and author of a best-seller. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Technology Review, The Nation and The New Republic. Contact her at amc@mississippicir.org.